“W hen I think of paradise, I evoke Bonnard’s world,” the art critic Jacques Guenne wrote in 1933. If these words had been written 40 years previously, when the French painter was exploring the boundaries of the decorative with Symbolist group Les Nabis, they would have been seen as high praise. But instead, they arrived in the midst of an artistic revolution, which had seen André Breton bending the iconographical rulebook and Pablo Picasso tearing the human form to pieces. “Don’t talk to me about Bonnard,” the latter said. “He’s not really a modern painter.”

And so the story has continued for the so-called “painter of happiness”, with his luminous interiors and picturesque landscapes. While loved by many – “Bonnard is the best of us,” his good friend Henri Matisse proclaimed – he has to this day remained a figure never fully agreed upon or widely understood by the general public. Back in 1998, Tate Gallery joined forces with the Museum of Modern Art in New York to create a blockbuster survey to redress this balance, and yet, more than 20 years on, his art remains something of an enigma. Tate hope to finally change this by unveiling a show that seeks to prove, once and for all, that Bonnard has far more to offer than a pretty picture.

“The objective of this exhibition is to solidify Bonnard’s position as a 20th-century artist, by highlighting his experimental use of both colour and memory,” says Helen O Malley, the assistant curator of Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory. The show will feature around 100 works – paintings, drawings, book illustrations and photographs – made by the artist from 1912, when his style underwent a “radical shift”, until his death in 1947. These include two paintings made in response to life during the First World War – A Ruined Village Near Ham, 1917, and The Fourteenth of July, 1918 – self-portraits and late works such as The Studio with Mimosas, 1939–46.

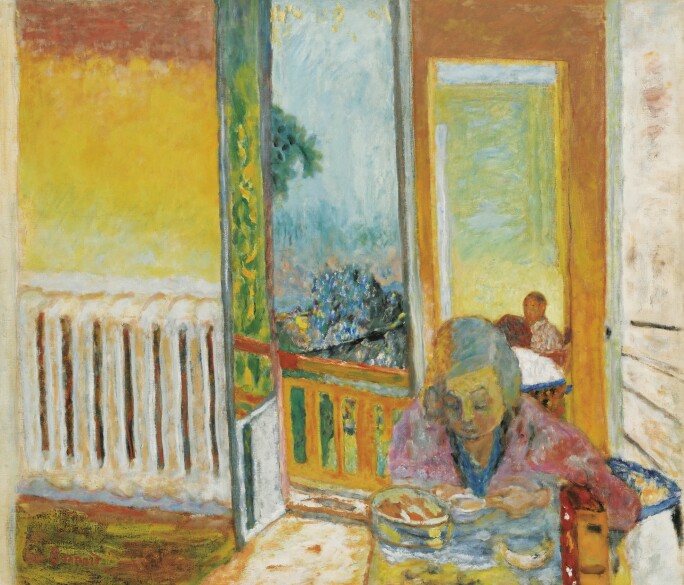

Bonnard worked from memory, using drawings and sketches he had made quickly as reference points. By doing so the artist could “experiment with both composition and perspective”, O Malley explains, and transcend preconceptions of what paint could convey. This is exemplified in domestic scenes such as Dining Room in the Country, 1913, in which Bonnard compresses the space to create a sense of walking into the room of his newly acquired house, Ma Roulette. The interior in this work is as abuzz with blues and purples as the garden it opens out to, and the red of his partner Marthe de Méligny’s dress matches that of the wall below – a revolutionary blurring of inside and out that makes colour the primary means of navigating the composition.

Like many pioneering artists of his time, from Van Gogh to Munch and Matisse, Bonnard found in colour a vehicle for conveying emotion, and from the early 20th century began to “adapt his colour compositions in response to the psychological subject of his work”, O Malley says. Bonnard himself wrote that “one does not only paint out of happiness” and these subjects, contrary to popular opinion, were not always cheerful. He spent nearly 50 years with de Meligny and she appears in more than 300 of his paintings, but their union was saddled with his infidelities (one mistress, Renée Monchaty, committed suicide shortly after he and de Meligny married in 1925). In works such as Nude in the Bath, 1936–38, which shows de Meligny lying in a half-filled tub, her translucent figure eclipsed by the blocks of purple, blue and yellow that surround her, Bonnard “captures the joy and strain at the heart of their complex relationship”, O Malley adds.

But perhaps the quality that really defines Bonnard is the one, ironically, that most irked his greatest critic. “He doesn’t know how to choose,” Picasso continued in his monologue, referring to the Frenchman’s habit of continually adding new colours to his works (he even once convinced fellow artist Édouard Vuillard to distract a gallery attendant while he touched up a work he had “completed” years before). This, Picasso claimed, resulted in a “potpourri of indecision” symptomatic of a painter unable to go “beyond his own sensibility” and “transcend nature” as he believed his own Cubist canvases did.

What the Spaniard failed to appreciate, however, is that Bonnard had little interest in the particular idea of progress Cubism represented: he found, O Malley says, “the strict spatial formula it employed limiting”. Instead, Bonnard preferred a world in constant flux, formed by combining “abstract gestures and three-dimensional construction”, as O Malley describes it, and coloured by the changing emotions he felt towards moments now passed. It is this world that visitors to Tate will discover; and while it may well be a paradise, it is a paradise filled with all the complexity of a truly modern artist.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory, Tate Modern, London, 23 January–6 May

Main Image: Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Summer, 1917. Fondation Marguerite et Aimé Maeght, Saint-Paul- France.