Li Jin at the Aman Summer Palace October, 2012.

NEW YORK - For many non-Chinese, tofu and Chinese ink painting (shuimo, literally, water ink) are both acquired tastes. Like tofu, a staple of Chinese food known for its plain taste and ability to absorb flavors from other ingredients, shuimo painting is simple looking but capable of magical transformation into endless artistic possibilities. Sotheby’s upcoming Shuimo / Water Ink: Chinese Contemporary Ink Paintings selling exhibition, the first dedicated sale of its kind, illustrates how contemporary artists are employing this quintessentially Chinese medium to re-imagine time-honored landscape paintings.

For the better part of the twentieth century, Chinese art history read like shouting matches among various camps: preservationists of painting in traditional styles (controversially nicknamed “National Painting”), champions of Western-influenced oil painting (dubbed “Western Painting”), advocates for drawing from the Western concept and technique while staying within the framework of ink painting, and proponents of practicing oil painting but incorporating characteristics of ink painting. They had engaged in debates about everything from modernization of ink painting, art academy curricula, virtue of Western methodologies (such as linear perspective, chiaroscuro and studies of anatomy) to the application of Chinese or Western art theories. These debates continue to this day, with a recent one embroiling painter Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010) in the 1980s.

In Maoist China, the dominance of Socialist Realism favored oil painting at the expense of ink painting, with the latter being relegated to feudal elitism. After the Cultural Revolution came to an end in 1976, for a period of time oil painting, sculpture, photography, video and other new forms of expressions stole the thunder from ink painting, at least as far as contemporary Chinese art was known in the international art world. When one visited international art fairs, biennials, museum shows and auction sales, contemporary ink paintings in the traditional vein were clearly not the main stream.

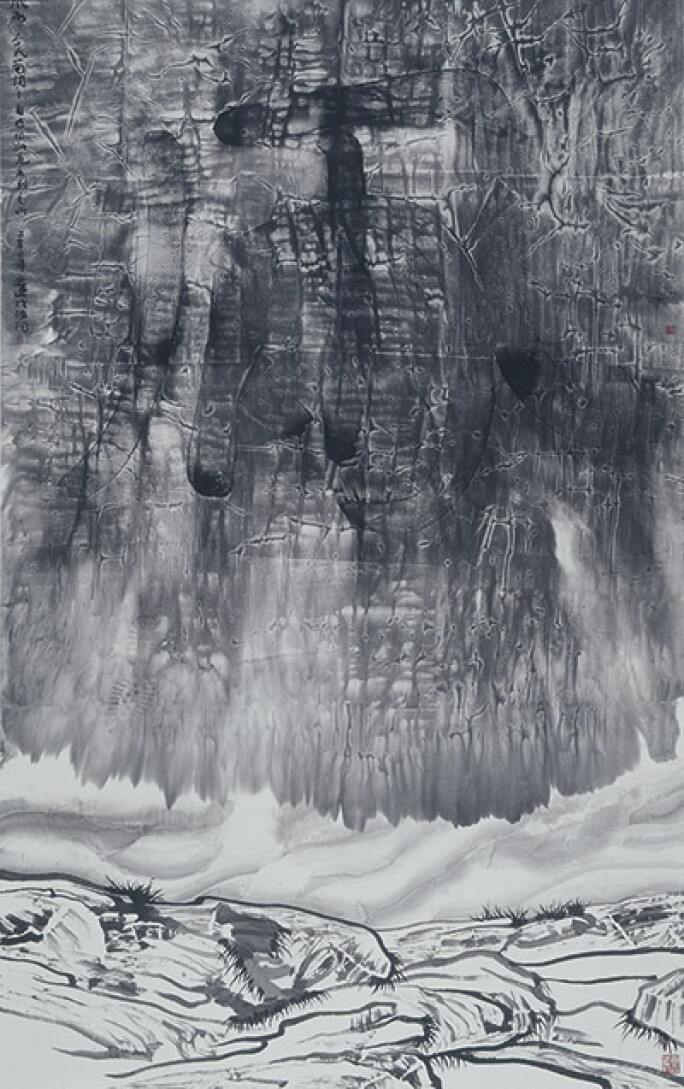

Gu Wenda's Gu's Phrase - Study from Nature Series #5, Wind & Rain.

But in recent years, whenever I strolled through the major museums in Beijing and Shanghai, I often found contemporary ink painters not on my radar screen holding court, drawing throngs of visitors to their solo shows. In the wake of the art exchange and art fund fevers that have engulfed different cities in China since 2009, many contemporary artworks that artificially achieved an “IPO pop” through reportedly manipulated sales process were done in traditional water-ink. So I knew as an art practice, shuimo still has its following in contemporary China. In fact, a few recent exhibitions represented attempts to re-introduce it to the international audience of contemporary Chinese art: Modern Chinese Ink Paintings and Calligraphy (2012) at the British Museum; Ink: The Art of China at the Saatchi Gallery (2012); Revolutionary Ink: The Art of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society, New York (2012); and, though focusing on theme rather than medium, Shanshui: Poetry Without Sound (2011) at The Museum of Art Lucerne, drawing from Uli Sigg’s contemporary Chinese art collection.

Traditional Chinese art theories divided the subject matters of ink painting into three categories. Landscape had always been more endearing to the hearts of the Chinese literati than flowers-birds and human figures. Shanshui, the Chinese rendition for landscape, literally means, “mountain-water.” Chinese landscape painting is a vision of natural order that embodied, initially, the well-governed state, and later, scholars’ cultivated minds. Traditional Chinese landscape painting did not subscribe to the Western notion of linear perspective that we have come to know through the framework of representational art. Generally it showed depth through “three planes”: foreground, middle ground and background, sometimes containing multiple points of view. Negative space, or emptiness, plays a critical compositional role. As a result, painting mountains and rivers was not an attempt to realistically represent the external Mother Nature, but to register a state of mind.

As I looked through the works to be included in Sotheby’s sale, I could not help noticing a predominant number of paintings dedicated to the landscape theme. Why did these contemporary artists, many of them considered themselves avant-garde, return time and again to a “hackneyed” subject that their forebears had been painting for more than 1,500 years? How did they make the idyllic, tranquil landscape, which seems to be out of touch with our reality, relevant to a restless contemporary society?

Many of the artworks included in the Shuimo / Water Ink sale draw on Western techniques to enrich traditional Chinese style. For instance, Xu Lei (b. 1963) divided his Rock Island (2012) into two contrasting components of equal size: the top part is covered by pale blue wash, while the bottom part is enveloped in dark navy ocean. In his depiction of the clouds and water, his application of color and brushwork was distinctively more in line with the Western style watercolor than Chinese ink painting where colors were typically subordinate to outlines and tonal variation. At the same time, the island-rock submerged under the water was painted with a style demonstrating Xu’s virtuosity of the classical ink painting techniques. As a student at the Nanjing Art Academy, Xu studied and copied works by Yuan master Huang Gongwang (1269-1354) and Ming scholar-painter Shen Zhou (1427-1509).

Xu Lei’s Rock Island, part of the Shuimo / Water Ink selling exhibition.

Gu Wenda (b. 1955), whose signature style involves writing decomposed, oversized pseudo Chinese characters in different shadings of black ink, imbues his landscape painting with the same drama of monumentality. His Study of Nature No. 6: Storm (2005) compositionally alludes to the Northern Song painter Fan Kuan’s Traveling Along Streams and Mountains (ca. 1000) and follows the “three planes” theory that had dominated the traditional ink landscape paintings in vertical format. Combining the intrinsic abstract potential of the Chinese ink and brushwork and the Modernist abstraction, Gu embedded a self-styled Chinese character within the mountain ridges as if to break down the artificial contrast between culture (namely, man-made language) and nature (namely, mountain). After all, isn’t the convention of depicting nature in a painting in itself a cultural construct?

In classical China, the Zen (Chan) painting tradition had developed its own abstract tendencies that predated the abstraction movement in the West. In Qin Feng (b. 1961)’s Desire, Landscape 007, an asymmetrical circular motion, drawn with splashing ink, takes the center stage of the painting, while sketchy mountains and water outlined in pale ink and by light brush strokes make up the lower part of the composition. While the Zen concept of enlightenment normally associates a circle with emptiness and transcendence of desires, this cipher ironically refers back to a landscape that is full of desires and energies.

Qin Feng's Desire, Landscape 007.

Traditional Chinese scholarly art emphasized lineage. Studying and copying masters’ works were necessary foundations for artistic creations. Such heritage took on an additional meaning for Li Xiaoke (b. 1944), who during the Cultural Revolution studied under his father Li Keran (1907-1989). Li Keran was pivotal in incorporating Western techniques (such as rendition of light) to illuminate his tradition-rooted ink paintings. Li Xiaoke’s Raining in Huizhou (2012) and Homeland in Ink (2009) pay tribute to his father’s signature style by using close juxtaposition and contrast of dark and light strokes and repetition of pictorial motifs such as village houses. To break out intense layers of ink brushstrokes, he introduced a dramatic white stream cutting through the page first horizontally and then vertically, reminiscent of some of his father’s landscape compositions.

Li Xiaoke's Homeland In Ink.

Scholars’ rocks have not only graced Chinese literati’s gardens and studios, they have also embodied miniature versions of the landscape of the mind. Cai Xiaosong’s (1964) Echoes of Civilization series drew from classical pictorial idioms of rocks by old masters such as Wu Bin (ca. 1568-1626), but introduced three-dimensionality by creating contoured shadows and had some of them mounted between Plexiglas. Similar three-dimensional renditions can be found in Tai Xiangzhou’s (b. 1968) Tai Hu Rock at the Dragon Fairy Studio (2012), as well as Zeng Xiaojun’s (b. 1954) Wild Spirit Screen (2012), which depicts the gnarled root complex of a camphor tree.

Also look for a piece from Zhu Wei’s (b. 1966) Ink and Wash Research Lecture Series (2012): a semi-abstract two-dimensional yellow rock is set against an expanse of red curtain. Known for his application of fine-line (gongbi) painting style associated with the imperial court and his love of rock 'n' roll music, Zhu Wei started his Ink and Wash Research Lecture Series with an expressionless, thick-lipped man in Mao suit against impenetrable, patterned red curtain or ocean waves. Later, as Zhu continued to develop this series, he replaced scholar’s rocks for the human figures. Perhaps the combination of red and yellow is more than a reference to the colors of China’s national flag—it is also a tribute to the auspicious colors a rooted in the Chinese psyche. Zhu once commented that he was an outsider to the contention between the contemporary (oil) painters and the ink painters and felt marginalized by both groups. The positioning of an enigmatic rock in Ink and Wash Research Lecture Series seems to reflect the artist’s pictorial reflection on the position of ink painting in contemporary Chinese art history.

Cai Xiaosong, Echoes of Civilization: After Wu Bin's Rock and Bryce Canyon (2012).

Many Chinese grew up reciting a line by Tang Dynasty Du Fu (b. 712): “Country is ruined, but mountains and rivers remain.” The poet’s life paralleled the fortune of his country as both were devastated by the An Lushan Rebellion of 755. Despite the historical atrocity, the strength of the nature endured. Similarly, despite the historical disruption, the return of ink painting and its favorite theme—landscape—is a poignant reminder of a popular Chinese expression, roughly based on Lu You’s (1125-1210) poem, that: “Doubt there is no path at the end of the mountains and water, / After shady willow, bright flowers, a new village jumps into my sight.” This is the Chinese version of “[e]very cloud has a silver lining.” Returning to the timeless landscape means more than returning to the Mother Nature. For the Chinese artists, it also allows them to take comfort from their culture’s deeply rooted healing power. That resilience, just like the tradition and regeneration of ink painting itself, yields new possibilities.

Shuimo / Water Ink: Chinese Contemporary Ink Paintings

Curated by Mee-Seen Loong

On view at Sotheby’s New York

March 14-28, 2013