T his gorgeous crayon on paper features one of Matisse’s iconic motifs: that of La Danse. Matisse returns to the subject of his famous 1909 Fauvist masterpiece nearly three decades later. Here, we see his sure hand at work in the elegant, curvilinear edges.

The impetus for this piece was Matisse’s his large-scale mural, Danse II, at the Barnes Foundation. That Matisse returned to this subject matter following completion of the mural demonstrates the immense joy brought to him by rendering these figures. Indeed, Matisse wrote to his son about the La Danse II exclaiming "it has a splendour that one can't imagine unless one sees it—because both the whole ceiling and its arched vaults come alive through radiation and the main effect continues right down to the floor... I am profoundly tired but very pleased. When I saw the canvas put in place, it was detached from me and became part of the building" (quoted in Matisse (exhibition catalogue), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1993, n.p.).

Degas’ study of ballet dancers in various stages of preparation and performance is one of the most iconic genres of Impressionist art. These works, primarily done with pastel—as is the case here—are also a window into Parisian society at the end of the nineteenth century and a deeply psychological examination of performers who entertained the social elite. Here, Degas focuses his attention on one dancer, who is in the midst of stretching backstage prior to a performance. She focuses on her craft, averting the eyes of the viewer. Her body is rendered with refined sensitivity, the curves and form of her limbs taking shape through Degas’ adroit manipulation of color and line. Behind her, another dancer saunters behind a neoclassical column, presumably on her way to the stage for her time in the spotlight. Degas, like many upper-class Parisians of the day, had a subscription to the ballet. This enabled him access to the backstage areas, which were the preoccupation of around three-quarters of his compositions from this period.

With his choice of a warm palette, in particular the radiant yellows and greens of the dancer’s tutu, Degas has imbued the entire composition with a sense of vitality. The curator and scholar Anne F. Maheux has discussed the artist’s use of pastel, and the process that he developed to render his compositions with a richness that was unparalleled by artists of his generation. She writes, “Degas’ restless experimentation with combined media eventually evolved into a purer pastel technique, comprised of vigorously hatched, interpenetrating layers of colors that, according to Rouart, were due to his weakening eyesight. The extraordinary textures found in these works…were created by an intense network of bright colors, applied in a spirited variety of squiggles, striations, and prominent crisscross hachures” (Jean Sutherland Boggs & Anne F. Maheux, DegasPastel, New York, 1992, pp. 31-32). This work was once in the collection of Justin Thannhauser, one of the greatest Impressionist and Modern collectors of the twentieth century, whose gift to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum remains of the institution’s greatest treasures.

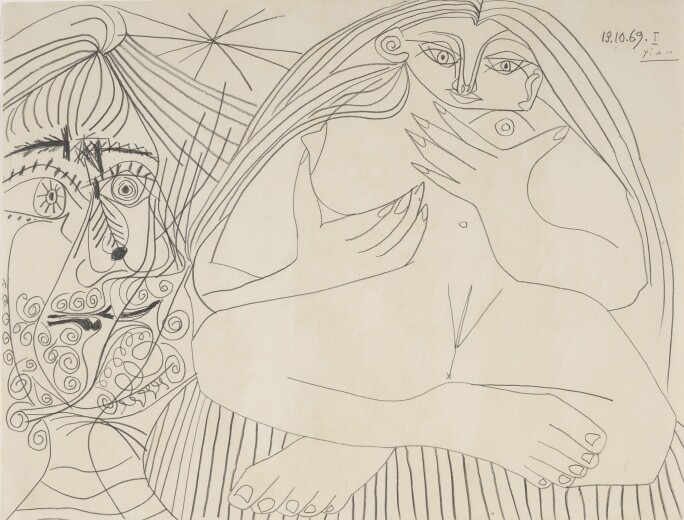

Pablo Picasso’s Nu assis et tête depicts a lascivious voyeur savoring the spectacle of a nude female figure. This very complete drawing belongs to a series of works from the late 1960s that are understood to be thinly veiled references to Picasso and his wife Jacqueline. The majority of these works depict the male figure as an artist. Here, however, the male is stripped down to his most basic, an admirer of the female nude caught in a voyeuristic gaze. Karen Kleinfelder has written, "What is left is the elemental conflict or psychodrama that had been underlying Picasso's treatment of the artist and model theme from its earliest inception: that of man confronting woman, self confronting other, the power of the look, and the play of desire... Picasso, in effect, makes us voyeurs of voyeurism. It is the scopic drive, the gazing impulse, the desire to possess through the look that we witness, and by implication, that we engage in as well. In this sense, the male voyeurs that Picasso depicts also mirror the artist, whose controlling gaze staged this recurring spectacle in the first place" (Karen Kleinfelde, The Artist, His Model, Her Image, His Gaze: Picasso's Pursuit of the Model, Chicago, 1993, pp. 186-87).

Themes of sex and passion would appear in many guises throughout Picasso's final years, such as the virile musketeers and pipe-smoking brigadiers entangled in romantic encounters with women, or the relationship between the painter and his model as depicted in the studio. The artist's choice of a brothel theme here reflects his lifelong admiration for the works of Degas, whose scenes of maisons closes were a potent source of inspiration for Picasso.

This highly unique gouache depicts a large female figure extravagantly pouring a bottle of beer, surrounded by a litany of smaller figures engaged in various activities. The scene is set against a vivid blue sky above the ominous silhouette of industrial chimneys and black mountains and is underpinned by the artist’s words: “Place Pour Le Texte.” The composition is unusual for its commercial intent and was most likely a piece commissioned for a French brewery which was never realized. However, the figures in the background speak to the distinct themes in Kandinsky’s art at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In 1900, Kandinsky was accepted into the atelier of Franz von Stuck; it was here that he rejected the prevailing established Munich School of painting and began to experiment with a more sensuous and symbolic content in his art. Using romantic fairy-tale subjects, such as mounted knights and Russian folk figures, to the right of the composition, he was able to nostalgically reference his homeland. The figures to the left of the composition allude to a more contemporary source of inspiration. In 1906, Kandinsky and his partner Gabriele Münter left Munich to travel to Paris. The couple spent a year in France staying in the small town of Sèvres just beyond the city limits of Paris. Here, Kandinsky became embedded in French artistic society, exhibiting alongside the Fauves and studying the work of van Gogh, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec. The Catholic priest, caped drinker and dashing belle-époque rogue are clear references to this time spent in Paris, where the present work was executed. Kandinsky has also painted an artist into the scene to the right of the woman. He gazes in the direction of this central figure, an easel and palette within reach.

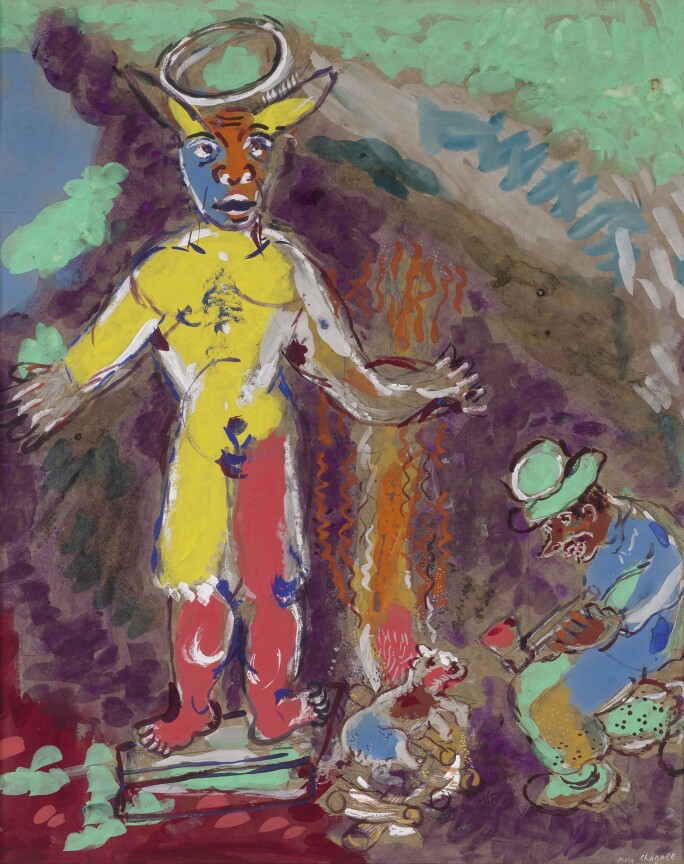

L’Homme et l’idole de bois belongs to a series of gouache illustrations for La Fontaine’s fables, a monumental commission of 120 works which Chagall began working on in March 1926. That Ambroise Vollard had chosen a Russian artist for the project did not go unremarked: critics went so far as to challenge this decision in the National Assembly. Yet, Vollard was unwavering in his selection for this acclaimed and poetic series. He maintained that the task required an artistic sensibility that was “sound and delicate, realistic and fantastical” (Ambroise Vollard, “De La Fontaine à Chagall, in L’Intransigeant, January 1929, n.p.; see fig. 1). His choice was fully vindicated by the acclaimed exhibition of works from the series in 1930 which traveled from Paris to Brussels and Berlin.

L’Homme et l’idole de bois is a beautiful example of the fluid brushwork and bold palette that so impressed his contemporaries, the “fuming reds, opaque blacks, acidic greens, opulent yellows, luminous mauves” noted in L'Art vivant in 1927 by Jacques Guenne, a critic who also remarked on Chagall’s “fabulous invention and touching kindness of spirit” (Jacques Guenne, “Marc Chagall,” in L’Art vivant, December 1927, n.p.). The fable of the wooden idol is a typically ambiguous exploration of human frailty. The pagan worshipper offers up burnt sacrifices to his deaf but “long-eared god” and showers him with gold, “Yet for such worship paid from day to day / He gained no favour, fortune, luck at play / Nay, worse, if but a capful of a storm / Gathered around, in any place or form / He had his portion of the common curse / The god still drew the pittance from his purse” (Jean de La Fontaine, The Fables of La Fontaine, London, 1884, p. 85). The pagan goes on to wreck the idol in frustration at the lack of returns, but in Chagall’s interpretation the man is a hopeful, diminutive figure who gains our sympathies rather than mockery.

As he drafted designs for the fables, his wife Bella would often read them aloud and they would debate the endings. These were some of their happiest years together. The prestigious Galerie Bernheim-Jeune had taken Chagall on in 1926, allaying their financial concerns for the first time and allowing the couple to explore the countryside together. The vivid colors of the French Riviera are particularly evident in his La Fontaine’s gouaches. Chagall completed the corresponding series of etchings by 1930 but to his frustration they would remain unpublished until 1952. The complete set is arguably one of the most important print suites of the twentieth century.

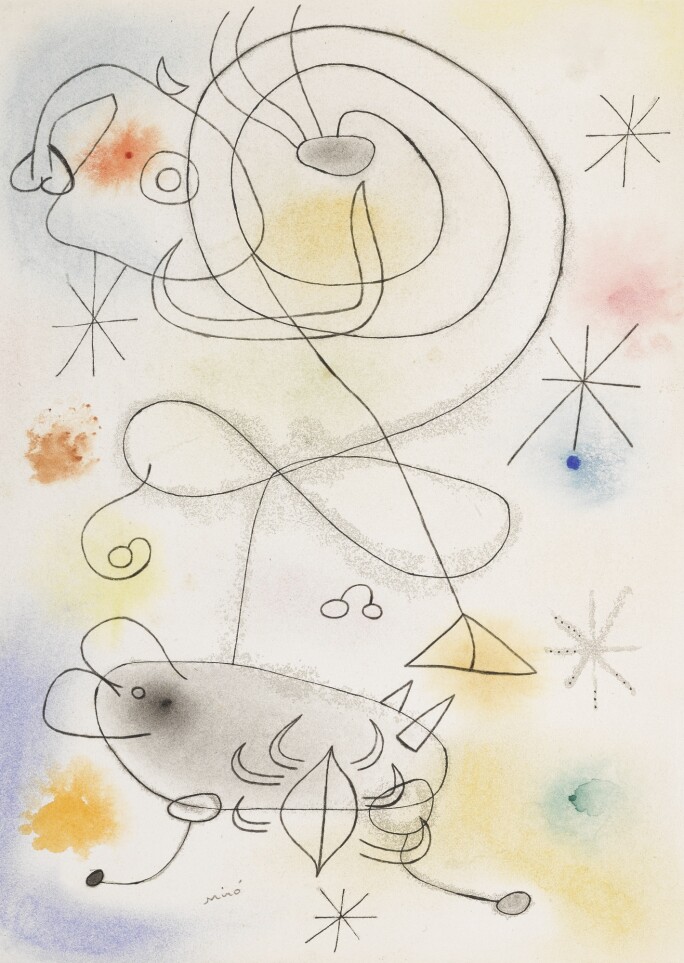

Femmes, oiseau, étoiles was executed in 1942, at a time when Miró was rapidly gaining widespread international acclaim. Populated with highly stylized and abstracted figures, the present work utilizes the vocabulary of signs developed a few years earlier in his celebrated Constellations series. Writing about Miró's production of 1942 and 1943, which consisted almost exclusively of works on paper, Jacques Dupin comments: “They are explorations undertaken with no preconceived idea—effervescent creations in which the artist perfected a vast repertory of forms, signs, and formulas, bringing into play all the materials and instruments compatible with paper. These works permit us to follow the alchemist at work, for errors and oversights are found side by side with the most unexpected triumphs and happy spontaneous discoveries. The object of all these explorations is to determine the relationship between drawing and the materials, the relationship between line and space. The artist is not so much interested in expressing something with appropriate technique, as in making the material express itself in its own way. Successively, on the same sheet, black pencil and India ink, watercolor and pastel, gouache and thinned oil paint, colored crayons...are employed, and their contrasts and similarities exploited to the full, and not infrequently exploited beyond their capacities” (Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró, Life and Work, London, 1962, p. 372).

The present work exemplifies the expressive power of images, even though they bear no faithful resemblance to the natural world. Miró is solely reliant upon the pictorial lexicon of signs and symbols that he developed over the years. A technique of primary importance in this painting is Miró’s expressive and exquisite use of line. Overall, his remarkable visual vocabulary strikes a perfect balance between abstraction and image-signs. His pictures from the mid-1940s are characterized by a sense of energy and movement; there is never a sense of stasis. Moreover, each work is the result of active and ongoing improvisation that renders a precise interpretation impossible. In fact, it was these compositions from the mid-1940s that would inspire the creative production of the Abstract Expressionist artists in New York.