A fter an impeccable result in September with the auction Masterpieces of Chinese Ceramics from the Ise Collection, which achieved an exceptional 99.5 percent sell-through rate, Sotheby’s Chinese Works of Art returns this month with two single-owner collections, Imperial Connoisseurship: Treasures of Chinese Art from a Prestigious Collection and Masterpieces of Asian Art from the Okada Museum of Art on 21 and 22 November.

Encompassing masterpieces from across China, Japan and Korea, the collection of the Okada Museum of Art was assembled over three decades under the guidance of Kochukyo Co., Ltd – the venerated art dealership founded by Hirota Matsushige in 1924, later known as Fukosai. The extraordinary curation represents many of the highest achievements in East Asian art, and reflects the societal and religious values, rooted in a common intellectual foundation, and the political forces that influenced the course of its history.

On the occasion of this collection coming to Sotheby’s, we explore how cultural exchange, diplomacy, trade and war played a role in shaping the rich artistic narrative of these three great civilisations of East Asia.

China, Japan, and Korea: An Interwoven History

The vast region of East Asia is a complex tapestry of history built by centuries of trade routes, and vast political and cultural ties. China, Japan, and Korea in particular share an extraordinarily rich historical coherency rooted in a common written language, intellectual thought and extensive cultural ties.

Accounts of war, conquest and diplomacy paint a picture of brutal pursuits for power and legacy. Take for example China’s glorious and prosperous Tang dynasty (618-907) who allied with the kingdom of Silla to invade the kingdoms of Goguryeo and Baekje on the Korean peninsula. This conquest for power of the Three Kingdoms of Korea was not long-lasting for Tang China, yet various aspects of Tang culture, such as its political structure, and Confucian values, would inevitably be adopted in both the Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago.

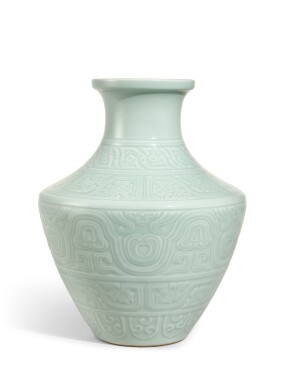

The transformative era of Japan’s Asuka period (538-710) adopted the Chinese model of a single-ruler state governed by a central administration and imperial court. Buddhism, alongside other foreign concepts such as the Chinese written language, the use of coins and standardisation of weights and measures, were introduced from China and the Korean peninsula, profoundly influencing all aspects of Japanese society. By the time of the Goryeo dynasty (Koryŏ, 918–1392), Buddhism had reached its pinnacle influence and was the country's state religion and celadon wares such as the jeongbyeong water vessel was an important ritual object greatly valued in Goryeo's many Buddhist temples.

In the centuries that followed, each country battled threats of war and revolt within and beyond their own borders. China experienced several dynasties: the Song dynasty (960-1279), split into Northern (960-1127) and Southern (1128-1279), was followed by Yuan (1271-1368), returning only to native Han rule under the Ming (1368-1644). Concurrently, on the Korean peninsula, after nearly five centuries of rule, an embattled Goryeo dynasty, already weakened by years of war with the Yuan dynasty, was overthrown to make way for the Joseon dynasty (Chosŏn, 1392–1910). Under the Joseon dynasty, Korea experienced a cultural renaissance, ending only after Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868) and the Tokugawa shōgunate came to an end with the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), along with the fall of the Qing (1644-1911), China’s last imperial dynasty.

Embedded throughout this tapestry of history is a parallel narrative of art and the artistic dialogues between China, Japan and Korea. Neolithic cultures developed multifariously in these three great civilisations, although archaeological findings have pointed to evidence of exchange among these early cultures. However, at a time when Japan and Korea were still in their neolithic era, advancements in China progressed more dramatically, leading to the emergence of a bronze culture that eventually became the foundation for the Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) which brought great developments in the production of stone, bronze, jade and ceramic, and invention of a pictograph-based written language. This in turn trickled into Korea, and later Japan, as both countries transitioned into an agricultural society. Expansionist policies of the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220) became the stimulus for further transmission of Chinese cultural elements into Japan and Korea.

From this moment on, as time progressed, the artistic cultures of China, Japan and Korea each developed distinct characteristics and visual expressions but nevertheless shared many common threads due to the continued cross-fertilization of art through trade, pilgrimage, war and diplomatic exchanges.

The Literati Tradition and the Collective Reverence for Nature

The Tang dynasty was a period of internationalism where diplomatic missions bringing opulent offerings East and West became a chief medium of cultural exchange and the transmission of Confucian philosophy. Landscape painting seeking to capture the beauty of nature was established as a prominent art form while ceramic innovation made impressive leaps not only in glaze techniques, but also incising and carving designs into wares. Tang China was also a popular pilgrimage destination for monks coming from Japan, evident in the Heian period (794-1185) which witnessed a flourishing of Buddhist art.

In the succeeding centuries, waves of artistic influence continued to flow from China eastward to the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago. Although visual expressions varied, China, Korea and Japan all held a strong affinity for the literati tradition, rooted in Neo-Confucianism which integrated ideas from Taoism and Buddhism and was the dominate philosophy of East Asian higher from the Song dynasty onwards.

Take for example, literati painting, which reached its apex in China during this time. Succeeding the Kamakura period (1185-1333), Japan’s Muromachi period (1392–1573) was an era of great artistic innovation. Through pilgrimage and diplomatic relations, Muromachi shōguns amassed great collections of Song and Yuan dynasty paintings and handscrolls. These in turn influenced the evolution of Japan’s own ink painting tradition, most notably among artists of the Kano School – the most influential school of painting in Japanese art history.

Kano Masanobu (1434–1530), credited with establishing the Kano School, had close associations with important Zen temples, and as a result, adopted the style and subject matter of Chinese paintings favoured by monks which had a strong emphasis on ink brushwork. Masanobu’s son Kano Motonobu (ca. 1476–1559) expanded the repertoire, devising a style that merged that of Chinese painting with local Japanese interests in colour and pattern.

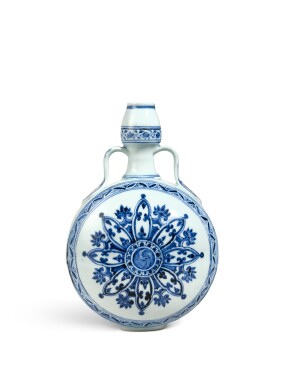

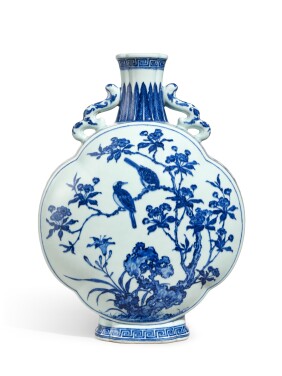

Ceramics and the Dynamics of Trade and Diplomacy

Ceramic wares were frequently exported through trade or gifted during diplomatic missions between China, Korea and Japan, while the migration of potters – often a consequence of the displacement of war – brought with them native skills and tastes. All of this would have a profound influence on the ceramic traditions of both countries.

Jian tea bowls, adapted specifically for tea consumption, was one such export. These thinly potted tea bowls with brown hare’s fur glazes ranging from blue-black to dark chocolate, and rims often bound with silver or bronze, were favoured by many monasteries in the Tianmu mountains, leading to the Japanese name tenmoku for these wares. Chinese paintings, calligraphy and ceramic wares were treated with such reverence in Japan that the Japanese appointed the designation karamono for these imported goods.

On the Korean peninsula, the innovative glazes and kiln techniques of the Song dynasty had enormous impact on the ceramics of the Goryeo dynasty, while later, the exquisite porcelain achievements of the Ming and Qing dynasties played a key role in the ceramic industry of the succeeding Joseon dynasty.

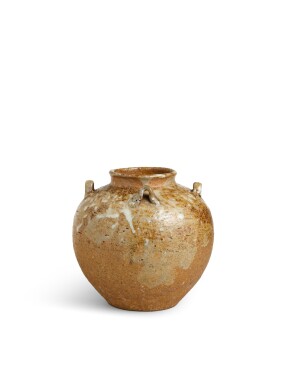

Among the most eminent type of celadon ware to come out of Song China is the incredibly rare Ru. Produced for only a very short period in the Northern Song court, Ru is greatly admired for its subtle glaze which varies from azure sky-blue to milky egg-blue. The most valued aspect of its glaze is the crackle, which can vary from being irregular and thin to “crab’s claw” markings, or the venerated “ice crackle.” Song dynasty celadons exported to Korea, such as Jun wares from Northern Song, and Longquan wares from Southern Song also greatly influenced the development of Goryeo celadon.

Celadon-glazed ceramics constituted the primary type of ware produced during the Goryeo dynasty and marked a key turning point in the history of Korean ceramics. Goryeo potters learned much of the techniques from Song potters, especially through Yue wares from Southern Song. Records show Xu Jing (1091-1153), a Song envoy who visited Gaeseong, the Goryeo capital in 1123, wrote of the resemblance between Goryeo ceramics to the celadons of China’s Ru and Yue kilns. In early Goryeo examples, this influence and conscious emulation of form (for example, the maebyong, derived from the Chinese meiping) and decorative motif can be seen.

By the mid-12th century, native tastes became the main driver of a thriving celadon industry, and Goryeo celadons, admired for its shimmering blue-green hues with a touch of grey owing to the local raw materials, came to be respected in their own right and even exported to China.

[CENTRE] A celadon stoneware inlaid maebyong, Goryeo dynasty, 12th century | Lot sold: 1,524,000 HKD

[RIGHT] An incised and iron-brown painted buncheong vase, Joseon dynasty, late 15th - early 16th century | Lot sold: 190,500 HKD

Where Goreyeo celadon wares demonstrate the emphasis of elegant sensibility in Korean ceramics, buncheong ware, produced during the first 200 years of the Joseon dynasty, arguably embody the experimental spirit of Joseon potters. Striking and distinctive, buncheong wares have a relatively coarse grey body and decoration typically utilised a white slip under the glaze adapted from the inlay technique used by Goryeo potters, with motifs that bear resemblance to sgraffiato decoration of Chinese Cizhou wares, which were exported in vast quantities to Korea. The production of buncheong wares were gradually replaced by porcelain at the end of the 16th century, marred by the Japanese invasions of Korea between 1592 and 1598.

Among the earliest porcelain wares to come out of Korea were blue and white ‘dragon’ jars, possibly inspired by the Chinese blue and white ‘dragon’ jars gifted by the Xuande Emperor (r. 1425-1435) to Joseon’s King Sejong (r. 1418-1450). Such jars became important objects used in royal Joseon ceremonies, however the cobalt required had to be imported through China and as the geopolitics of the region – notably the 1627 and 1636 invasion of Joseon, and subsequent tumultuous dynastic transition of the Ming into the Qing dynasty – made it nearly impossible. As such, the 17th century saw Joseon potters increasingly develop monochrome wares inspired by native materials, including the now renowned moon jars.

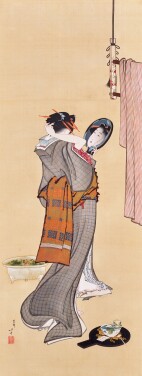

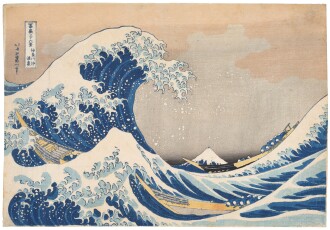

Ukiyo-e in Japan’s Golden Age of Printmaking

Concurrent to China’s period of unsurpassed porcelain achievements of the Ming and Qing dynasties, Japanese arts prospered under the great patronage of the Tokugawa shōgunate. Despite the country’s self-imposed isolationist policies cutting off contact with the outside world, restricted trade with Dutch and Chinese merchants were permitted, which in turn spurred the development of Japanese porcelain and saw Ming literati art seep into scholarly circles in the capital, Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

[RIGHT] A fine octagonal dish, Nabeshima ware, Hizen, Edo period, late 17th – early 18th century | Estimate: 2,000,000 - 3,000,000 HKD

One mode of expression developed out of this period was the ukiyo-e (“floating world”) woodblock prints portraying life in the hedonistic culture of Japan’s pleasure districts, where people were permitted to comingle without the segregation of society that was imposed by the Tokugawa regime. Woodblock prints were produced in large quantities and sold to the mass. Notable artists include Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753-1806) who rose to prominence for his bijin õkubi-e, portraits of beauties with exaggerated features, and for his intimate behind-the-scenes portrayals of the licensed brothels, Kabuki theatres, and teahouses. During the early 19th century, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) further revolutionised the ukiyo-e genre, turning the attention to landscapes. In the decade following the death of Hiroshige, the Meiji Restoration brought about the downfall of the Tokugawa shōgunate, the country heralded the coming of a new modern age, and with that, the tradition of ukiyo-e also came to an end.