T he New York Sales at Sotheby’s this November mark the inauguration of the auction house’s new headquarters in Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist masterpiece. Open for public viewing beginning November 8, eight auctions will be led by three stunning single-owner collections – The Leonard A. Lauder Collection, The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection and Exquisite Corpus – each with evening and day sales. Rounding out the week will be curated auctions of contemporary and modern art.

Read on for a preview of the evening auction highlights, and explore day sale highlights here.

Leonard A. Lauder, Collector

The Vision of Leonard A. Lauder: A Once-in-a-Generation Collection Coming to Sotheby’s

On November 18, The Leonard A. Lauder Collection will offer a once-in-a-generation survey of 20th-century masterpieces that personifies the lifelong connoisseurship of one of the greatest collectors and benefactors of the arts in America.

Gustav Klimt’s ‘Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer)’

The Hidden Power Behind Gustav Klimt’s Most Daring Portrait

Standing at the apex of Gustav Klimt’s career, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer befits the couple who commissioned it – Serena and August Lederer, the artist’s most important patrons. In this magnificent portrait, Klimt brilliantly captured the social prominence and beauty of the sitter, the Lederers’ daughter Elisabeth, through the painting’s lush ornament details, complex palette, dazzling brushwork and carefully choreographed iconography. Commanding and seductive in scale (measuring 6 by 4 feet, or 183 by 122 centimeters), Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer was realized when the artist was at the height of his powers and reputation as the premier artist of Austrian modernism.

Gustav Klimt’s ‘Blumenwiese (Blooming Meadow)’

Painted likely in the summer of 1908, Gustav Klimt’s Blooming Meadow constitutes a more liberated and daring view of a colorful flowering garden than any of the artist’s earlier landscapes devoted to the subject. As the florescence of viola, green, yellow and white daubs spreads before the viewer, the yellow blooms intensify in an oval-shape just below a thicket of green, and thickly painted white clouds float on a ribbon of brilliant blue. By comparison, the tree foliage might appear simply a deep, saturated green, until the yellow daubs (possibly still-ripening fruit) emerge amid the deftly applied, slightly longer strokes of violets and bluish grays.

The eye could easily lose its bearings in this flat, kaleidoscopic carpet of hues; indeed, some of Klimt’s critics thought his landscapes to be the work of a madman, so radical were their compositions. But even with the heightened degree of abstraction, the pictorial effusion captures the wildflowers native to the lake Attersee region: bellflowers, buttercups, clover, cornflowers, daisies and dandelions, all blossoming simultaneously during the peak season. Such flowering meadows still abound in the region, and with time, Klimt’s contemporaries came to regard his renderings as a set of “new eyes” through which to look at nature.

Gustav Klimt’s ‘Waldabhang bei Unterach am Attersee (Forest Slope in Unterach on the Attersee)’

One of Gustav Klimt’s most complex and stylized landscapes, Waldabhang bei Unterach am Attersee (Forest Slope in Unterach on the Attersee) is unique among this body of work because it depicts not only the hillside but also views from both sides of the Austrian lake. Between 1914-16, the artist spent his last three summers living near his regular companions, the Flöge family, in a remote forester’s lodge in Weissenbach on the Attersee’s southern shores. It was there, opposite the small town of Unterach, that Klimt painted Waldabhang bei Unterach am Attersee during his final summer stay in 1916.

One of only three known views of Unterach from this period, the present work is also believed to be the last surviving landscape ever painted by Klimt. He executed a subsequent, smaller landscape depicting the village of Bad Gastein in 1917 after returning to his Vienna studio; however, like the fate of many works owned by the Lederer family, it is likely that Gastein was confiscated by the Nazis and destroyed in the 1945 fire at Immendorf Castle where their works had been stored.

Agnes Martin’s ‘The Garden’

Can Stillness Be Seen? The Brilliance of Agnes Martin

Executed in 1964, The Garden is a singular painting from the artist Agnes Martin’s early grid series. Unique in its composition of colors and hues, the work presents a delicate array of white, creamy yellow, and pale green rectangles set within a latticework of muted grey. It is among the most intricately conceived examples of the series, which Martin began in 1960, and measures 72 inches or 6 feet square. This format, manageable enough to allow the artist to reach across her canvas and hand-draw her gossamer grid of pencil lines across its breadth and width, is still large enough to project an expansive and sensory optical field: light, space, rhythm, vibrations and movement gently cascade.

Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Le Semeur dans un champ de blé au soleil couchant’

Executed in July 1888 at Arles, in the south of France, this drawing is one in a suite of fifteen that Vincent van Gogh sent to his friend and colleague, Émile Bernard, who was working in Brittany that summer. Through an exchange of letters and drawings, van Gogh and Bernard kept abreast of one another’s ambitions and accomplishments in a period of great innovation and productivity for both.

Like others in the suite sent in mid-July, this drawing replicates a recently completed painting— – in this case one that van Gogh had “wanted to do for such a long time”: a scene of farm labor in a plowed field, set against “a sky almost as bright as the sun itself.” In his pen-and ink rendering of his long-dreamt-of painting, a radiant, low-hung sun backlights a light-footed farmer who moves across the furrows of a field alive with pen strokes of varied size, orientation and density. Traversing it on a diagonal, this solitary figure is intent on the task of casting seeds drawn from the pouch strapped to his chest.

The Now & Contemporary Evening Auction

On November 18, The Now & Contemporary Evening Auction will feature artworks that capture the seismic shifts from the latter half of the 20th century through to the era-defining output of the present day.

Kerry James Marshall’s ‘Untitled’

Kerry James Marshall’s Work With Double Vision in Pleasure, Fantasy & History | Sotheby’s

Radiant and insurgent, Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled from 2008 is a profound and radical reappraisal of the discipline of figurative painting, accentuating and responding to the glaring omission of Black representation in the canon. Previously an iconic centerpiece of the artist’s seminal 2016 exhibition Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, which opened at the Met Breuer, Untitled makes a triumphant return as part of Sotheby’s inaugural Breuer exhibition, a defining moment of both auction and art world history.

The presentation of this exquisite work at auction coincides with the largest exhibition dedicated to Kerry James Marshall ever staged outside of the United States, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, demonstrating exceptional and enduring institutional support for the artist’s practice. A masterpiece of unparalleled formal rigor and graphic grandeur, Untitled is an entrancing embodiment of Kerry James Marshall’s revolutionary painterly practice.

Barkley L. Hendricks’ ‘Arriving Soon’

Barkley L. Hendricks’ Arriving Soon: An Icon of Cool and Power

Among the most recognizable images of Barkley L. Hendricks’ limited and legendary body of work, Arriving Soon announces the artist’s ineffable cool at an operatic scale, reconciling the technical profundity of the Old Masters, the playfulness of Pop and the incandescent theatricality of the Baroque. Executed in 1973, the work possesses a monumentality and narrative complexity so singular and arresting that it reigns virtually unparalleled as a masterwork by the artist.

Hendricks worked thoughtfully and methodically, producing at most around a dozen portraits a year; he largely halted his painting practice from 1984 to 2002, during which time he devoted himself to photography, making works of this caliber rarer still. The tight corpus of canvases he left behind today stands as a testament to the vitality, humanity, individuality and charisma he afforded his subjects, all the while redressing the absence of Black figures in the genre of portraiture.

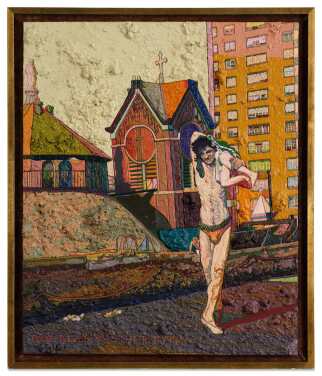

Jess’ ‘Fig. 6 – A Lamb for Pylaochos: Herko, N.Y. ’64: Translation #16’

A Rare Jess Portrait and a Shocking Cady Noland: Stories Behind the Byron Meyer Collection

Crystallizing from an extraordinary, ample mass of oil impasto, Fig. 6 – A Lamb for Pylaochos: Herko, N.Y. ’64: Translation #16 belongs to the rare and institutionally prized series of Translation paintings by San Francisco artist Jess. Executed in 1966, the present work is one of 32 canvases that comprise Jess’ seminal body of Translations, more than half of which are housed in prestigious museum collections, including The Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Philadelphia Art Museum; Art Institute of Chicago; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among many others.

Based on a photograph taken by George Herms, the present work depicts Fred Herko, the avant-garde dancer and fixture of Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, on a Lower East Side rooftop with Herms’ daughter Nalota hoisted over his shoulders. Like the other Translations – and virtually the whole of Jess’ mature output – the work recontextualizes found imagery and historic texts, simultaneously unifying and abstracting their intellectual, mythical and spiritual power into a staggeringly lucid pictorial constellation.

Having been shown in an early exhibition dedicated to the first 26 Translations at The Museum of Modern Art in 1974 entitled Projects: Translations by Jess to Michael Auping’s exuberant mid-career retrospective, Jess: A Grand Collage 1951–1993, organized by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery from 1993-94, Fig. 6–A Lamb for Pylaochos: Herko, N.Y. ’64: Translation #16 hails from the collection of San Francisco-based collector and legendary museum patron Byron R. Meyer.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s ‘Crowns (Peso Neto)’

From Downtown to the Breuer: Basquiat's 'Crowns (Peso Neto)' Returns to New York City

An intricate tapestry of spiritual, secular and symbolic allegory, Crowns (Peso Neto) is a defining masterwork that encapsulates Jean-Michel Basquiat’s unrivaled capacity for creative genius and introspection. Executed on Christmas Day in 1981, just three days after his 21st birthday, Crowns (Peso Neto) marks the culmination of an ascendant year in Basquiat’s brief yet meteoric career – one that would bring hitherto unprecedented public visibility, critical acclaim and commercial success to the artist, as he metamorphosed from vanguard street artist-provocateur to prodigy of New York’s cultural avant-garde.

Rendered at a monumental scale in a medium that evokes the artist’s transition from street to studio, the present work interweaves secular and spiritual imagery to create a profoundly intimate portrait of Basquiat on the cusp of explosive stardom and reflects a poignant meditation on the sacrifices inherent to that success. Boasting an illustrious exhibition history, which includes the artist’s very first solo exhibition in America and, after his untimely passing, his first retrospective, the work has been a hallmark of the most critical showcases of Basquiat’s work. A triumph of artistic mythmaking, Crowns (Peso Neto) is an unrivaled manifesto of Basquiat as painter, celebrity and product; heir, rebel and prophet.

Yves Klein’s ‘Sculpture éponge bleue sans titre (SE 167)’

Yves Klein’s ‘Sculpture Éponge Bleue’: A Vision of Infinite Blue

Sculpture éponge bleue sans titre (SE 167) stands as a masterpiece within Yves Klein’s visionary oeuvre. From a natural stone base rises a constellation of sea sponges, their every ridge, cavity and aperture resplendent with a mystical ultramarine, bearing witness to Yves Klein's most influential contribution to the annals of modern art history: the unending celebration of immaterial sensibility. The present work is among the most momentous examples of the revolutionary artist's brief but paradigm-shifting career; at once organic and otherworldly, it is an unsullied salute to blue as a symbol of absolute freedom beyond corporeality.

Executed in 1960, SE 167, in its enthralling hue, gestures us to follow its path in transcending art as we know it: “We absolutely must realize – and this is no exaggeration – that we are living in the atomic age, where all physical matter can vanish from one day to the next to surrender its place to what we can envision as the most abstract,” Klein said. “I believe that for the painter, there exists a sensuous and colored matter that is intangible. … It is no longer a question of seeing color but rather of ‘perceiving’ it.”

The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection

Inside the Visionary Legacy and Collection of Cindy & Jay Pritzker

Coming to auction on November 20, The Collection of Cindy and Jay Pritzker, carefully assembled over nearly 50 years, stands as one of the most discerning ensembles of Modern and Impressionist art, revealing an instinct for works of art historical significance and aesthetic power.

Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Piles de romans parisiens et roses dans une verre (Romans parisiens)’

A Unique Van Gogh Self Portrait, Without Van Gogh

Piles de romans parisiens et roses dans une verre (Romans parisiens) is one of the most important still lifes that Vincent van Gogh ever painted and the largest in scale to come to auction since the late 1980s. It was painted towards the end of van Gogh’s time in Paris in the final months of 1887. One of only four still lifes featuring books that the artist executed during the course of his two years in the French capital, this work is further distinguished by its exceptional exhibition history and unique combination of visual motifs as well as the tour de force application of medium.

Paul Gauguin’s ‘La Maison du Pen du, gardeuse de vache’

La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache, painted in summer of 1889, is an evocative example of Paul Gauguin’s Pont-Aven style. Painted in Le Pouldu, a village situated several miles east of the busier town of Pont-Aven, the present work captures the bucolic landscape and seascape of this remote part of Brittany.

The late 1880s and early 1890s were the most crucial and fruitful of Gauguin’s career. Through several stays in Brittany, time in Paris, a trip to Martinique and his famed collaboration with Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Gauguin’s artistic practice and signature style and imagery developed into one of the most recognizable in modern art. It is from this period that La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache springs, a canvas which synthesizes the impact of the tropical colors of Martinique, Van Gogh’s florid brushwork and the impact of Japanese prints. Gauguin described his approach as a “synthesis of form and color,” where art becomes an abstraction derived from nature through dreaming and imagination.

Henri Matisse’s ‘Léda et le cygne’

Matisse: A Hidden Masterpiece in the Pritzker Collection

Henri Matisse’s triptych Léda et le cygne (1944–46) occupies a distinctive position within his oeuvre as one of his most complex and ambitious commissions. Conceived in 1943 for the Paris residence of the Argentine diplomat Marcelo Fernández Anchorena and his wife Hortensia, the work absorbed the artist for nearly three years, during which he created dozens of variations on the subject. The final composition reimagines the classical myth of Leda and the Swan with an economy of line within a decorative framework that heightens the drama of the central scene. Restraining the corporeal monumentality of Leda to the central panel, Matisse gilded the two flanking volets in gold leaf, applied a layer of vermillion paint and incised delicate foliate motifs that rise vertically across their surfaces.

Upon completion, the Anchorenas declared the painting “even more beautiful than we had imagined,” praising its grandeur as surpassing “everything we know in modern painting.” The triptych reinterprets a theme explored by Michelangelo, Titian and Paul Cézanne, yet Matisse infused it with a distinctly modern sensibility defined by clarity, rhythm and sensual immediacy. In Léda et le cygne the ornamental and the narrative are inseparable, affirming Matisse’s belief that “the characteristic of modern art is to participate in our life.” Soon after, Aimé and Marguerite Maeght acquired the triptych directly from the Anchorenas for their personal collection of pioneering modernism, where it remained with the family for over three decades before entering The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection.

Max Beckmann’s ‘Der Wels (The Catfish)’

Two Masters of German Expressionism: Kirchner & Beckmann | The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection

Painted in November 1929, Der Wels (The Catfish) stands among Max Beckmann’s most ambitious and important works of the late 1920s, created during a triumphant period when the artist lived primarily in Paris. Measuring over four feet square, the canvas captures Beckmann at the height of his creative power, as he sought to establish his reputation alongside the great masters of the French capital, from Picasso and Braque to Matisse.

The painting takes its title from the enormous freshwater catfish native to European rivers, which Beckmann once described as a metaphor for “the terrible, thrilling monster of life’s vitality.” In the work, a muscular fisherman wrestles with his catch, its tail still thrashing and its eyes wide open, while female figures recoil in a mixture of horror and fascination. The scene is charged with allegorical meaning, the fish embodying both fertility and danger, its symbolic power underscoring the tension between vitality, sexuality, and mortality that preoccupied Beckmann throughout his career.

Félix Vallotton’s ‘Femme couchée dormant (Le Sommeil)’

Félix Vallotton’s tightly composed painting of a slumbering woman is among his most vivid and accomplished interior scenes. Painted in 1899, Femme couchée dormant (Le Sommeil) depitcts Vallotton’s new bride Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques (née Bernheim). The couple married in May of that year, triggering a complete change in the artist’s way of life and a significant shift in his practice.

Exquisite Corpus

Julio Torres & St. Vincent Enter the Surreal with Kahlo, Dali, Tanning, and More

Also on November 20, Exquisite Corpus stands among the most distinguished private collections of Surrealist art, representing the culmination of a lifetime’s engagement with one of the 20th century’s most revolutionary artistic movements.

Frida Kahlo’s ‘El sueño (La cama)’

Why Frida Kahlo's El sueño (La cama) Could Break the Auction Record

Frida Kahlo’s El sueño (La cama) from 1940 is among the most psychologically resonant and formally compelling works in the artist’s storied oeuvre, a surreal, deeply introspective self-portrait that bridges personal symbolism, Mexican cultural iconography and Surrealism. Painted during a particularly fraught moment in Kahlo’s life, El sueño (La cama), or The Dream (The Bed) in English, occupies a critical position within her practice, encapsulating her lifelong preoccupation with mortality, physicality and the emotional complexities of selfhood. Reappearing to the international market for the first time in 45 years, El sueño (La cama) stands to break not only Kahlo's auction record, but the record for any work of art by a woman artist.

Kahlo's most important subject was herself; she painted more than 56 self-portraits in total (the most of any artist in the Western canon, aside from Rembrandt), the majority of which are now held by major museums around the world, and El sueño (La cama) is one of the largest and most complex of these remaining in private hands. She depicts herself asleep; delicate green leafy tendrils stretch around her body, binding the body to natural cycles of decay and renewal. Above her rests a skeleton wrapped in strings of dynamite crowned with a vibrant bouquet. The skeleton, known in Mexican tradition as a calaca, is crowned with celebratory flowers, unmistakably invoking the iconography of Día de los Muertos -- where death is not feared but commemorated, ritualized, remembered, and made familiar. Though she draws from the iconography of Surrealism and its fascination with the unconscious mind, here Kahlo is deeply grounded in lived experience and cultural specificity; as she said herself, "I don't paint dreams. I paint my own reality."

Dorothea Tanning’s ‘Interior with Sudden Joy’

Ernst & Tanning, Sage & Tanguy: Surreal Love Stories Behind Their Works

A pivotal figure in American Surrealism, Dorothea Tanning forged a singular path that bridged the movement’s European origins and a distinctly American sensibility. After moving with Max Ernst to Sedona, Arizona in the late 1940s, she found the desert environment so overwhelming in its intensity that she turned inward, creating richly imagined interiors that became arenas for her most probing psychological explorations. Painted in 1951, Interior with Sudden Joy is a landmark example of this vision: a spectral, meticulously staged scene where youthful figures, cryptic inscriptions, and surreal objects come together in a mood of quiet unease.

Kay Sage’s ‘The Point of Intersection’

The Point of Intersection at once invokes solitude and limitless expanse, mystery and possibility. Executed in 1951-52, The Point of Intersection is among Sage’s most haunting compositions – its scaffolding-like forms and taut, silken drapery suspended in an atmosphere of uncanny stillness. The work dates to the apex of Sage’s output and has been featured in several exhibitions central to her lifetime international recognition, including the 1952 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting at the Whitney Museum of American Art (now the Whitney Biennial).

Salvador Dalí’s ‘La Ville’

In November 1934, Salvador Dalí and his wife Gala arrived in New York for the first time, traveling there on the occasion of the artist’s highly successful second exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery. Shortly after his arrival in New York, Dalí was commissioned by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst to create illustrations for one of his publications, The American Weekly. Dalí published seven illustrated articles between December 1934 and July 1935, and would continue to provide illustrations through 1938, a record of his impressions of daily life in the United States.

La Ville is the original drawing for an illustration published in the 31 March 1935 edition of the paper, accompanying an article by Dalí titled “The American City Night-and-Day.” The characters who feature within these vignettes appear to be conceived as the manifestation of stereotypes – the denizens of the city as Dalí both perceives and imagines them to be, enacting a critique of underlying social structures which is at once satirical and exactingly sharp.

Max Ernst’s ‘J’ai bu du tabourin, j’ai mangé du cimbal’

A vision of charged symbolism as well as surreal beauty, J’ai bu du tabourin, j’ai mangé du cimbal of 1940, reflects the drama of Max Ernst’s circumstances during this period as well as that of the wider political situation in Europe.

The composition is dominated by a shamanic figure, seemingly bearing two heads – one equine, the other ineffable – atop a humanoid body, a surreal permutation of the mythical centaur. The enigmatic figure floats above the clouds, surveying an apocalyptic landscape below. In a prophetic gesture, he conjures a wispy, bird-like form – perhaps an ethereal manifestation of Loplop, the bird avatar through which Ernst often inserted his presence into his work. The creature hovers as a diaphanous, spectral presence, its ghostly appearance heightening the sense of otherworldly observation, bridging the cosmic and the terrestrial, and emphasizing the painting’s dreamlike logic.

The Modern Evening Auction

Capping off a night of events on November 20, The Modern Evening Auction features highlights from The Matthew and Carolyn Bucksbaum Collection, the The Geri Brawerman Collection and The Phillips Collection, showcasing artworks that capture the spirit of artists working around the globe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

René Magritte’s ‘Le Jockey perdu’

Among the pantheon of images reimagined and recontextualized by René Magritte throughout his career, the horse-and-rider motif exists as one of the most recognizable and defining of his oeuvre. Executed in 1942, at the prime of the artist’s technical bravura, Le Jockey perdu represents a radical foray into the Surrealist milieu and stands as the most exceptional depiction of the subject in oil.

Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Restaurant Rougeot II’

Dubuffet and Magritte’s Rare Masterworks: Inside the Bucksbaum Collection

Standing before Jean Dubuffet’s Restaurant Rougeot II, one can almost hear the clatter of dishware, boisterous laughter, symphony of conversation and spectacle of Parisian nightlife. Dubuffet’s jubilant scene immediately transports the viewer to mid-century Paris, capturing the joie-de-vivre and vibrant atmosphere that characterized a burgeoning era of prosperity and hope in the post-war period. Returning to the bustling urban milieu in Paris after years spent in the Venice countryside, Dubuffet was captivated by the city’s potent sense of optimism and liberation in the wake of World War II.

Executed in 1961, a revolutionary year in Dubuffet’s oeuvre, Restaurant Rougeot II is an early example from the artist’s most celebrated and coveted series: the Paris Circus. Dubuffet’s paintings from this limited body of work are poignant vignettes of a rejuvenated Paris: featuring storefronts and street signs, automobiles and local establishments, and city dwellers strewn about wide boulevards. In these works, Dubuffet harnesses a masterful fusion of figuration and abstraction, generating a sensation of unbridled energy through kaleidoscopic coloration and vigorous brushwork.

A rare and seminal painting within the Paris Circus series, Restaurant Rougeot II is one of an exceptional suite of just three paintings depicting Restaurant Rougeot, which was once a vibrant enterprise located on the Boulevard Montparnasse.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘Large Dark Red Leaves on White’

After relocating to New York in 1918 at the invitation of gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe quickly integrated herself into the city’s American modernist art scene. By August of that year, O’Keeffe visited the Stieglitz family summer house on Lake George for the first time, establishing a longstanding tradition of seasonal sojourns between Manhattan and Lake George that pose a strong impact on her artistic output of the 1920s. “I was never so happy in my life,” O’Keeffe wrote of her time on Lake George (in a letter from O’Keeffe to Elizabeth Stieglitz, dated January 1918). The exposure to nature proved mentally restorative for the young artist, and the richness of the colorful Adirondack landscape inspired her creative development tremendously in the years that followed.

Dated to 1927, Large Dark Red Leaves on White hails from an immensely productive moment in O’Keeffe’s early career when her fascination with the still life tradition, the juxtaposition between realism and abstraction, and a deep attraction to nature dominated her practice. Executed at the Lake George estate of Stieglitz's family – whom O’Keeffe married in 1924 – O’Keeffe documented the lively garden, and surrounding landscape with heightening curiosity throughout the ’20s. Large Dark Red Leaves on White is one of the most highly stylized and intricate leaf renditions she ever produced, showcasing her unique ability to transform the natural landscape into avant-garde subject matter that redefined the parameters of both the still life and landscape traditions.

Wifredo Lam’s ‘Ídolo (Oyá / Divinité de l’air et de la mort)’

–My return to Cuba meant, above all, a great stimulation of my imagination, as well as the exteriorization of my world,” Wifredo Lam once said. “I always responded to the presence of factors which emanated from our history and our geography, tropical flowers, Black culture.”

Ídolo (Oyá/Divinité de l'air et de la mort) belongs to a series of monumental paintings that mark the most important period of Lam's career. Since his departure for Madrid in 1923, Lam had remained in Europe, his painting enriched by encounters with Surrealism – notably in Paris, under the aegis of André Breton and Pablo Picasso – and by the Afro-Antillean culture that he witnessed, from Martinique to Santo Domingo, along his journey to Havana in the wake of World War II. The extraordinary paintings that he made between upon his return there, among them Ídolo (Oyá/Divinité de l'air et de la mort), distill the creative syncretism of his practice, commingling modernism and the rich cultural imaginary of Afro-Antillean religions in myriad recombinant forms.

Among the most iconic works of global modernism, Lam’s compositions from these Cuban years subsume New World cosmologies within numinous, hybrid figures – plant, human, divine – that play out a vivid drama of transculturation. Ídolo (Oyá/Divinité de l'air et de la mort) and its arrival at auction this fall are complemented by a major retrospective exhibition of Lam’s oeuvre at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Wifredo Lam: When I Don't Sleep, I Dream.

Claude Monet’s ‘Vue de Rouen depuis la côte Sainte-Catherine’

Inside The Schlumberger Collection: From Monet to Lalanne

-

Art + ObjectsEverything Is Art: Joseph Beuys | Sotheby's

Art + ObjectsEverything Is Art: Joseph Beuys | Sotheby's -

Pauline Karpidas: The London CollectionStep Inside Pauline Karpidas’ Eclectic London Home Featuring Magritte, Dalí, Picasso, Warhol & More

Pauline Karpidas: The London CollectionStep Inside Pauline Karpidas’ Eclectic London Home Featuring Magritte, Dalí, Picasso, Warhol & More -

The New York SalesA Rare Jess Portrait and a Shocking Cady Noland: Stories Behind the Byron Meyer Collection

The New York SalesA Rare Jess Portrait and a Shocking Cady Noland: Stories Behind the Byron Meyer Collection

Dating to circa 1892, Vue de Rouen depuis la côte Sainte-Catherine was painted during Claude Monet’s visit to the city of Rouen the same year. One of the first works executed during that pivotal trip, it forms a critical part of the artist’s exploratory process which culminated in his celebrated series depicting the majestic Gothic façade of the Rouen cathedral, widely considered as the triumph of the Impressionist movement. Executed on a superb scale, the present work captures the iconic motif of the Rouen Cathedral situated amidst a sweeping vista of the city, its distinctive three-spired silhouette captured from the overlook of the hill of Sainte-Catherine during a brilliantly-hued sunset.