P ioneers in the Asian art world, Tuyet Nguyet (1934-2020) and Stephen Markbreiter (1921-2014) were the founders of Arts of Asia, the premier magazine for Asian art and antiques. Nguyet began her career a dynamic journalist hailing from Vietnam and Stephen Markbreiter was a distinguished English architect. Together they shared a love of Chinese and Asian art, and over the years formed impressive collections of Chinese art.

Presented here in this sale, the gathered works reflect the extensive journey across Asia taken by two passionate and dedicated collectors, in a celebration of the spectacular creative vision and skill of artisans working throughout the continent.

“With over five decades of experience, my parents had amazing knowledge, and amassed a vast collection of Asian art.”

The Mystery of Archaic Jade Forms

Archaic ritual jades are the perfect harmony of form and decoration, representing the interaction between art and ritual in a narrative that predates the written word. While the exact meanings have obscured through the passage of time, offering a tantalizing glimpse of bygone Neolothical jade cultures, they remain a source of fascination for millennia. The design and motifs hint at ancient religious or spiritual beliefs, and such clues have attracted much speculation. While the function and meaning remained shrouded in mystery, many of the symbols and motifs have persisted, marking the development of principal jade forms, which have been adapted in later dynasties.

Among the most enigmatic object is the cong, hollowed-out cylinders that are round on the inside and square on the outside. The Neolithic form was given the name cong during later dynasties, and the combination of circle within the square was interpreted as a symbol of earth. These archaic jade forms inspired connoisseurs from as early as the Song dynasty through to the present, some imitated for their aesthetic qualities while others collected as ancient curiosities. The collared disc is another form with Neolithic origins, many unearthed from early tombs. Many such discs are plain without engraving and the stonework tends to be simple. The shape resembles a spinning ring and was primarily associated with female burials for the very wealthy. The form was later interpreted as a symbol of heaven and hence became one of the most important design elements in Chinese history. Motifs such as centipedes and cicadas were also powerful symbols and may have had special functions in burial rites. For example, jade cicadas are emblems of immortality, often presented as burial objects, thought to be placed on the tongue as the final honour to the entombed.

For thousands of years stretching back to the days of prehistoric cave paintings, our art has taken as subject matter flora and fauna of all kinds. The artist’s fascination with animals has expressed itself in stories and dreams — as deities and demons, fables and fantasies, loyal companions and wild enemies. Animals in Chinese art have long been a way of conveying philosophical and sometimes political meaning in a sophisticated visual language of cultural associations and wordplay. Depictions of animals cannot be construed as superficial or merely decorative. Real and mythical animals had spiritual meanings bound to individual motifs, and they were assigned specific places within in the universe in accord with Chinese cosmology.

Click on the hotspots below to read more.

- Victoria Peak Then and Now

View From Victoria Harbour. Photo by Joey Cheung. Source: Shutterstock.

ShutterstockVictoria Peak had been a towering presence looming far above the low-rise buildings clustered at its feet. Today you can barely see the peaks through the space between the densely packed skyscrapers and high-rises.

- Western Artists that Settled in China

George Chinnery by George Chinnery Many of the earliest painters of these China trade art were Western artists, notable George Chinnery. Chinese artist later began their own studios, employing these new painting techniques with its particular visual repertoire in their depictions of city ports, daily life and mutual cultural exchanges. These works were created as souvenirs for tradesmen who had embarked on long trips from Europe. Because of the particular moment at which these paintings were created, they are not only works of art but also important historic documents.

- A Fledgling Colony

On 26 January 1841, Chinese ceded Hong Kong Island to the British following the end of the First Opium War. The British took possession of Hong Kong at Possession Point. The town they built was named Victoria City, and in two decades the population of the fledgling colony had already grown to 125,504 according to an official government guide for “for travellers, merchants, and residents in general”.

- The Evolving Hong Kong Skyline

High upon the hill is St. John's Cathedral, the oldest neo-gothic cathedral in East Asia that still stands in Central today. At the time of the painting, it was the tallest structure in Hong Kong. Much of the landscape would change dramatically beginning the 20th century, as commercial buildings and the later wave after wave of skyscrapers began to emerge, overtaking the older three-storey trading houses dotted along the waterfront as they look out onto Victoria Harbour.

- Port Scenes in China Trade Paintings

Hong Kong was declared a free port by the Superintendent of Trade on 7 June 1841, and a general invitation to merchants to trade was extended. Despite this, the first couple of decades showed disappointing development of shipping and trade, owing to the rampant piracy, illegal opium trade, and competition from other treaty ports. After the 1860s, Hong Kong saw a boom in shipping buoyed by the growing population and trade with other European nations.

- The Development of Trade

The foreign factories, or hongs, were the catalyst for the rapid development of trade and economic prosperity along waterfront. The present example depicts the waterfront during this time of affluence and growth, as evident by the busy waterways. Below is a portrait of Howqua, a hong merchant and leader of a the powerful guild of thirteen Chinese traders authorized by the Chinese government to oversee dealings with the West. In 1834 Howqua possessed a personal wealth estimated at $26 million, a mighty fortune that made him one of the wealthiest men in the world at the time.

English artist George Chinnery was unusual in that he was one of the earliest European painters to take residence in southern China in the mid-19th century, bearing witness to the height of the China Trade before the outbreak of the first Opium War. He arrived in Macau in 1825 from Calcutta, after having already established himself as the leading Western artist in India. His remarkable oil paintings, sketches, and watercolours captured the port scenes, portraits, and interiors of Hong Kong and Macau, before the arrival of photography to the China coast, and exerted a powerful force on export portraiture. The expatriate English artist would have a significant stylistic influence on the likes of Lamqua, the most notable Chinese export artist who worked for the Western market.

- George Chinnery (1774-1852)

- Portrait commissions

- Local landscapes

- Everyday activities

- Macau/Canton Period, 1825-1852

- Macau landscape

- Chinese Junks

- Sampan girl series

- Chinnery and his followers

- Lamqua (fl. 1820-1860)

- Becoming export goods

- Games and drinking scenes

- Portraits of scholars

- Portraits of ladies

- Connection with Hong Kong – Sir Paul Catchick Chater (1846-1926)

-

George Chinnery an English portrait and landscape painter, notable for having been one of the earliest most prominent 19th century European artists to live in South China prior to the arrival of photography. Before embarking for Asia. He trained at London’s Royal Academy Schools, as a contemporary of Joseph Mallord William Turner. In 1791, at the age of 17, Chinnery established himself as a miniature painter and exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy.

-

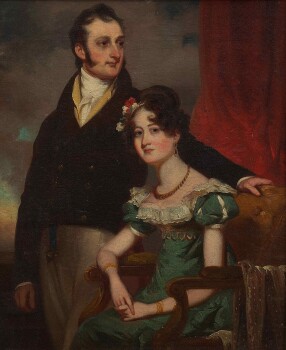

In 1802, Chinnery received permission from the East India company to travel from England to India, where he worked as a painter and gradually received more prestigious portrait commissions. An example is his 1820 Portrait of a Lady and Gentleman. By 1812, he was established in Calcutta as one of the preeminent Western artists in the capital of India.

In 1802, Chinnery received permission from the East India company to travel from England to India, where he worked as a painter and gradually received more prestigious portrait commissions. An example is his 1820 Portrait of a Lady and Gentleman. By 1812, he was established in Calcutta as one of the preeminent Western artists in the capital of India.

VIEW LOT -

His works mainly revolved around official portraits, but gradually he began to depict landscapes, fascinated by local daily life and social interactions, as well as a broader view on culture, all of which he saw for the first time. Movements of figures and animals, drawing different specimens of trees, grasses and rocks, were where his skills and experience as a top-ranking draughtsman developed. He further studied with watercolour the new expression of light and reflection in water surfaces.

His works mainly revolved around official portraits, but gradually he began to depict landscapes, fascinated by local daily life and social interactions, as well as a broader view on culture, all of which he saw for the first time. Movements of figures and animals, drawing different specimens of trees, grasses and rocks, were where his skills and experience as a top-ranking draughtsman developed. He further studied with watercolour the new expression of light and reflection in water surfaces.

VIEW LOT -

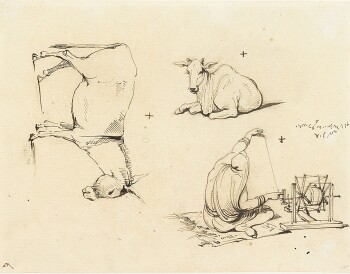

While in India he made many sketches in pencil of local life, people engaged in their everyday activities and painted scenes of local architecture in watercolour. A beautiful example of this is Two Sketches of Indian Woman Spinning. In this work, Chinnery even wrote in shorthand recording the method by which Indian women would spin. The shorthand inscription reads: "The string ought to be drawn quite tight. The machine ought to be rather nearer to the woman".

While in India he made many sketches in pencil of local life, people engaged in their everyday activities and painted scenes of local architecture in watercolour. A beautiful example of this is Two Sketches of Indian Woman Spinning. In this work, Chinnery even wrote in shorthand recording the method by which Indian women would spin. The shorthand inscription reads: "The string ought to be drawn quite tight. The machine ought to be rather nearer to the woman".

VIEW LOT -

After spending 23 years in India, he sailed for China in 1825. He was based in the Portuguese enclave of Macau, which was to be his home for the rest of his life, interspersed by frequent visits to Canton (modern Guangzhou), Whampoa, and Hong Kong.

This period in the Far East is his golden age as an expressionist painter. His sketches and brushwork grew rapidly freer and more refined. His works became small in scale depicting extreme simplification of his ideas. -

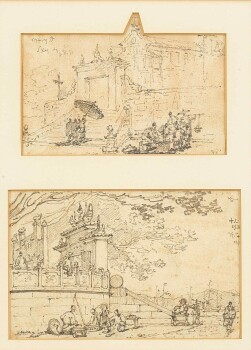

Chinnery spent much of his time in Macau observing and painting the landscape and life around him, sketching in pencil and working up watercolours and oils in his studio. His skill is showcased in Two Sketches of Macau (depicting Ruins of St. Paul's & A-Ma Temple). These paintings were typically created on a small scale, perhaps because of the fashion at the time favouring paintings that could fit the small rooms of the houses in Macau.

Chinnery spent much of his time in Macau observing and painting the landscape and life around him, sketching in pencil and working up watercolours and oils in his studio. His skill is showcased in Two Sketches of Macau (depicting Ruins of St. Paul's & A-Ma Temple). These paintings were typically created on a small scale, perhaps because of the fashion at the time favouring paintings that could fit the small rooms of the houses in Macau.

VIEW LOT -

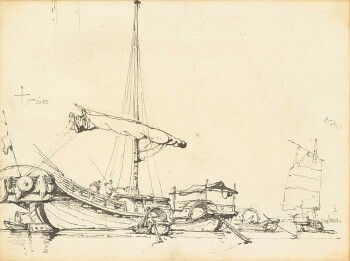

Chinnery has also left behind many watercolors and drawings that sketched the landscapes of Guangdong, Macau, Hong Kong and the Chinese living there. By the time he created this sketch, Chinese Junks at Anchor, he had already made a name for himself as "the most famous Western painter in East Asia".

Chinnery has also left behind many watercolors and drawings that sketched the landscapes of Guangdong, Macau, Hong Kong and the Chinese living there. By the time he created this sketch, Chinese Junks at Anchor, he had already made a name for himself as "the most famous Western painter in East Asia".

VIEW LOT -

By the 1840s Chinnery had already grown accustomed to his new home in the South China and deepened an exchange of relations with its people. From that decade, his portrait series of a Sampan girl, which included Study of a Chinese Girl, exudes that sense of a nostalgia.

By the 1840s Chinnery had already grown accustomed to his new home in the South China and deepened an exchange of relations with its people. From that decade, his portrait series of a Sampan girl, which included Study of a Chinese Girl, exudes that sense of a nostalgia.

VIEW LOT -

From the 1820s to Chinnery's last years in China in the 1850s, an artist community emerged around in George Chinnery, whose members were faithfully followers of his painting style and aesthetic.

-

The best know of the Chinese artists is Lamqua, who produced works under the guidance of Chinnery and successfully mastered his style. He later became independent, built his workshop in Canton after the 1830s, and in Hong Kong after 1845, and produced many works based on Chinnery’s skills and style. It is ironic that Chinnery’s beloved pupil became his greatest rival, gradually began taking his customers from him.

The best know of the Chinese artists is Lamqua, who produced works under the guidance of Chinnery and successfully mastered his style. He later became independent, built his workshop in Canton after the 1830s, and in Hong Kong after 1845, and produced many works based on Chinnery’s skills and style. It is ironic that Chinnery’s beloved pupil became his greatest rival, gradually began taking his customers from him.

VIEW LOT -

In the first half of the 19th century, demand for those chinoiserie works rose greatly, and paintings began to show a decorative beauty combined with Chinese original lacquer and word-carved frames. Like tea and silk, porcelain and furniture, these works were created for the express purpose of export made for the U.S. and England.

-

The most popular themes, for landscape paintings, were panoramic scenes depicting boats that sailed between the foreign firms of Guangzhou settlement and Zhujiang (Pearl Bay) or Hong Kong Island.

The most popular themes, for landscape paintings, were panoramic scenes depicting boats that sailed between the foreign firms of Guangzhou settlement and Zhujiang (Pearl Bay) or Hong Kong Island.

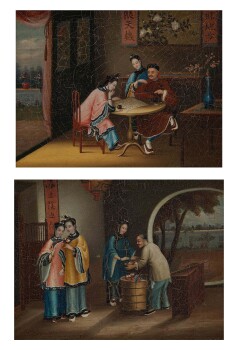

For genre paintings, were indoor scenes of people enjoying games and drinking. Charming examples include Gentleman and Ladies Playing Chess and Ladies Buying Flowers.

VIEW LOT -

Chinnery's output encompassed a wide range, and his influence on Chinese Trade Paintings is evident in the dramatic style of portraiture that he introduced, later adopted by Lamqua and other Cantonese artists that followed.

Chinnery's output encompassed a wide range, and his influence on Chinese Trade Paintings is evident in the dramatic style of portraiture that he introduced, later adopted by Lamqua and other Cantonese artists that followed.

VIEW LOT -

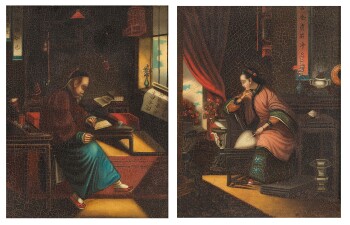

Many of the painting show interiors, from the variety of furniture arrangements within homes as well as the people engaged in everday life. These works were outside of the mainstream of the Chinese artistic tradition thematically and in media. Two Reclining Ladies on Day Bed are a pair of glass paintings depicting an intimate scene.

Many of the painting show interiors, from the variety of furniture arrangements within homes as well as the people engaged in everday life. These works were outside of the mainstream of the Chinese artistic tradition thematically and in media. Two Reclining Ladies on Day Bed are a pair of glass paintings depicting an intimate scene.

VIEW LOT -

James Orange is also a collector of Chinnery and bequeathed to the Victoria & Albert Museum eighteen works by Chinnery from his own collection. He wrote a number of works relating to Chinnery and his endeavours, including The Chater Collection: Pictures relating to China, Hongkong, Macao, 1655-1860 on the collection of his friend, the broker Sir Paul Catchick Chater (1846-1926).

James Orange is also a collector of Chinnery and bequeathed to the Victoria & Albert Museum eighteen works by Chinnery from his own collection. He wrote a number of works relating to Chinnery and his endeavours, including The Chater Collection: Pictures relating to China, Hongkong, Macao, 1655-1860 on the collection of his friend, the broker Sir Paul Catchick Chater (1846-1926).

The Chater collection is one of the most legendary collections, which originally contained more than 400 works of art. The artworks were displaced during the Japanese occupation during World War II, of which only around 80 pieces were returned to the government by local residents and organizations.

VIEW LOT