F rom the ancient Silk Road to the present-day Belt and Road, trade connections between China and the West have been an important part of global history. Towards the late 18th and early 19th centuries, all trade between China and the West passed through Canton, modern day Guangzhou. It was the main gateway for goods flowing in and out of China until the First Opium War between 1839 and 1842.

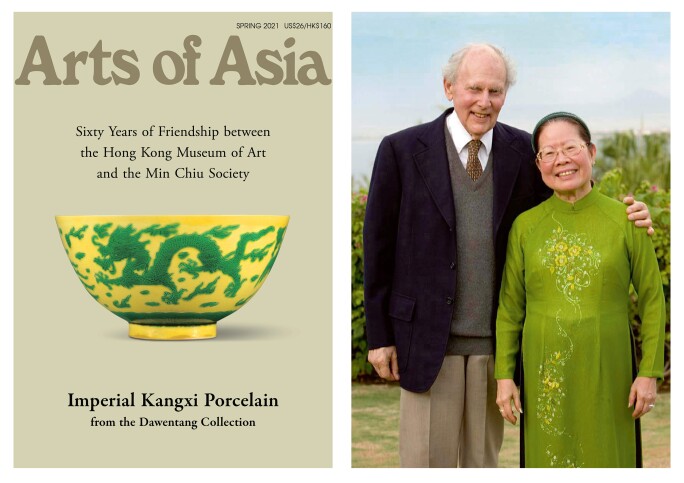

Art opens a vibrant window into the people and trade of the period, all of which has a place of prominence in A Connoisseur’s Eye: The Collection of Tuyet Nguyet And Stephen Markbreiter. The auction features a series of Chinese trade paintings from the collection of Tuyet Nguyet and Stephen Markbreiter, pioneers in the world of Asian art and founders of the Arts of Asia magazine.

While expansive in its range, the collection provides a focus into some of the most influential people in the region during the period, not just powerful merchants and patrons of the art like Howqua, perhaps the richest man in the world at the time, but also the most prominent early China-based artists including George Chinnery and his pupil Lamqua.

A Window into China’s History

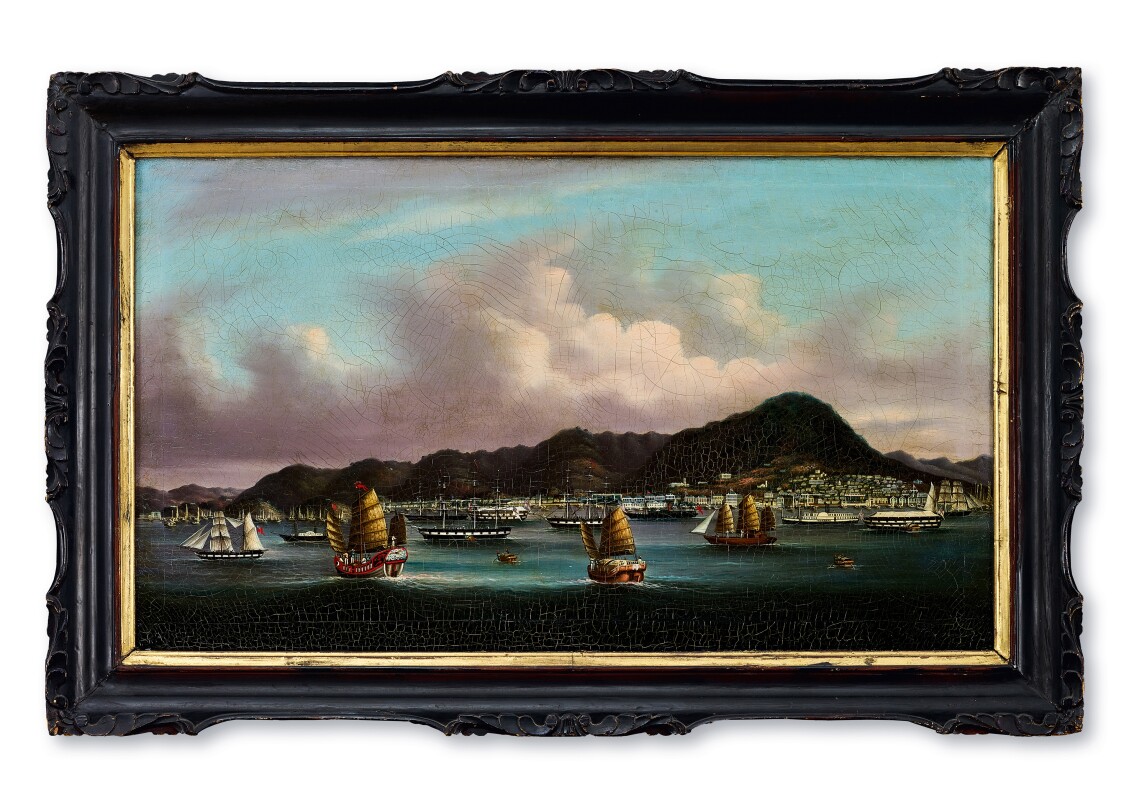

At the time just preceding the First Opium War, it was the fashion for Western merchants to have their portraits painted by Chinese artists and for Chinese merchants to give portraits of themselves to Western counterparts as souvenirs. Travellers would also commission works that would capture the hustle and bustle in Canton, bringing these port scenes back home to Europe or North America as souvenirs.

China trade paintings were created in Asia for export to the Western market. While such works have existed for centuries, the period between the 18th and 19th century saw a boom, producing the majority of existing works. This period coincided with a rapid increase in trade between China and the West, fuelled by the commercial expansion in southern China and the growth of Hong Kong.

The export paintings provide a fascinating record of this activity. Important examples from Nguyet and Markbreiter’s collection include portraits and bygone landscapes of Hong Kong, Macau and Canton; they capture life in vivid detail and track the evolution of history through Hong Kong’s humble beginnings as a fishing village through the glory days of the Canton System leading up to the First Opium War.

Portrait of the Wealthiest Man in the World

One of the highlights is an oil on canvas portrait of a distinguished Chinese man with kindly eyes seated in a regal navy robe, his gaze directed towards the onlooker. His face might look familiar to those who have seen a similar but fuller length portrait of the same subject titled A Chinese Merchant bequeathed by the architect and collector W. Gedney Beatty in 1941 that now hangs in the American Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The man in question is Howqua, the representative of the thirteen factories among the Guangzhou merchants. The subject of this portrait is probably Wu Bingjian (1769-1843), the richest man on earth during the Jiaqing and Daoguang periods, or possibly his fifth son, Wu Shaorong (1833-1856). Howqua Wu Bingjian, had risen to become the most senior of the hong merchants in Canton, one of a select few permitted to trade in silk and porcelain with foreigners. The word hong (行) refers to both a type of building and a Chinese merchant intermediary within the Canton system of trade.

Howqua’s personal wealth was estimated to be around US$26 million by 1834, an enormous fortune at the time. Legend has it that when a fire in 1822 destroyed the many cohong (公行), or business guild buildings in Canton from which he derived his wealth, the silver that melted formed a stream that extended more than three kilometres long.

Howqua was known as honest and generous in both his personal and professional dealings. He would offer assistance to foreign merchants that ended up “financially embarrassed” and, over time, invested in American railroads and other new technology of the time. He contributed a third of the US$3 million that China’s Qing dynasty was required to pay in reparations to the British after the 1842 Treaty of Nanking that ended the First Opium War.

Howqua had close ties with powerful contemporaries such as James Matheson, William Jardine, Samuel Russell and Abiel Abbot Low. When he died in 1843, he was honoured with tributes ranging from the naming of a clipper ship after him to a memorial poem and even a wax effigy at Madame Tussaud’s that was displayed for years in London.

Chinnery and Lamqua

Howqua has been immortalised through his portraits. While he appears in the small watercolour-on-ivory portrait that currently hangs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and that was done by the Chinese artist Tingqua (Guan Lianchang, 1809 –1870), his portraits are more frequently associated with the artist George Chinnery (1774–1852).

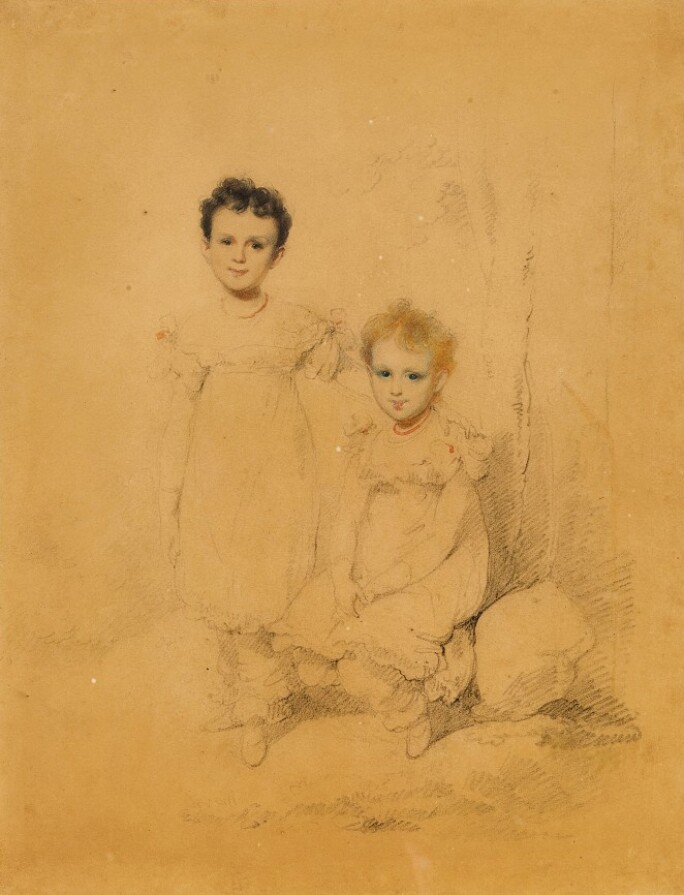

Chinnery’s own life was as vibrant as his paintings. He was born in London in 1774, the son of an amateur artist. By the time he was 17, he had exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts. From there, he continued working on portrait miniatures, small whole-lengths and portraits in oil and crayon or pencil, and finally watercolours and landscapes, until 1846.

In 1797, he moved to Dublin and had a family but he left them behind when he sailed for India in 1802. He stayed in India until 1825 when he sailed for Macau, presumably to escape both his creditors as well as his wife and family that had caught up with him in Calcutta (today’s Kolkata).

The first English painter to settle in China, Chinnery lived there until his death in 1852. He became fast friends with the American and British traders in Canton, who sought him out for both his portraits and lively wit. Chinnery set the style that his many pupils would follow in their own portraits of traders, merchants and historical figures, a style that would become widely influential.

Despite the many paintings he is thought to have done, there is only one painting of Howqua that Chinnery definitely created, currently in the possession of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC).

Chinnery’s portrait of Howqua, along with that of another merchant of the period known as Mouqua, was commissioned around 1827 by W. H. Chicheley Plowden, the president of the East India Company in Canton. Plowden is thought to have taken the portraits back to England with him in 1830. A shorthand notation by Chinnery in a preliminary drawing suggest the portrait dates back to 26 December 1827.

The portrait of Howqua that Sotheby’s will auction this month was created by Lamqua, a Chinese protégé of Chinnery and his eventual rival in business. Lamqua was among the artists that had been drawn into Chinnery’s orbit and faithfully followed his European painting style and aesthetic.

Lamqua, or Kwan Kiu Cheong, was the first Chinese portrait painter that was exhibited in the West and the most notable Chinese export artist in the Western market. He started out producing works under Chinnery’s guidance and successfully mastered his style.

He later struck out on his own, building a workshop in Canton in the 1830s and in Hong Kong after 1845. In a somewhat ironic twist, Lamqua’s mastery of Chinnery’s style allowed him to take work away from his former teacher.

Lamqua also became known for a series of medical portraits he painted between 1836 and 1855. Commissioned by the physician Peter Parker, a medical missionary from the United States, the series includes pre-operative portraits of patients with large tumours or other deformities.

A Lovingly Curated Collection

The works in ‘A Connoisseur’s Eye: The Collection of Tuyet Nguyet And Stephen Markbreiter’ feature much more than China Trade paintings. There is also a range of jade figures stretching from the Neolithic period all the way to the Qing Dynasty, the last dynasty in China that ruled between 1644 to 1912.

Nguyet (1934-2020) was a journalist from Vietnam while Markbreiter (1921-2014) was a distinguished English architect. The couple were considered pioneers in the Asian art world. They founded the Arts of Asia magazine in 1970, which has the largest circulation of any Asian arts magazine. The couple built an impressive collection of Chinese art, including the items in this auction.