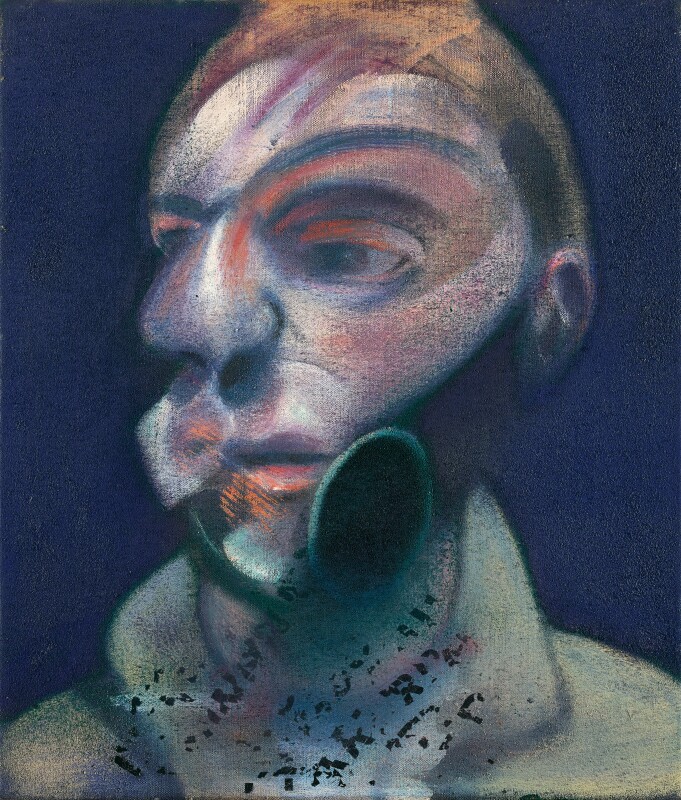

S elf-Portrait, 1975, is undoubtedly one of the best iterations within Francis Bacon’s acclaimed pantheon of self-images; a body of work that is today considered one of the artist’s greatest achievements, sitting him squarely among the ranks of art history’s celebrated masters of the discipline: Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Picasso. Startling in colour, bold in gesture, and unmistakably Baconian in effect, this painting is a masterwork of self-interrogation.

Considered the most introspective and inwardly scrutinising phase of his career, Bacon’s 1970s production is characterised by the searing self-images that emerged following the sudden death in 1971 of Bacon’s former lover, George Dyer. Bacon never truly relinquished the guilt and responsibility he felt in fuelling Dyer’s tragic juggernaut of a life, and the suite of large-scale ‘black triptychs’ painted between 1971 and 1974 offer exorcising lamentation over his death.

"I’ve done a lot of self-portraits, really because people have been dying around me like flies and I’ve had nobody else to paint but myself”

Produced in tandem with these works, Bacon’s self-portraits proliferated and became increasingly complex. Across these mournful paintings, both large-scale and in the intimate 14 by 12 inch dimensions, the artist appears as a modern-day allegory for melancholia, leaning on a washbasin, with facial features violently mutilated, or with his wristwatch prominently emphasising life’s transience. Whether heroically scaled or intimately proportioned, the self-portraits form a link to Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray: where Bacon’s grief was stoically concealed from life, the canvases became the face of his suffering and pain. Although the major work of Bacon’s mourning came to an end with the black triptychs in ‘74, the spirit of George Dyer and practice of self-portraiture endured, fed by an ever-increasing number of bereavements as Bacon grew older.

Not long after George Dyer in 1971, the artist’s Soho companion and Vogue photographer John Deakin passed away, followed by the Colony Room’s famous matriarch, Muriel Belcher in 1979, and in 1980 Bacon’s decisive link to the French intelligentsia, Sonia Orwell, died after a long battle with cancer. These losses famously led Bacon to proclaim: “I’ve done a lot of self-portraits, really because people have been dying around me like flies and I’ve had nobody else to paint but myself” (Francis Bacon in conversation with David Sylvester, 1975 in: David Sylvester, Looking Back at Francis Bacon). However, by the time of the present work’s execution during the decade’s midpoint, the opening of a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and his growing success in Paris ushered in a tonal change that signalled the beginnings of a great late style.

Although a sense of captured movement is apparent in the 1975 Self-Portrait, Bacon’s features remain remarkably intact. This painting does not possess the carved tangle of physiognomic forms or time weariness evident in self-portraits from the immediate years post-Dyer; instead, it emanates an alert youthfulness.

Characteristically taciturn when asked to explain his work, Bacon endlessly insisted his paintings were not expressing anything at all. Contrary to this however is the tremendous body of scholarship through which art historians have unpacked an arena of multifaceted allusion and inference; lines of inquiry sparked by the immense repertoire of source material that Bacon used.

At first driven by a masochistic impulse to inhabit his guilt more intensely, Bacon was drawn back to the site of Dyer’s suicide, to the very hotel in which he had died only 48 hours prior to the opening of Bacon's Grand Palais retrospective. Paris, the very centre of Bacon’s artistic aspirations, was thus forever cast under the tragic and fantastical shadow of Dyer’s demise, and yet it became an incredibly successful location from which to work. With the length of his stay increasing each time, Bacon’s need to paint demanded a proper place in which to work, and in June of 1975 – shortly after the execution of the present painting – he took up a studio apartment in the Marais district at 14 rue de Birague. Bacon’s growing legendary status in Paris, set in stone by his wildly successful show at Galerie Claude Bernard in 1977, truly characterise the period: many of the mid-to-late 1970s works exude a curious mix of the intellectually stimulating and exhilarating ambience of Paris and a melancholic introspection.

The present work represents a moment of clarity and growing resolution for an artist emerging from the pain of mourning that had deeply afflicted his work of the past four years. Bacon’s features are here rendered with an exuberant chromatic palette and appear fully resolved; this painting exhibits the ebullient self-regard and virtuoso confidence of an artist operating at the very height of his creative faculties.