Marcus David Ezekiel was born in Bombay in 1854, the son of David Hay Ezekiel. By 1875 he was in Shanghai, employed by E.D. Sassoon & Co. E. D. Sassoon was Sir Percival David’s maternal grandfather (Sir Percival’s full name was Percival Victor David Ezekiel David). In 1887 Marcus Ezekiel signed an Agreement of Association with E.D. Sassoon & Co., which was to last for four years. He became a Director of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, where he represented E.D. Sassoon & Co.

By 1900 Marcus Ezekiel had left China and settled in the Sussex seaside town of Hove, purchasing a house at 47 Tisbury Road, a substantial semi-detached house which must have been fairly recently constructed, built of the yellow brick characteristic of that town in the late 19th century. He married the daughter of Louis Behrens, she being the granddaughter of Charles Kensington Solomon, composer of synagogue and church music. They had one son, Victor Oscar David Ezekiel, born in 1905. Tisbury Road was to be Marcus Ezekiel’s home for the rest of his life.

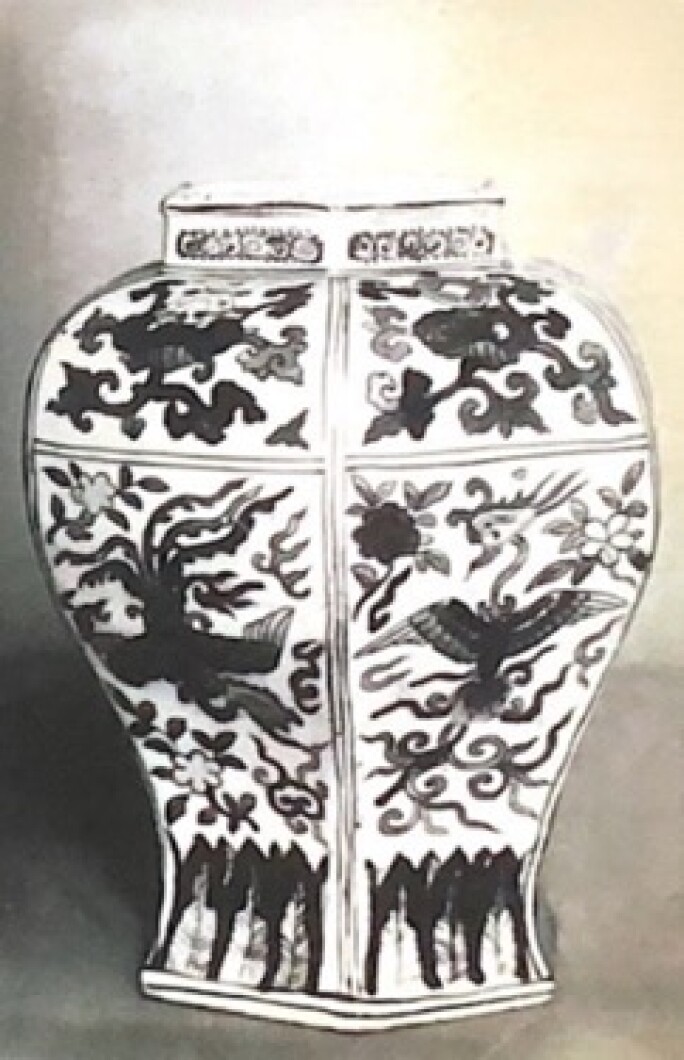

Marcus Ezekiel formed an extensive collection of Chinese art, mostly ceramics, but with a small group of Chinese glass and a cabinet of snuff bottles. At his death in 1927 this collection was left to his wife, effectively as a pension fund. In March 1930 she sold part of the collection at Christie’s 225 pieces, mostly Qing, for a little over £5,000. She sold a further group of 271 pieces at Sotheby’s in May 1946, including a group of good Song dynasty ceramics, for £4,750:10. This was a much more interesting sale than Christie’s of March 1930, and it may be that she was drawn by the reputation of Jim Kiddell to go to Sotheby’s. This sale included a good group of Song ceramics, a large group of porcelains decorated in underglaze blue of Ming and Qing dynasties, and a large number of monochrome porcelains, mostly of the Qing dynasty,

A certain amount of confusion has grown around the Ezekiel collection. In her book “Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain”, (Bern, 2007), Stacey Pierson states that his collection was given to the Hove Museum after his death (p. 107, referenced to The Times, May 24th 1927). Whilst Marcus Ezekiel was supportive of this institution in its formative years, he gave the Museum no more than a representative group of Chinese ceramics.

I had believed that Marcus Ezekiel had formed the bulk of his collection in China. The prevalence of this belief was brought home to me when, on a visit to the elderly John Ayers with a mutual friend a few years ago, I mentioned that I was working on the Ezekiel collection, and John Ayers remarked that he understood it had been put together in Hong Kong. Considering the pieces that were sold at auction, particularly those sold at Sotheby’s in 1946, it is clearly the collection of an intelligent and informed collector buying not in Asian but on the European market in the early 20th century, and subsequent and most unexpected discoveries were to prove this to be correct.

In 2015, the Oriental Ceramic Society was preparing for a major exhibition of Chinese Ceramics with loans from the Society’s members (“China Without Dragons”, 2016, held at Sotheby’s). Regina Krahl, then President of the Society, suggested that I might like to join her on a visit to David Ezekiel to select some pieces for the exhibition. David and Carolyn made us most welcome and thus began my research into the origins of the Ezekiel collection.

The family retains what turned out to be Marcus’s Collection book. A famous piece I knew from the collection was the Longqing mark and period wucai hexagonal vase, much published and now in the Avery Brundage Collection at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. It was clearly described as “1 Large F.V. vase Lungching Yamanaka” on the first page, for his 1922 purchases. The entry made it clear that Ezekiel has purchased this vase from the London branch of the international dealer Yamanaka & Co., then at 127 New Bond Street, on May 24th 1922, for £35.

I had already analysed Marcus Ezekiel’s purchases from Bluett made between 1916 and 1925, and by cross-referencing them with entries in the Student Exercise Book I could check the accuracy of these entries. This proved to be satisfactory and I could consider that the Book gave a reasonably accurate account of the development of Ezekiel’s collecting. The size of the collection by this account, set against the number of pieces sold and those retained by the family, although not a precise match, seemed close enough. According to the Student Exercise Book the total number of pieces in the collection was 697, The total number of pieces sold at auction (496), a few pieces sold through Bluett in 1921 (12), pieces given to museums (13) and pieces retained by the family (about 70), is about 590. This was a fairly large collection. David Ezekiel recalled his grandmother saying that it has been displayed in ten show cases at Tisbury Road, and photographs show many larger pieces on open shelves.

As Marcus Ezekiel was at some distance from the Chinese Art collectors in London, although only an hour or so away by train, one wonders what may have influenced him, or, perhaps, what his influence may have been. He had as a close neighbour a man who was described in his July 1937 obituary in the Sussex Daily News as “one of the best known collectors of Chinese Porcelain in the country, and had the honour two years ago of being one of the biggest individual contributors to the Chinese Exhibition held at Burlington House, 32 pieces of his collection being chosen for the occasion”. Captain Annesley Tyndal Warre (1861-1937) lived at 13 Salisbury Road, four streets away from Tisbury Road. By the time of his death his collection numbered 300-400 pieces. I find it hard to believe that they were not acquainted as they must have visited the same London dealers. In 2011 Christie’s had access to Captain Warre’s Collection Books, which had been retained by the Warre family. Purchase details were given for four of the lots included in their sale of May 10th 2011.

One of these was a small Kangxi mark and period yellow glazed cup with handles, brought from Yamanaka on March 11th 1914. Marcus Ezekiel made purchases from Yamanaka on March 6th, 18th and 27th 1914, the first of these being a small Kangxi period yellow-glazed cup.

Chinese glass was of particular interest to Marcus Ezekiel, he owned about twenty pieces, bought between 1908 and 1924. In this he may also have been influenced by (or perhaps may have influenced) Captain Warre, who had at least 39 pieces of Chinese glass in his collection, five of which were lent to five of which were lent to the 1935 Chinese Exhibition. All but four pieces of Captain Warre’ s glass were sold by Bluett to H.R. Burrows-Abbey in 1944-45 for £484:10, and are today in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery. Marcus Ezekiel had a small group of yellow monochrome glass vessels, three of which were sold at Sotheby’s May 1946 sale, but an unusual yellow glass bowl with reticulated decoration was kept, and lent by Marcus’ son, Victor Ezekiel, to the Oriental Ceramic Society’s exhibition “The Arts of the Ch’ing dynasty” in 1964.

© Royal Academy of Art, London

A type of Chinese glass that particularly appealed to Marcus Ezekiel were those pieces delicately painted in polychrome enamels on an opaque white ground, the style known as Ku-yueh-hsuan (Guyuexuan, Ancient Moon Pavilion). He made three purchases of this kind: “3 glass Ku yueh hsuan” bought at Christie’s in June 1918 for 15 guineas; “1 Ku-yueh-hsuan in glass" bought from Tonying Co. in July 1919 for £52; “1 Ku-yueh-hsuan brush pot” bought form an unspecified dealer in March 1924 for £150. The last two purchases can almost certainly be identified, although no longer in the collection. A circular glass brush pot decorated in enamels with sages and attendants seems to have been a favourite piece. Hand coloured photographs of this pot were among the photographs found at David Ezekiel’s home, and there is a charming photograph showing Marcus Ezekiel proudly holding this pot in his left hand ("China Without Dragons”, Oriental Ceramic Society, 2016, p.15, fig.5).

I believe this brush pot was bequeathed by Marcus Ezekiel to Sir Percival David, to whom it belonged when it was lent to the 1935 Chinese Exhibition (no.2210). This vessel, now PDF 854, has been much published and is at present on display in the British Museum. The other Guyuexuan purchase was a rectangular brush pot with canted corners, elaborately decorated with coloured enamels in European style, lent by Victor Ezekiel to the Oriental Ceramic Society's 1964 exhibition "The Arts of the Ch’ing Dynasty", no.251. The circular brush pot was also lent to this exhibition, no. 246, lent by the Percival David Foundation, and both are illustrated on pl.85 of the Catalogue.

Ezekiel family tradition (which matches the story I had heard at Bluett & Sons) has it that Percival David (he did not succeed his father as Baronet until 1926) as a young man spent some time at Marcus Ezekiel's home convalescing from some illness. Although the date of this stay is not known it may be significant that Marcus Ezekiel introduced Percival David to Bernard Rackham, Keeper of the Department of Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in 1916 (Stacey Pierson, op. cit., pp.106-7). It is possible that at this time Ezekiel introduced Percival David to the London dealers. Percival David's first purchase from Bluett was made on November 15th 1916, a celadon saucer, and it may just be a coincidence that Marcus Ezekiel bought a celadon shrine from the firm on November 28th 1916. The inference, of course, is that this stay in Hove and the exposure to Chinese ceramics had a major influence on one of the greatest collectors of Chinese art of all time.

Marcus Ezekiel's son Victor (1905 - 1976) grew up in a house full of Chinese ceramics, and it is perhaps not surprising that when, in the mid-1950s, he felt that he was in a position to make a collection of his own he chose to collect in quite another medium, avoiding what another collector of Chinese works of art described as "breakables". It is also not surprising that he chose some aspect of Chinese art as his subject, as he must have heard so many tales of Chinese life from his father.

Among the pieces Victor Ezekiel inherited from his mother (the residue of Marcus Ezekiel's collection) were two jades, two pieces of lapis lazuli, a rock crystal elephant and a turquoise pendant (perhaps lot 85), along with the cabinet of snuff bottles. This may have played a part in directing his attention towards hardstone carvings, and jade in particular. Having been trained in the law he was doubtless a most meticulous man. Evidence of the collection shows that his judgment was good. He joined the Oriental Ceramic Society in 1958, this giving him access to noted collectors and experts with whom he could discuss his purchases.

These included Desmond Gure, a noted jade collector, S. Howard Hansford (he published "Chinese Jade Carving" in 1950 and "Chinese Carved Jades", for the Faber Monograph series, in 1968), and Sir Harry Garner, an expert in many fields of Chinese art. Victor Ezekiel had sufficient confidence in his judgment to buy at auction, but he also made purchases from many London dealers, particularly Louis Joseph. He set himself a limit for each purchase of £100, which was not always adhered to. The animal water pot from the H. R. N. Norton Collection (SP. 111) must have cost him nearly £200 in December 1963 (Lot 55).

Victor Ezekiel was much involved with the Oriental Ceramic Society, serving as a Council Member from 1965 to 1970. He was generous with loans to the Society's exhibitions, "The Arts of the Ch'ing Dynasty" in 1964, "The Animal in Chinese Art" in 1968, and the Society's Fiftieth Anniversary exhibition, "The Ceramic Art of China", in 1971.

Victor Ezekiel’s collection developed to include other materials during the early 1960s. He bought the first of a small group of bronze animals in April 1962 and his first piece of Chinese lacquer in May 1963. He only purchased one ceramic, a very fine Yixing brush rest formerly in the collection of Sir Percival and Lady David, bought at Sotheby’s in June 1964.

The collection was fairly fluid, as Victor Ezekiel weeded out pieces he no longer wished to keep, generally selling at auction, although a few pieces were sold to Louis Joseph, or given away. His first Collection Book has not survived, but the second has, beginning with J.49, which has no description, but was bought from Louis Joseph late in 1958. The last entry, S.153, was purchased at Sotheby’s in May 1972, but is no longer in the collection.

Before his death Victor gave the collection to his son, David. In 1975 Rose Kerr, then a young associate curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, came to David Ezekiel’s home to select some loans for the prestigious Oriental Ceramic Society exhibition "Chinese Jade Throughout the Ages”, held at the museum in May - June 1975. Seventeen pieces were selected, and David Ezekiel was able to take his ailing father, in a wheelchair, to see the exhibition.

David Ezekiel (1930 - 2019) was for more than forty years, with his wife Carolyn, the custodian of the Ezekiel collections. David would always say emphatically that he was not himself a collector but took a keen interest in the objects he had inherited. He joined the Oriental Ceramic Society in 1975 and served on the Council between 2007 and 2010. He was, like his father, generous with loans to the Society’s exhibitions, particularly “The World in monochromes” in 2009 (his grandfather’s blanc de chine magnolia cup gracing the back cover of the catalogue) and “China Without Dragons” in 2016.