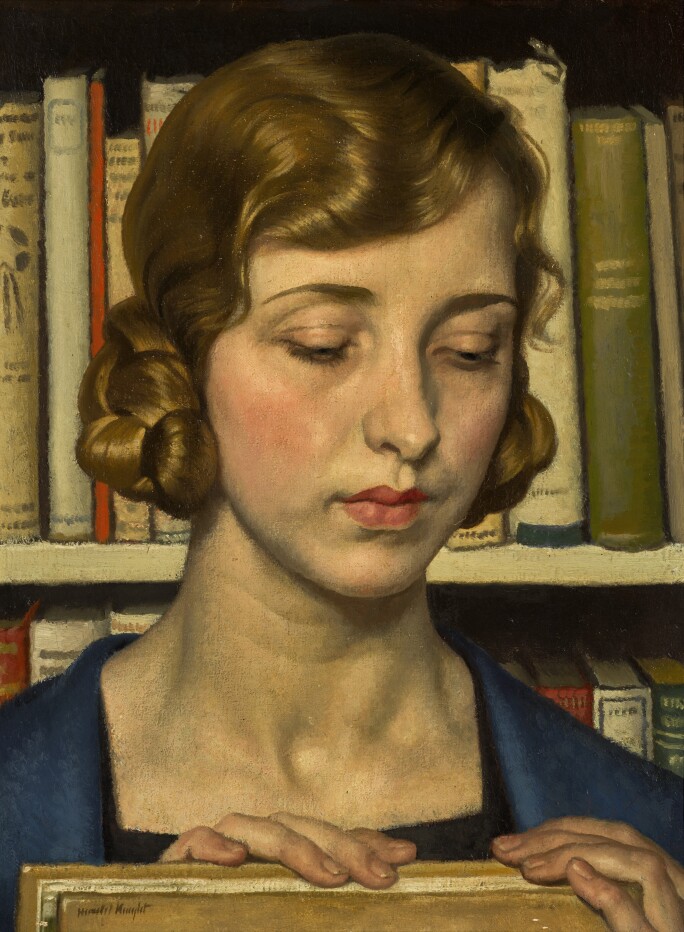

T he 13 December sale of Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art will include a varied selection of works by Dame Laura Knight and a highly sensitive portrait of Laura by her husband Harold in which she is holding one of her canvases and surrounded by books – her hair is fashionably styled and Harold has depicted her as the intelligent, talented woman that he knew and loved.

Laura Knight is best remembered for being the first female artist to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy in 1936 200 years after its establishment. She was made Dame in 1929 and in 1965 she became the first woman to have a large-scale retrospective at the Royal Academy. Although Knight was eventually recognised as the most prodigious female artist of her generation, her path to success was far from straightforward. Knight grew up impoverished and was only able to attend Nottingham School of Art on account of a bursary. As a female, Knight was excluded from life drawing classes and only allowed to study the nude from plaster casts. Through her masterful talent, enduring determination and later institutional recognition she heavily contributed to elevating the status of the female artist.

In 1913, Knight painted the revolutionary painting, Self Portrait with Nude. This subversive self-portrait was the first instance in the history of art of a painting depicting a female artist engaging in the practice of life drawing. This historically significant painting challenged the widespread barring of female students from life drawing classes. The work proved too daring for the Royal Academy, who rejected it. When finally exhibited at the Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers in London, the critic from The Daily Telegraph described it as ‘vulgar’. Knight once commented that ‘a female artist is considered more or less a freak’, a view born out by the views of the aforementioned critic. However, by creating works such as this, Knight was actively opening up a vital dialogue and encouraging a reassessment of the position of women within the art world. There is a drawing in the sale which depicts a naked model casually tidying the study – which may relate to Self Portrait with a Nude.

Knight continually fought her figurative training and she strived to rid her work of the stillness of her plaster-cast studies from art school. She spent a large part of her career striving to capture the complex figurative movement of performers within the theatre, circus and ballet: the gravity-defying bodily contortions of trapeze artists, the dramatic movements of actors, and the elegant yet fast-pasted dynamism of ballerinas. She once commented: ‘I firmly believe the most valuable study I have ever had was in my attempt to draw the Ballet. Never before had I tried to make the pencil speak in a language of its own’.

Knight became deeply involved with her subjects, ‘traveling with the circus, camping with gypsies, setting up easels in circus rings, hanging over the stalls in Covent Garden, sleeping under tent flaps, recording on canvas her impressions of the entertainment world.' The artist relished depicting the contrasting stages of a performance: the frenzied preparation in the dressing room, the quiet anticipation of figures off-stage, and the magnetic excitement of the show.

Knight was also drawn to the entertainment industry as it was much more of an equal playing field for working females. Knight was captivated by the leading female ballet stars, including Anna Pavlova and Tamara Karsavina: ‘For Knight, they were more than performers; they embodied the female artist at the very summit of her profession, a position Knight herself had not yet achieved, but knew would be within her grasp.'

Through her dressing room scenes, Knight captured intimate pictures of performers being prepared for their show. One of Knight’s biographers commented that ‘Laura was undoubtedly happiest when painting informal scenes backstage.' These intimate encounters led to Knight forming close friendships with fellow females in the arts.

In Sotheby’s upcoming Victorian Pictures sale we are presenting an exemplar of Knight’s behind-the-scenes canvases. Motley was painted in Knight’s studio at 1 Queens Road which she transformed into a dressing room for the circus-stars who had finished their season at Olympia in Kensington but stayed in London to pose for the picture. An Irishwoman called Nan Kearns, who was posing as the dresser and would later become a film actress, fed everyone with food from the Cookery School on the Finchley Road.

The studio was crowded and alive with chatter as Knight worked, Whimsical Walker regaling everyone with his tales of stage life. In the chapter titled “Motley” in her brilliant autobiography, Knight described this time; ‘I tried to dissociate myself from the gaiety, but it was overwhelming. The young people were having the time of their lives, and Nan in her Irish way drove her load of fun over us all like a car of Juggernaut.’ The work gives a glimpse into the backstage life normally inaccessible to outsiders: the ballerina looks into the distance in focused anticipation as her dress-maker alters her layered and translucent tutu. The ballerina wears an intricate white rose crown and heavy make-up: finely articulated eyebrows, rogue and vivid red lipstick.

Equally intimate and fascinating are a group of drawings being offered in the December sale which capture back-stage life in the circus – the great stars of the age such as Long Tack Sam, the Chinese juggler, Whimsical Walker and Joe Craston the clowns, trapeze artists and circus ponies. These studies have a wonderful informality and jest for life.

Dame Laura Knight was progressive beyond her time, using her artistic talent to challenge the outdated treatment of female artists. Knight’s virtuosity lay in her ability to translate the excitable atmosphere of the performance in front of her onto canvas for the viewer to enjoy as if they were present. As Timothy Wilcox has aptly concluded, Knight’s ‘conquest of movement was a metaphor for all that she set herself to overcome as a woman artist’ (Timothy Wilcox, Laura Knight: at the Theatre, p.46). Knight single-handedly changed the landscape of the British art world, making it more inclusive as well as driving new reformative attitudes to working females, thereby contributing to the broader emancipation movement.