T his spring’s Arts of the Islamic World & India auction unveils many exceptional artworks, manuscripts and paintings, the legacy of civilizations that coexisted largely under Islamic rule for over 1200 years.

Highlights include a breathtaking nineteenth-century Indian panorama of spectacular proportions, commemorating Tipu Sultan’s triumph over the British East India Company in 1780 at the Battle of Pollilur; a fine selection of medieval metalwork including a highly rare group illustrating 800 years of Islamic silver; a Khurasan penbox and inkwell in remarkable condition, each richly ornamented with silver inlay, testifying to the importance of calligraphy and the Art of the Pen in the Islamic World, and an exceptional Abbasid carved rock crystal cosmetic dish.

From the Ottoman World comes a highly sought-after and elegant Iznik tile of which only eight are known worldwide, with two exotic birds perched on a fountain, and an oil painting depicting the arrival of the Venetian Bailo Francesco Gritti in Istanbul, painted by Pietro Longhi in 1731.

Further notable works include a broad collection of Indian paintings from the Subcontinent’s varied schools including Mughal, Deccani, Pahari and Company; an exquisite watered-steel sword dedicated to the Persian ruler Nader Shah, and a rare 11th-century Qur’an section written in a refined Eastern Kufic script.

Download Full Catalogue

Exhibition Information

| Friday 25 March | 9AM to 4.30PM |

| Saturday 26 March | 12PM to 5PM |

| Sunday 27 March | 12PM to 5PM |

| Monday 28 March | 9AM to 4.30PM |

| Tuesday 29 March | 9AM to 4.30PM |

Auction Highlights

Despite the importance of gold and silver wares in the pre-Islamic period, very few precious metal objects from the Islamic World, produced before 1500, have survived to this day. Indeed, it has been suggested that fewer than a hundred courtly items made of silver exist today, due to a few specific reasons. Most widespread was the custom of melting down silver for recycling into coinage, leading to a scarcity of silver objects when compared to brass and bronze wares from the ninth to fourteenth centuries. It has also been suggested that Muslims were not buried with gifts, and we also know that “the disapproval of precious metal tablewares by pious Muslims appears to have affected production intermittently” (‘Metalwork’, in The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Ed. Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair, Oxford Islamic Studies Online). When works of art made of precious metals were outmoded, they were often melted down. The objects that are found today, largely in museum collections, were generally buried in times of unrest. This is why so many of the surviving medieval objects were discovered in ‘hoards’, most notably the so-called ‘Harari Hoard’, once owned by the collector Ralph Harari, now in the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art, Jerusalem. This group displays a number of diverse silver objects with nielloed decoration and inscriptions, which include jugs, incense burners, rosewater sprinklers and two footed trays (illustrated in Hasson 2000, p.41).

In his article on a silver bottle now in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Boris Marshak gives the following explanation of Islamic medieval silver’s evolution:

“The four centuries (from 750 to 1150) of the history of eastern Iranian and Central Asian silver can be divided into four periods: the Abbasid period up to the first half of the ninth century, when pre-Islamic traditions dominated; the Samanid period, when local and western Islamic traditions met in Khurasan and Mawarannahr; the very end of the tenth century and the first half of the eleventh, when several local schools of silversmiths adopted western Islamic vermiculé backgrounds and developed their own variants of niello ornament; and the second half of the eleventh century and beginning of the twelfth, when, under the rule of the Great Seljuqs, local traditions actively interacted in Khurasan and probably in western Iran.” (Boris I. Marshak, ‘An Early Seljuq Silver Bottle from Siberia’, Muqarnas, vol.21, Essays in Honor of J.M. Rogers, Leiden, 2004, pp.264).

Today, the majority of important medieval Islamic silver is in The L.A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art and The Hermitage, although some important individual pieces can be found in other institutional collections, including a sprinkler in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (F1950.5), a Buyid wine cup in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no.64.133.2) and a lidded jug in The David Collection, Copenhagen (inv. no.36/2017).

The extant silverwork with niello decoration, even though ascribed to a period between the tenth and thirteenth century by scholars, has not been organised in a particular chronological order but can clearly be linked together through their Persian connections attested through their inscriptions: from the fifth-century BC bowl naming the Achaemenid King Artaxerxes I, to several models inscribed with the name of Amir Abu'l-Abbas Valkin ibn Harun, who was thought to be a Daylamite prince of the tenth century (Atil 1985, p.85). Harun, whose name is inscribed on various silver objects with niello ornamentation, is mentioned by Rachel Ward in connection with Buyid metalwork (Ward 1993, pp.54-55). The Buyids, who ruled Iraq and Western Iran from 932 to 1062 AD, constructed their identity by emphasising their Sassanian heritage and marking themselves as "Persian" Kings. The particular notion of inscribing one's name on vessels is attributed by Ward to the tradition of the Buyid's Byzantine neighbours (Ward 1993 p.54).

The present selection of seven items of high-quality silver from the sixth/seventh century to the fourteenth provides an exceptional grouping which illustrates the development of silver workmanship, from early derivations of Byzantine and Sassanian models (lots 83, 84 and 86), to the Harari-Hoard style incense burner (lot 87) and inscribed dish (lot 88). Crucial to our understanding of Islamic silver is the importance of the neighbouring areas of Greater Iran and Central Asia, as exemplified by the parcel-gilt Sogdian saddle cup (lot 85), taking its influence from China and the Silk Road, and the finely-worked Caucasian cup (lot 89), which displays a confluence of Islamic and Christian decoration.

Not only is it important to remember the importance of pre-Islamic Persian heritage and craftsmanship when looking at silver from the Islamic period, but it is worth considering the geography of where many pieces have been discovered. Marshak, discussing the provenance of the silver bottle in the Hermitage, mentions that it was “one of the silver vessels brought to the lower Ob’ basin from the ninth through the early twelfth century by Muslim merchants from Central Asia and Volga Bulgaria. There these merchants sold silver vessels and steel swords to the local Ugrians (the Khanty and the Mansi), who were hunters and trappers, and bought from them excellent sable and ermine furs. In the system of Eurasian trade routes the “Fur Road” was comparable with the famous Silk Road.” (Marshak, op.cit., p.255).

Unlike so many courtly silver-inlaid objects which first appeared in the West via Italy, much Islamic silver (excluding that from Spain) seems to have been traded northwards, exported in trade for furs from Russia. For further reading on the geography of silver finds, a useful resource is www.eurasiansilver.com, where Dr Betty Hensellek has catalogued a multitude of third to thirteenth century silver vessels discovered in hoards across Eurasia, the Urals and Siberia.

The present silver ‘hoard’ serves to remind us of the impressive legacy of Islamic silversmiths over a period of eight hundred years. The various forms, decorative dynamism and quality of the workmanship on display allow us a glimpse of what must once have been an extensive corpus of courtly silver objects.

Read Less

The sale features a small group of highly decorative boxes, including workboxes and a games box, made in the Indian sub-continent in the 19th century. These articles of furniture were produced in ateliers in Bombay, Vizagapatam in India, and the Galle District in Sri Lanka, using a broad range of materials – a variety of hardwoods including sandalwood and teak, bone, ebony and ivory, and metals – arranged in mainly geometric and floral patterns over a wooden base. Showcasing the traditional nature of Indian craftsmanship and techniques passed down through generations, the boxes are of superior quality and reflect the rising demand for these collectable items from British patrons in India and in the West in the second half of the 19th century.

Estimate: 150,000 - 200,000 GBP

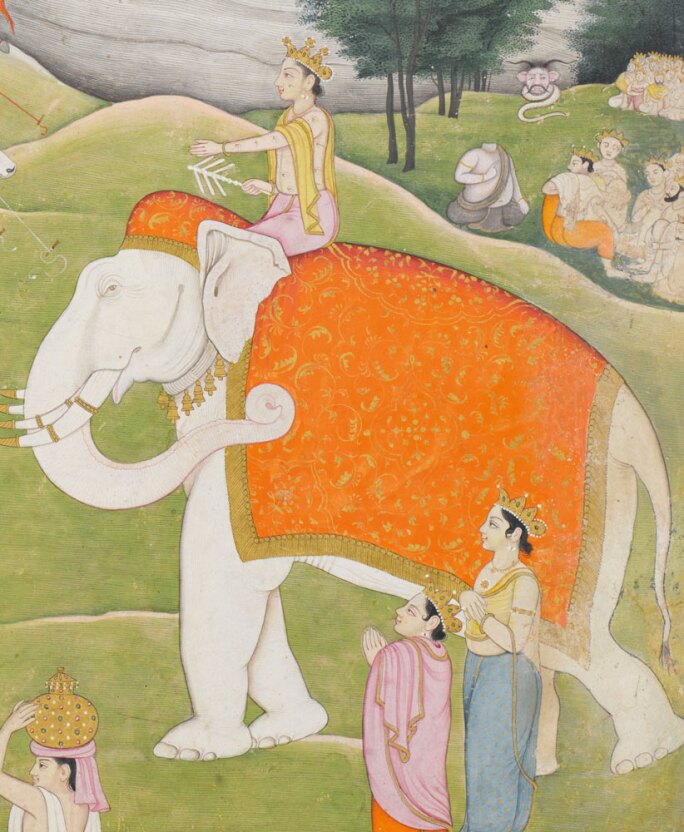

This incredibly detailed painting has been attributed to a master artist from the first generation of the workshop of Manaku and Nainsukh, the most well-known family of artists working in the Punjab Hills, North India, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Click on the red dots to discover more

View Lot

Preparations for the churning of the ocean are depicted in the upper left section of the illustration. The churning of the ocean of milk (samudra manthan) by the gods and the demons is one of the most well-known episodes of the Bhagavata Purana. Mount Meru, the mountain home of Brahma was used as a churning stick, Shiva’s snake Vasuki was used as the rope, and Vishnu took on his second avatar as Kurma (the turtle) to prevent the mountain from sinking. The churning led to several treasures emerging from the ocean, including three categories of goddesses, with Lakshmi being the first. All the gods vied for her attention, but she looked to Vishnu for help and chose him as her husband.

The main subject of our painting is the wedding celebration of the Hindu god Vishnu and the goddess Lakshmi. The couple are seated, with Lakshmi veiled, within an enclosure of tent panels under a canopy.

The four-headed god of Creation, Brahma, is the officiating priest for the wedding ceremony.

The moon god, Chandra, is depicted to the right of Brahma holding a golden water vessel.

Outside the tent enclosure, the other gods have taken possession of some of the other treasures which had emerged from the ocean. Surya, the sun god, is galloping away on the seven-headed horse, Ucchaihshravas.

Shiva, the god of destruction, seated on Nandi the bull, is drinking a cup of poison which had come forth from the great snake Vasuki.

Kamadhenu or Surabhi, the cow of plenty, is being led away by one of the gods.

The Parijata tree with its medicinal properties is being carried off by another deity.

Indra, the king of the gods, is seated on the four-tusked elephant, Airavata. Indra is distinguishable by the thousand eyes marking his body.

Amrita, the nectar of immortality, was another treasure which emerged from the churning. It was immediately grabbed by the demons. While they were fighting amongst themselves, Vishnu assumed the form of his female avatar, Mohini the enchantress. The demons handed over the pot of nectar to Mohini to divide between themselves and the gods. Mohini did not intend to give any of the demons as that would make them immortal. One of the demons, Svarbhanu, realised this and disguised himself as one of the gods. He was soon discovered by Surya and Chandra, and as soon as he had consumed some of the nectar, he was beheaded by Vishnu’s discus. His body fell to the ground, but his head flew up to the sky and became immortal as Rahu, the demon who swallows the sun and the moon in eclipses. This is the scene depicted in the centre right of the painting.