Sotheby’s Picasso Prints & Ceramics (19 November–3 December) features a selection of works by the famed artist that were creatively inspired by the female form. Discover more about these works and their history below.

Over the course of two decades, Pablo Picasso created over 3,500 unique and editioned ceramic works fired in clay. Vases, pitchers, jugs, plates and zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sculptural forms abound with animal and classical imagery, mythological creatures, playful and whimsical faces and explorations of the human figure, most notably women. Picasso’s ceramic works were rarely studied or appreciated during his lifetime. However, in recent years his ceramics have enjoyed broader recognition for their inventiveness and originality, showcased in museum exhibitions, sold at auction and collected with fervent enthusiasm. Picasso’s ceramics combine elements of his different practices, fusing painting, printmaking and sculpture. But for Picasso there was something singular about the opportunities that working with clay provided for his creative process. Appreciating the plastic and technical possibilities of three-dimensional forms, he approached ceramics as more than surfaces to be painted.

Recalling his father’s work in ceramics, Claude Picasso has said:

"Working with the primal elements fire and earth must have appealed to him because of the almost magical results. Simple means, terrific effect. How ravishing to see colours sing after infernal fires have given them life. The owls managed a wink now. The bulls seemed ready to bellow. The pigeons, still warm from the electric kiln, sat proudly brooding over their warm eggs. I touched them. They were alive, really. The faces smiled. You could hear the band at the bullfight.”

Looking at his work, it is hard to ignore the more playful and whimsical nature of his ceramics alluded to by Claude. It has been noted that these works were made during a happier and more optimistic time in the artist’s life, after the dark years of the war.

In 1946 while vacationing at Golfe-Juan in the South of France, Picasso met Georges and Suzanne Ramié, the owners of the Madoura pottery studio in the nearby town of Vallauris. The Ramiés welcomed Picasso into their workshop where the artist created three ceramic objects, a head of a faun and two bulls. While Picasso had experimented with clay almost 40 years earlier, this encounter at Madoura so captivated his interest that the artist returned a year later, sketches in hand and his head brimming with ideas. He began working at Madoura daily, completing over 1,000 unique pieces between 1947 and 1948. This was the start of a friendship and creative partnership with the Ramiés that would last until Picasso’s death.

Acknowledging the inherently serial nature of pottery production, Picasso and the Ramiés decided to make multiples of his ceramics that would be sold at Madoura. By this time Picasso was a world-renowned artist, and being well aware of his fame, he wanted to make his work more accessible. “I would like them to be found in every market, so that, in a village in Brittany or elsewhere, one might see a woman going to the fountain to fetch water with one of my jars.” And so, between 1947 and 1971, Picasso designed 633 different ceramic works that were to be made in editions of 25 to 500.

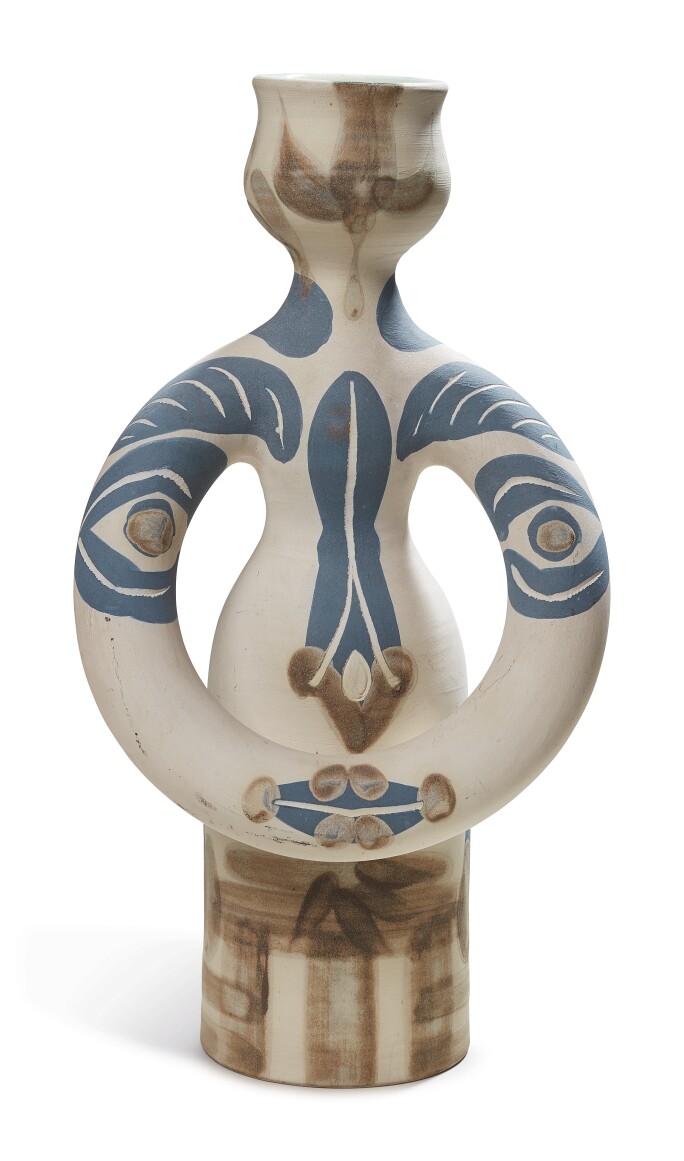

Picasso used deliberate references to ceramic traditions from all over the world, seen most strikingly in his depictions of women. What makes Picasso’s ceramics so remarkable is that he did not merely decorate appropriated forms, he breathed life into them.. By making use of an ancient prototype, Picasso’s Vase deux anses hautes exemplifies the dialogue between ancient and modern that characterises his ceramic oeuvre. It is not coincidental that the curves of his vases such as Vase deux anses hautes mirror those of a woman’s bodies. Picasso stated, “People have said for ages that a woman’s hips are shaped like a vase. It’s no longer poetic; it be comes a cliché. I take a vase and with it I make a woman… I move from metaphor back to reality.”

The idea of transformation was particularly important in Picasso’s ceramic work. This too has classical roots, recalling Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphoses and the transformation of humans into animals. These influences can be seen most strikingly in Chouette femme from 1951. Picasso utilized this zoomorphic shape several times to represent owls with a variety of decorative effects. Owls feature broadly in Picasso’s work, and he found that this complex shape, constructed out of four parts: the body, the head, the tail and the foot, lent itself particularly well to his endeavors. Picasso was also well aware of the symbolic associations of owls throughout the history of art. The owl was the ancient Greek symbol for Athena, the goddess of wisdom, who disguised herself as a bird to help defeat the Persians at the battle Marathon. Owls were symbols of intelligence and courage, and were used on Athenian coins and to decorate pottery.

With Chouette femme, Picasso decorated the avian form with that of a woman. Volume is used as an integral element as the owl’s feathered chest becomes her face and rather than feet, the base becomes her long neck. Instead of wings, on the side of the rounded vessel we see the side of her face. And instead of a tail, Picasso has depicted a woman’s hair elegantly swept back. Here, Picasso is concerned with proportions and a purity of form, creating an organic, living figure.

Several of the forms Picasso decorated were designed by Suzanne Ramié. Suzanne contributed to the revival of the ceramic tradition in Vallauris, using old forms and redesigning them in a late Art Deco Style. While working at Madoura, Picasso was able to use her creations whenever he wanted them, “raiding the drying-boards and carrying off any of the waiting pieces - pots, pitchers or vases intended for everyday use.” One such example is Lampe femme. Here, Picasso has taken the lamp base designed by Suzanne and transformed it into a female figure. Picasso created at least four different editions using Suzanne’s design, experimenting with different stylized decorations and effects. Lampe femme is thus a prime example of the way in which Picasso looked to the past for inspiration while creating something unmistakably modern.