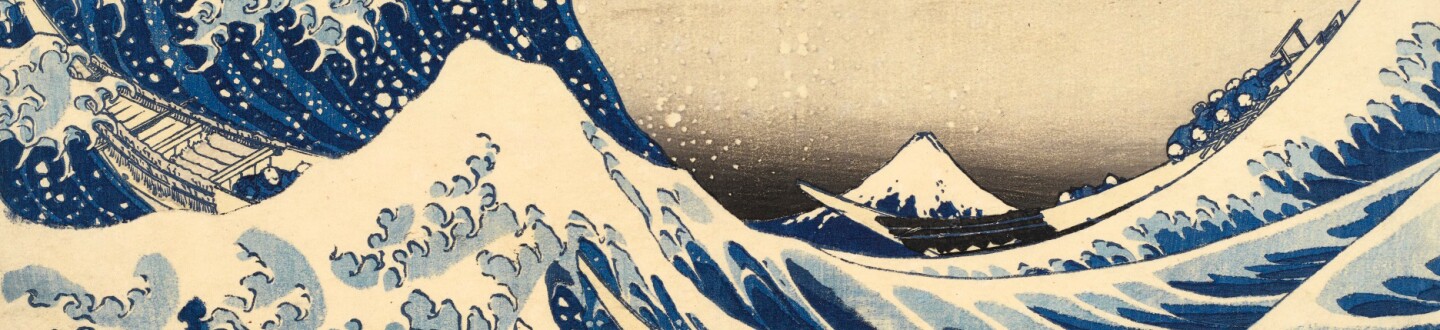

It would be difficult to discuss Japan’s relationship with the sea without thinking about Katsushika Hokusai and the awesome beauty of his masterpiece “Under Great Wave off Kanagawa.” The work conveys the great force of nature as a huge wave is about to crash down upon boats beneath, while the cresting foam on top of the wave wraps around Mount Fuji. “Waves at Matsushima” by Tawaraya Sotatsu is another example in traditional Japanese art that masterfully expresses the dynamic movement of water. Two scenes on pair of folding screens are painted in the Rinpa style and show the dual nature of the sea. Six panels show roiling waves breaking against jagged rock, in stark contrast to the other six panels which depict water gently lapping the beach.

There are many other notable ukiyo-e works similarly devoted to seascapes, including "The Ghosts of the Taira Attack Yoshitsune in Daimotsu Bay" by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. In this Edo period woodblock print, military commander Minamoto no Yoshitsune encounters the ghosts of a vanquished enemy. After a brutal naval battle, the spectres of defeated Taira forces lurk amid the churning waves, silhouetted against a dark sky. The men can be seen lowering the sails as giant waves rise supernaturally, threatening to swallow the ship. This story inspired many similar works, including “Minamoto no Yoshitsune Encounters the Ghost of Taira no Tomomori” by Utagawa Yoshikazu, which show the Taira ghosts waiting in ambush beneath the churning waves. Both prints are perfect illustrations of the deep-seated fear of the sea, as nature poses an even greater threat than the spirits of Minamoto’s archenemy.

As we approach the sea, the sea turns into waves and then in turn becomes water. This is the concept behind a recent installation by art collective Mé (Eye) at the Mori Art Museum. While this work is no longer on exhibit, it is a fascinating meditation on the way two-dimensional depictions of the ocean create distance between the subject and viewer. The work is called “Contact” or “Keitai” in Japanese. “Keitai” is a portmanteau of the words for scenery “keshiki” and substances “buttai” as it brings substance to the seascape in a realistic sculptural installation of waves. This creates an unsettling contact, as the dark sea inside the museum threatens to overwhelm the viewer.

In contrast to the violence of the previous works, the deep quiet of Sugimoto Hiroshi’s “Seascapes” might offer some welcome relief. The series of photographs captures the sea along the horizon at different times of day or night, accompanied by captions which indicate specific designations of time and place— e.g., "Caribbean Sea, Jamaica, 1980" and "North Atlantic Water, Cliff of Moher, 1989". These boundaries are revealed to be arbitrary, even absurd, in contrast with vast expanse of the ocean. Sugimoto poses the question: “Can somebody today view a scene just as primitive man might have?” The relentless calm of the images gives full expression to this idea and serves a reminder that beneath the still waters the sea paradoxically birthed all manner of life and chaos.

These images are displayed within the Enoura Observatory, designed by Sugimoto and first opened in 2017. The observatory is situated on the side of a cliff overlooking the sea, and the structures are aligned to the positioning of sunrise and sunset during the summer and winter solstices. Sugimoto sought to pay tribute to the meeting of water and sky, as our progenitors did at the beginning of time: “Upon gaining self-awareness, our ancestors first tried to find their place within the vastness of universe. This search for meaning and identity was the principal impulse behind art.”