T he first mention of the name Eugène Printz appears in the official catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925, in the description of Pierre Chareau's study-library, exhibited in the French Embassy’s pavilion, which says “James, Pelletier et Printz, exécution de l’ébénisterie”, 12 rue Saint-Bernard, Paris.

Eugène Printz’s father had trained him in the French classical style of cabinetmaking many years before, and he took over his father and uncle's workshop in 1905. He began to produce pieces for Pierre Chareau in 1919 and started exhibiting his own designs at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in 1926, with a rosewood bedroom that referenced his training as a traditional cabinetmaker but already showed signs of his future style. The following year at the Salon d'Automne, he broke with his father’s teaching and embraced the architectural simplicity of his mentor, Pierre Chareau. He used innovative materials, like kekwood combined with lacquered metal doors in a sideboard decorated by Jean Dunand, the first collaboration between the two artists. Léandre Vaillait described the piece as the “masterpiece of the Salon” in the magazine Le Temps.

Jean Dunand had a solid reputation by 1927 and his work could be found in many museums. As the greatest French dinandier and lacquerer, he had brought manual metalworking back into fashion and had been exhibiting pieces with dinandier at various salons since 1905, to great critical acclaim. He tirelessly elevated the art of dinandier to a more noble rank and contributed to the furniture designs of Eugène Printz and Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann. Although he preferred to work with lacquer, dinandier was his first love. He would encrust the non-precious metals with gold and silver, then highlight certain parts using oxidation or blacken others for the piece to remain precious. Jean Dunand would adapt to his client. When working with Eugène Printz, he always produced geometric designs that concealed the furniture and its doors and handles, leaving nothing more than a beautiful geometric illusion.

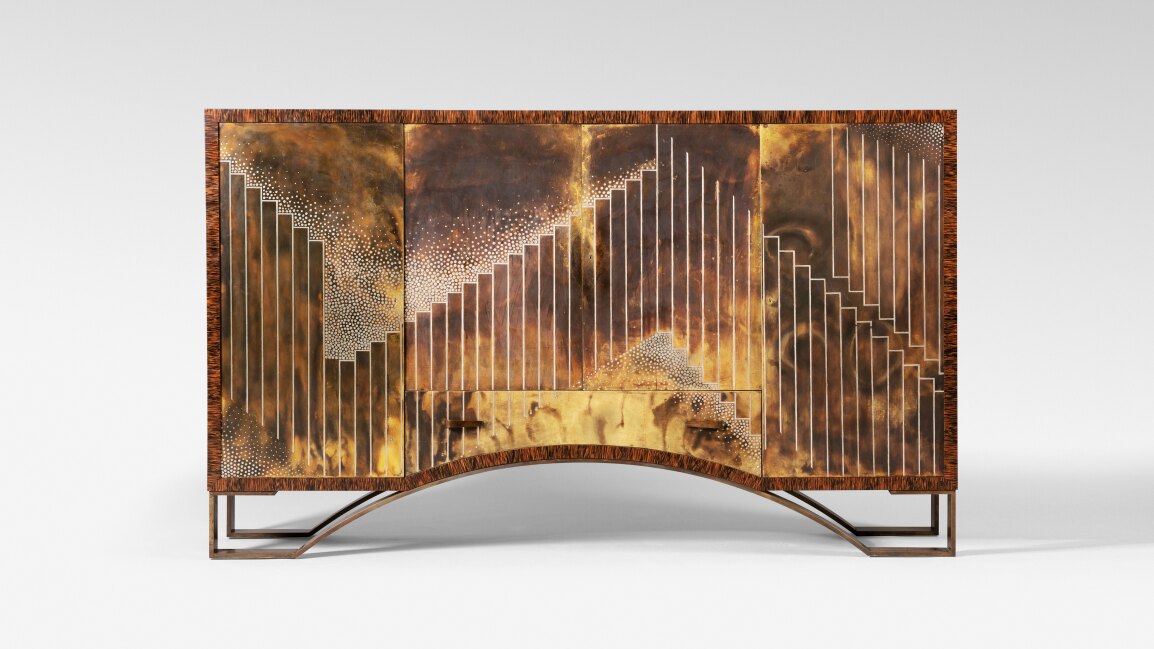

At the 1928 Salon d’Automne, Eugène Printz dazzled critics with a palm wood piece with metal doors decorated by Jean Dunand and a Rio rosewood interior. The extremely simple rectangular block was raised from the floor by metal feet, and the entire beautifully-decorated front was as stunning as any of Jean Dunand's finest screens, making the admirer forget the furniture itself. With this geometric décor, etched in silver on a background of patinated and blackened dinandier metal, Eugène Printz pushed beyond the sideboard’s primary function and brilliantly asserted his identity and talent, to unanimous critical acclaim. In only two years, he had established his own style in the art world, with somewhat austere shapes in the finest and most innovative materials combined with metal and brass, where the functional role of the furniture disappeared behind the most striking of décors, all standing on the lightest and most inventive bases.

On June 21st of the same year, Eugène Printz opened a gallery in his name at 81 rue de Miromesnil in Paris, with the official approval of Paul Léon, the French government’s Fine Arts attaché. It became a majestic showcase for Printz's designs that hitherto had remained in his workshop on Rue Saint-Bernard. At the “Galerie Printz”, his pieces were displayed alongside Jean Dunand's vases and screens, rugs by Evelyne Wyld and fabrics by Hélène Henry, just as they had been on most of his Salon stands since 1926. The gallery's catalogue presents works by all these artists, with an obvious emphasis on those of Eugène Printz. There is a photograph of our piece with the description: “Wooden sideboard with palm wood veneer, Rio rosewood interior, four doors and a bottom drawer, set on two metal arches that end in a Greek key. The front is entirely covered in metal with a silver design by Jean Dunand”. The catalogue also gives the sideboard’s price, by far the most expensive in the whole list, selling for 40,000 francs.

Not only is this clearly an exceptional piece, it is extremely rare for such an iconic work to reappear on the market ninety-one years after it was first exhibited.