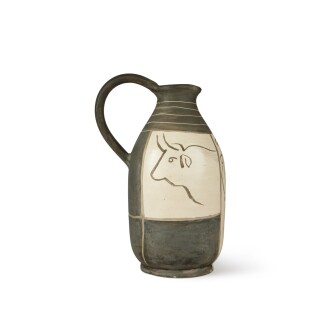

S otheby’s New York is pleased to present Expressions in Clay: Picasso Ceramics from the Ehrlich Collection, open for bidding 11 - 23 November. Over the course of two decades, Pablo Picasso created over 3,500 unique and editioned ceramic works fired in clay. Vases, pitchers, jugs, plates and zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sculptural forms abound with animal and classical imagery, mythological creatures, playful and whimsical faces and explorations of the human figure. The Ehrlichs’ collection provides a survey of Picasso’s ceramic output and highlights from the collection include many of Picasso’s most popular editioned ceramics, such as lot 4, Taureau (A. R. 255), lot 10, Service scènes de corrida (A. R. 416-423), lot 27, Grand vase aux danseurs (A. R. 114) and lot 71, Vase aztèque aux quatre visages (A. R. 402). The collection also comprises several unique works, including lot 28, Plat bachanale (Georges Ramié 1) from 1947 and lot 23, Tête de faune (Georges Ramié 29), and lot 44, Plat aux poisons (en relief) (Georges Ramié 15), both from 1948.

“Working with the primal elements fire and earth must have appealed to him because of the almost magical results. Simple means, terrific effect. How ravishing to see colours sing after infernal fires have given them life. The owls managed a wink now. The bulls seemed ready to bellow. The pigeons, still warm from the electric kiln, sat proudly brooding over their warm eggs. I touched them. They were alive, really. The faces smiled. You could hear the band at the bullfight.”

Highlights

Background

In 1946 while vacationing with his lover Françoise Gilot at Golfe-Juan in the South of France, Picasso met Georges and Suzanne Ramié, the owners of the Madoura pottery studio in the nearby town of Vallauris. The Ramiés welcomed Picasso into their workshop where the artist created three ceramic objects, a head of a faun and two bulls. While Picasso had experimented with clay almost 40 years earlier, this encounter at Madoura so captivated his interest that the artist returned a year later, sketches in hand and his head brimming with ideas. He began working at Madoura daily, completing over 1,000 unique pieces between 1947 and 1948. This was the start of a friendship and creative partnership with the Ramiés that would last until Picasso’s death.

Acknowledging the inherently serial nature of pottery production, Picasso and the Ramiés decided to make multiples of his ceramics that would be sold at Madoura. By this time Picasso was a world-renowned artist, and being well aware of his fame, he wanted to make his work more accessible. “I would like them to be found in every market, so that, in a village in Brittany or elsewhere, one might see a woman going to the fountain to fetch water with one of my jars.” And so, between 1947 and 1971, Picasso designed 633 different ceramic works that were to be made in editions of 25 to 500.

Read LessPicasso and the Corrida

Variations on a Theme

Looking at his work, it is hard to ignore the more playful and whimsical nature of his ceramics. It has been noted that these works were made during a happier and more optimistic time in the artist’s life after the dark years of World War II. Picasso’s playfulness is particularly apparent in a series of round plates he designed in 1963, working from the same basic model, each with a diameter of approximately 255 mm. Between May 16th and June 21st, Picasso decorated over 200 plates, 120 of them on the theme of the face, several of which were turned into editions. The artist experimented with a diverse use of color and glaze; according to Dora Vallier, Picasso ‘gave free rein to series of variations, his line sketching metamorphoses in several directions, developing them at will or abandoning them. The technical procedure in turn added nuance to the colours, differentiating them profusely, making the action of the brush translucent. It is like looking into painting’s own private journal.’

Empreinte Originale

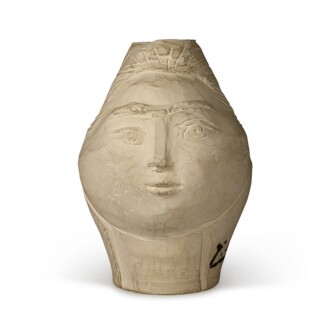

In 1949, taking their inspiration from printmaking, Picasso and the Ramiés developed a method of producing editioned ceramics known as empreinte originale. To complete this process a plaster mould was made of a plate, bowl or vase; once this had hardened, Picasso would carve into or model onto the material to delineate an image. A sheet of prepared clay was then pushed down into the mould to take an impression of the design. Picasso’s compositions thus appeared in reverse – his incised lines became areas of relief, while relief that had been added to the mould resulted in engraved voids and recesses.

From the mid-1950s, Picasso began to leave some of his large empreintes undecorated by glazes or slips – these were called the pâtes blanches. Georges Ramié described this series of works as follows: ‘white or pink biscuit-fired earthenware, engraved in relief, preserving all the freshness they possessed as they were removed from the matrix, without being worked over. In this way they satisfy sculpture’s need for light, which alone can provide it with truth and life.’