The artist Kawahara Keiga (1786-1860) was born at a time when Japan had imposed a strict isolationist policy of Sakoku. The term literally means “chained country” in which free exchange with the external world was nearly prohibited, with the exception of tightly controlled trade and limited diplomacy. During this time, Keiga became an accomplished artist living within the Dutch community on Dejima island in western Japan. He best known for his work with the doctor Philipp Franz von Siebold to create pictorial records of indigenous animals and plants as well as ethnological observations in Japan. Keiga’s work brought him in close contact with foreigners, and he became a significant figure in transmitting information from a “closed” country to Europe. Although he was a prolific artist, only about 50 paintings remained in Japan while a lion’s share of his works made their way to Holland and Russia.

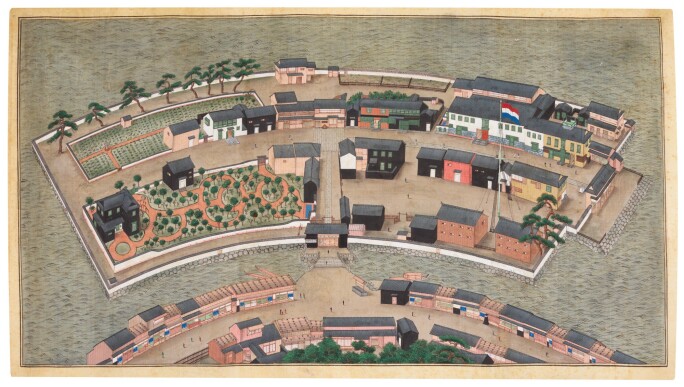

Dejima is an artificial island constructed in Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1634, to accommodate Dutch and Portuguese traders, who were restricted to the small trading post and prohibited from entering the main island without special permission. As foreigners were contained within this tiny community, it became one of the only places where the Japanese and Dutch could interact. Dejima continued to play a central role for trade until 1859, six years after the end of the Sakoku policy.

Born in Nagasaki, Keiga earned the title “painter of Dejima” at the age of 25 and received official permission to enter the outpost. He began to work immediately upon arrival, but it wasn’t until he met Siebold five years after his residency that Keiga drastically changed as an artist. His work with the Dutch doctor aimed to research and collect the flora and fauna of Japan. Keiga painted his subjects with delicate precision and an elegant colour palette. His skills are on full display in the works currently in the collection of The Russian Academy of Sciences Library.

“ Japanese painter Toyosuke’s (Keiga’s) remarkable skills and vivid paint of Japan would not fade in the beauty of nature and actual objects.”

Siebold had praised Keiga in a letter to his assistant, Heinrich Bürger, written at the time the doctor was about the leave Japan. In the same letter, Siebold proposed an ambitious idea to paint all of the species of fish in Japan. Today, more than 300 of Keiga’s vivid fish illustrations are in the National Museum of Natural History, Leiden.

Keiga also painted many landscapes and scenes from the everyday lives of Japanese people. These works were intended for Dutch trading officers and were painted with traditional materials, such as ink and colour on silk, but done with a Western-style perspective or bird’s-eye view. Although the artist was influenced by Western painting, Keiga had a unique style that went far beyond mere imitation. His works have a magical quality specific to that integration of cultures on Dejima.

“Paintings that Dutch can bring back home, are made by the sole painter in Nagasaki,” according to Johan Frederik van Overmeer Fischer in Bijdrage tot de kennis van het Japansche rijk. Overmeer Fischer spent many years in Dejima as a Dutch officer and agent of trade. He regarded Keiga with great esteem and saw in these paintings not only art, but also a rare visual record for Europeans.

Keiga was Siebold’s eyes on Japan, beginning his works through the doctor's explicit direction and sketching subjects with meticulous precision, but he would eventually go on to develop his own style by combining what he considered the best of Western and Japanese techniques. In this, he remained true to his title “the painter of Dejima,”offering Europeans a tantalizing glimpse Japan in the Far East.

In the Fine Japanese Art sale on 5 November in London, 37 lots of paintings attributed to Keiga Kawahara will be featured.