O ne of the most significant post-war and contemporary art collections patiently assembled over decades of laser-focused pursuit lands at Sotheby’s New York for the first tranche in November, followed by a second stellar act in May.

Comparisons to The Macklowe Collection are hard to come by, though certainly the Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art-loaded collection from the estate of Robert C Scull that came to auction at Sotheby’s in 1986, and the Victor and Sally Ganz trove of superb examples of Modern and contemporary art that broke records at Christie’s in 1997, are era-defining reference points.

Those remarkable sales began with taxi mogul Robert Scull in a standalone evening sale that included James Rosenquist’s 86ft-long, multi-paneled F-111 painting that fetched a record $2.1 million, surpassing the artist’s previous auction high of $66,000 made in 1983 with Volunteer. Covering that sale for the Washington Post, I quoted the artist’s dealer Leo Castelli in the saleroom moments afterwards, who stated, “I didn’t expect it to get that much. It is a very cumbersome painting.”

The dealer recalled that when it was first shown at his gallery in 1965 during the nascent protest era of the Vietnam war, “it went all around the gallery. Sixty thousand was the asking price, but Scull paid $45,000 (with a discount). It was a very brave thing for Scull to do. He almost deserved to have it for nothing.”

The artist was also on hand that evening and told this reporter about the cover lot entry: “I’m still numb but I do know one thing. I never signed the picture. Maybe I will now for a million.”

That same evening, Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills, from 1962, scaled at 80 1⁄4 by 92 1⁄4 inches sold for $385,000 against an estimate of $175,000–225,000, and Jasper Johns’s Double Flag, also from 1962 and jumbo sized at 98 1⁄4 by 72 1⁄4 inches, made $1.76 million against a pre-sale estimate of $1.5–2 million. Any of those Scull paintings, if they appeared again on the market, would break the deepest of pockets.

When the equally unrivalled collection of Victor and Sally Ganz came to Christie’s 11 years later, the art market had grown up and proved itself with more outstanding results, to the tune of $206.5 million, including Pablo Picasso’s stunning Les femmes d’Alger (version 0) from February 14, 1955, that sold to London dealer Libby Howie for $31.9 million against an estimate of $10–12 million and Jasper Johns’s White Numbers from 1959 that sold to Swiss dealer Doris Ammann for $7.9 million against expectations of $5–6 million. When the Picasso returned to market in May 2015, it sold at Christie’s for a record shattering $179.3 million. Victor and Sally Ganz had acquired all 15 of the sensational series in June 1956, barely a year after they were painted, from the legendary Parisian dealer Daniel Kahnweiler for the princely sum of $212,053.

The breadth of The Macklowe Collection presents a wide-angled view of both European and American masters, ranging from Pablo Picasso’s Surrealist-inspired steel sculpture Figure (Projet pour un monument à Guillaume Apollinaire), conceived in 1928 and enlarged in the current version in 1962, to Tauba Auerbach’s rapturous and crinkled acrylic on canvas painting Untitled (Fold) from 2011; from Alberto Giacometti’s astonishing caged sculpture in bronze, steel and iron, Le Nez, a lifetime cast conceived in 1947 and the current example in 1949 from a Susse Fondeur edition of six, to Jeff Koons’s bronze and equally existential Aqualung from 1985.

Remarkably, or so it seems from this observer, those two works were acquired from wildly different sources, with the Giacometti hailing from the late and legendary Swiss dealer and eponymous museum founder Ernst Beyeler from circa 1994, and the Koons from his first solo show.

It is almost needless to say that the market values of both artists at their time of acquisition were slivers of their currency today, and further attests to the collection’s unparalleled access to the best and brightest, deftly secured way ahead of the crowd.

“If this was a collection that was put together in the last five years, you’d say, ‘Oh, these were people with infinite amounts of money who bought the list,’” says a seasoned New York art dealer. "When the Koons was bought, he wasn’t on any list.”

Thinking about some of the works that came to the collection in the 1980s, two late and luminously minimal paintings by Willem de Kooning, Untitled IV from 1983 and Untitled XIII from 1984 were purchased in London in 1987 from the Anthony d’Offay Gallery. They had been shown in de Kooning’s primary market exhibition there in November 1984. It was barely six months later that Aqualung was acquired at Equilibrium, Koons’s exhibition at the scruffy and artist-run East Village gallery, International With Monument.

Two sinuous threads tie the collection together in a time zone that ranges from the last half of the 20th century to the first decade of the 21st, and serve as a powerful springboard to other more contemporary artists and critical art movements. Those, of course, are Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

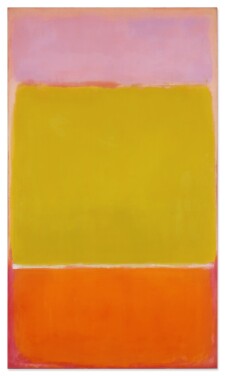

Spectacular examples from the 1950s of Franz Kline, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock combine with no fewer than five Andy Warhol paintings, dating from 1962 to 1986, to make a kind of music rarely heard in a single room.

Take for example, Jackson Pollock’s swirling black pools of motion in Number 17, 1951, executed in enamel on canvas, and imagine it with Andy Warhol’s equally iconic and arresting Nine Marilyns from 1962, the latter all the more rare with the artist’s pencil marks that guide the serial impressions of the screen goddess still visible. Both paintings were acquired privately in the mid 1990s. It again affirms the thoughtful and determined approach to searching out and acquiring targeted masterworks that underpins the collection.

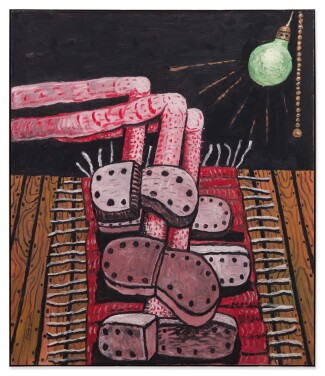

How do you characterise a collection rich in Minimalism and stellar examples from the feather-touch likes of Agnes Martin, Brice Marden and Robert Ryman to a single and spectacular figurative work by Philip Guston (Strong Light from 1976, which starred in Kirk Varnadoe’s High & Low exhibition at MoMA) or for that matter, the exuberant, colour-charged and massive Cy Twombly suite of peonies, Untitled from 2007, in acrylic and crayon that ranges over six conjoined wood panels?

Add to that exhilarating mix the magisterial abstraction of Mark Rothko’s No. 7 from 1951 and Gerhard Richter’s Greenland-sited Seestück (Seascape) from 1975, and what can you say? It is simply breathless.