The realm of collectable rugs and carpets is one of infinite variety and is all but impossible to summarise in a single article. However, our forthcoming Rugs and Carpets: Including Distinguished Collections sale in London on 23 April, includes a number of examples which offer an excellent way to begin exploring the subject.

Much like any other category of collectable, what defines an item of interest to a collector is a combination of factors. Is it rare, unusual and beautiful? Is it in as good a condition as possible? These elements, when presented alongside a compelling historical context, will pique the interest of even the most reticent collectors. Here we examine a few pieces from the sale, and what makes them particularly collectable.

The court of the Shah

A great many collectable works trace their roots to the influence of the courts of Shah Abbas II (1632-1666). Abbas II, who became ruler at the age of nine, moved his court to the capital of Isfahan in Central Persia. Once established he drew the finest craftsmen from all across the Safavid Empire to work in his court ateliers, subsequently many of these craftsmen returned to their homes with a whole new range of influences.

The above fragment is one of 21 works within the sale from noted collector Christopher Alexander and represents an insight into the type of production stimulated by the Shah’s support for the arts. For an idea of what the design of this carpet might have looked like in its entirety see the ‘Niğde Carpet’ formerly in the McMullan collection and now in the Metropolitan Museum. However, typical of Khorossan production of the period, it has remarkable, saturated colour.

The Khorossan dyers were masters of their craft and were able to produce an extraordinary range of intense and vibrant colours, which the weavers then combined to stunning effect. Whilst a fragment, it exemplifies this tradition and has sufficient extant pile and design to evoke the power of the original carpet. Fragments of early carpets can be as equally collectable as a complete piece. The smaller scale makes them easier to display, the fragment allows focus on the relationship between a specific group of forms or motifs, and the best examples retain the power to evoke a complete tradition of weaving from a particular time and place.

A road paved in silk

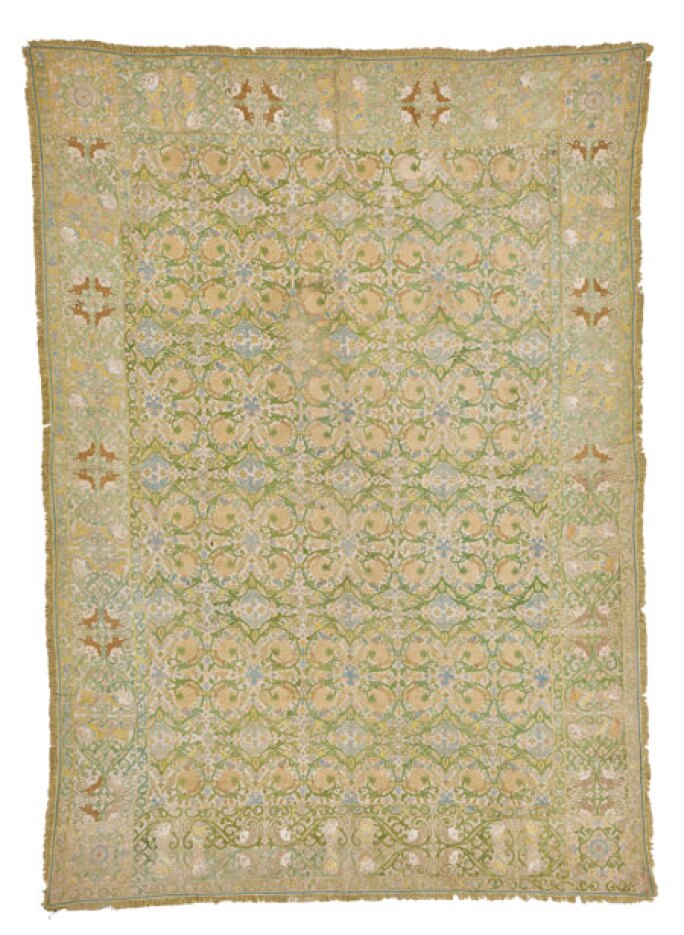

A key factor in the collectability of any rug, carpet or textile is an element of the unknown, we often don’t know quite where it has come from, but we can surmise. The Safavid, Ottoman, Mughal and European kingdoms had a vast and sprawling network of trade routes. They spanned more than 7,000 miles from the farthest eastern point of China to the western tip of Portugal. Merchants would travel these, often dangerous, roads and sea routes with their precious cargo, back and forth from Empire to Kingdom. As a result there is a broad array of influences present in many rugs and carpets.

The Indo Portuguese panel is a perfect example of this. It was most likely made in Portuguese-controlled India, possibly by embroiderers trained by the Portuguese and was intended for the home market. Yet it clearly demonstrates native, and indeed Persian, influence in the use of birds and geckos and also an unquestionably European touch with the figures in the border.

Age isn’t everything

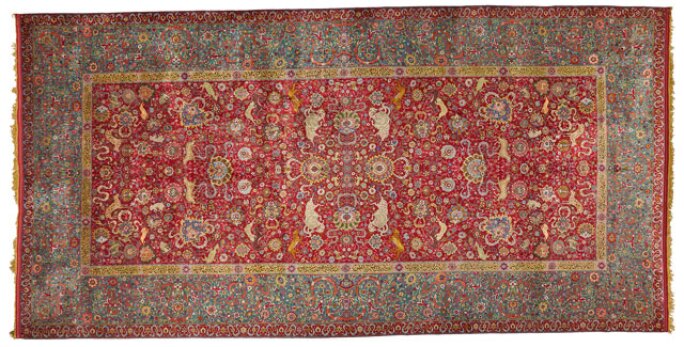

It certainly doesn’t hurt but in the case of the above carpet, which is a Turkish reproduction of a pair of exceptional 16th century carpets known as the ‘Emperor’ carpets, one now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York and the other in the MAK, Vienna, this isn’t so. Sometimes even without having a great deal of context you can look at something and appreciate it, and rightly so. Also, with approximately 9 by 9 knots per square centimetre, this exceptionally fine and beautiful carpet has in excess of 16 million individually hand-tied knots. In this case, quality — of materials and of weaving — is a key element in its value as a collectable.

Surprisingly perhaps, fineness of weave is sometimes a disadvantage. For example early tribal and village rugs were often relatively coarsely woven. Their value lies in the quality of the materials used (lustrous wool is preferable, with clear, lucid vegetable based dyes); in their condition and in the intangibles of drawing and arrangement of motifs. When traditional designs are woven more finely (often in a response to a Western concept of fineness or knot density being directly related to better ‘quality’) they lose the lyrical drawing and sense of space so important to collectors. However, in this case, the fineness of the weave allows an accurate rendition of the earlier model, and its technical expertise, quality of materials used and scale (far larger than any normal production of the Istanbul workshops) make the piece a tour-de-force of early 20th century weaving.

RIGHT: A WEST ANATOLIAN RUG FRAGMENT , POSSIBLY GÖRDES REGION, 18TH CENTURY OR EARLIER. ESTIMATE: £8,000–12,000.

Where did it come from, who was it made for?

A question that could be asked across any collectable category — rugs and carpets included: who was it made for? The provenance, the identity of any previous, or original, owner is an important question as it can often throw extra weight into the authenticity or collectability of any given work.

With carpets, scholarly study really only began in the late 19th century and records are sparse, so it is often the case that we, at present, are unsure of who the original owner was for earlier works. However it is sometimes the case that a gifted amateur collector or even respected collector will offer their collection. We are lucky that in the present sale we have two such groups.

In the first group is the second instalment from the collection of celebrated Berkeley Professor Christopher Alexander, whose work on pattern language had such a dramatic affect that his theories would help to form the basis of wiki technology – ultimately Wikipedia. The results from Sotheby's 2017 Rugs & Carpets sale demonstrate the gravitas rare and beautiful works can have when aligned to a much respected collector.

The other group perviously belonged to Lt. Colonel David Rees Thomas O.B.E, who gathered the few works included within this sale during the 1930s whilst stationed in the Punjab, or modern day Pakistan (lots 1–4). These lots illustrate how usability, fashion and taste can change the way collectors view pieces. Thomas purchased a group of very attractive carpets, primarily for use in furnishing. He passed on a large Mughal carpet and a Mughal saf, either of which today would set the pulse racing of any collector of early weavings, but which obviously didn’t appeal to the Lt.Colonel.

The beginning of the thread

These observations can only scratch the surface of what defines the collectability of handmade textiles, rugs and carpets, but we hope also show how they can offer an insight into our past and the nature of our collective cultures whilst being beautiful and rare works of art.

CLICK HERE for the full sale catalogue.