"T hey then harmonised these elements with Iranian culture and brought it to India, creating a synergy with Hindu traditions.” The Aga Khan Museum, established in 2002 by His Highness the Aga Khan, is dedicated to the promotion and conservation of objects deriving from Muslim civilisations. It seeks to “build bridges between cultures”, and this show will explore the lavish world of the Mughal court through a dozen of its paintings and around 90 jeweled treasures lent by Kuwait’s al-Sabah Collection.

The al-Sabah is “one of the most important and prestigious collections of ancient Islamic art”, says Phillip. It was begun in 1975 by Sheikh Nasser Sabah al Ahmed al Sabah and his wife, with 20,000 pieces now housed in the Kuwait National Museum. The objects on loan include weapons, ornaments, vessels and precious stones, many of which embody the melting pot of traditions found in Mughal India.

Phillip and her co-curator, Salam Kaoukji from the al-Sabah Collection, wanted to focus on men’s jewelery and so Emperors and Jewels will explore importance that Mughal princes placed on art and beauty, and illustrate how Mughal jewellery was commissioned, collected and used daily.

The show is divided into sections showing adornments worn by emperors such as Akbar, Jahangir and Jahan; depictions of jewelery in landscape and hunting scenes; and ornamentation on the battlefield. It will emphasise how the value of jewelery from this era lies not just in its aesthetic glory, but in its role as a symbol of status.

This symbolism can often be found within the objects themselves. “The Hindu cosmological navaratna (nine auspicious gems) set in one dagger cord ornament is meant to influence the wearer with positive forces associated with the planets,” says Phillip. “In the centre, the ruby symbolises the sun. Its royal associations add another layer, suggesting that the king is the force around which all other beings revolve.”

More broadly, however, these objects convey meaning simply by existing in a single collection. “International affairs can be expressed through jewelery – [such as developments within the] economy and flourishing trade possibilities,” says Phillip. The Mughals had the power to bring together precious stones from afar – Chinese jade, Colombian emeralds, Persian Gulf pearls – and this helped to establish the dynasty’s rulers on the world stage. “This was part of their statement as emperors, how they positioned themselves globally,” adds Phillip.

Highlights from the Exhibition

Geneaological Charts

The Mughals combined genealogical charts with self-portraiture, highlighting their own importance. The top part of this example shows Jahangir’s court and family in jewel-like cameos; the lower section relates to Babur, who founded the Mughal Indian empire. “It’s all about [remembering] where you came from, and what you have achieved,” says Phillip.

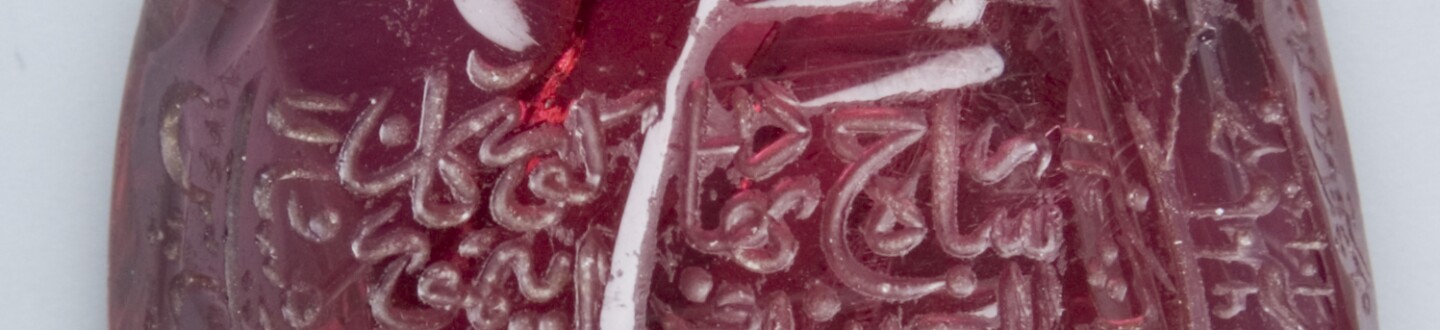

The chart will be displayed alongside the Royal Spinel (see above), which is engraved with the names of six rulers, starting with the Timurid Ulugh Beg. During the 17th century, Shāh Abbās sent the stone as a gift to Jahangir, as a means of emphasising the Persian-Mughal imperial relationship. Their names were added as an ancestral record, immortalising their legacy.

Ceremonial Jade

Tenth-century Arabic sources mention the use of jade by Turkish clans for weaponry and warriors’ belts, believing it to have magical properties as a “stone of victory” that could heal and protect. In Asia, most ceremonial objects were made from or decorated in jade. The Timurid dynasty was equally fascinated by the semi-precious stone – and Mughal emperors elevated it further by adding rubies and emeralds. This cup would have been for ceremonial use. As to what was drunk from it, “I assure you, it was not milk,” says Phillip.

Daggers and Jeweled Weaponry

This dagger’s hilt, with a pommel known in the West as a pistol grip, is in fact an abstract depiction of a parrot’s head. Parrots often appear in Mughal paintings, weapons and jewelery – the exotic bird was particularly loved by Emperor Akbar. This rare black jade piece demonstrates the blending of cultures that occurred throughout Mughal rule: its central Asian background, Chinese influence in material and Indian craftsmanship. It was probably owned by a royal courtier.

Royal Standards

Insignia were used on top of standards in war and for courtly processions. Emperor Akbar rarely left his palace without at least five. Fish standards, especially when combined with a crescent moon, indicated the highest rank at the Mughal court. The fish is a prominent symbol in Persian literature, Hindu mythology (associated with both god Brahma and Manu, a progenitor of humankind), and the Qu’ran. The Arabic letter nun was said to symbolise the fish upon which the globe was placed. This insignia will be displayed alongside another from the David Collection collection in Copenhagen, which shows two fish and probably came from Lucknow. These two works could have been created up to 100 years apart.