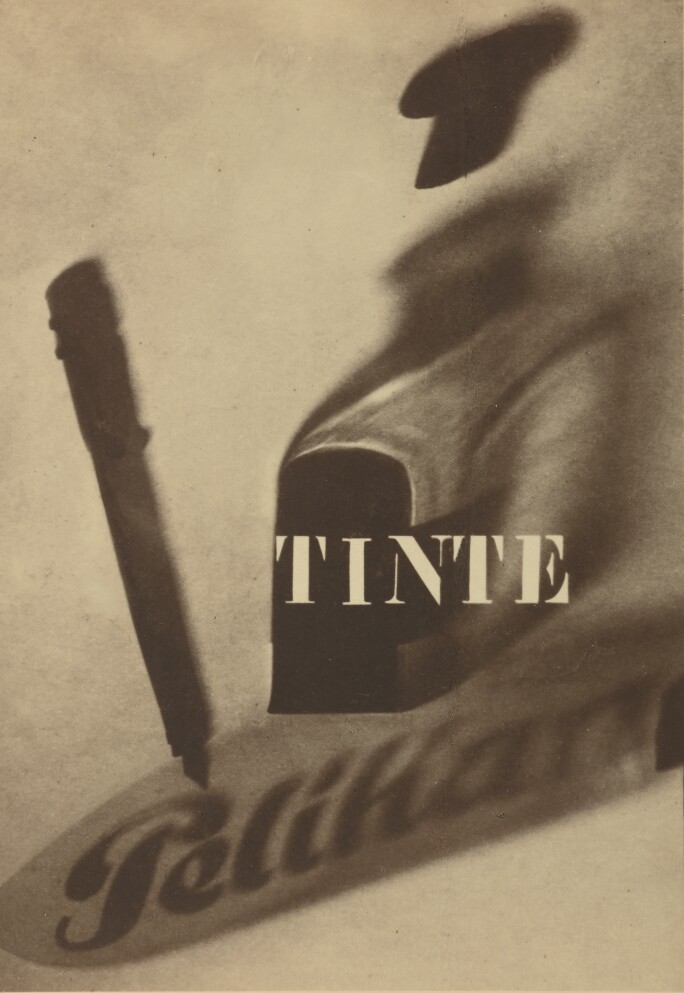

In the world of photography, Manfred Heiting is known as a man with a mission. Much more than a collector, he is a researcher, editor and educator with an encyclopedic knowledge of late 19th and 20th century images and photobooks, who, in his own words, wants to teach the world to “learn how to see.” The German collector was in the headlines last year when the Malibu wildfires claimed not only his home, but also an extensive portion of his private collection of photographs and photobooks as well as his collections of cameras, instruments, posters, ceramics and other works of art. Despite the tragedy and enormous loss, Heiting is focused on the future. He is busy lending integral support to several institutional educational programs he initiated and with his publisher Gerhard Steidl he plans to continue his series of books, which offer comprehensive documentations of individual countries' histories of photo publications. This spring, two photographs from his collection — El Lissitzky’s Pelikan Tinte and Ansel Adams’ Picket Fence — will appear in Sotheby’s upcoming Photographs auction (5 April, New York). Ahead of the auction, Heiting spoke to us about how his passion for photography developed, his time working with Ansel Adams, and more.

You worked at Polaroid for many years. Is that how you first became interested in photography?

Yes, I joined Polaroid Corporation as Art Director in 1966. Soon after, I met Ansel Adams who was at the time our “in-house” photographer. I didn’t know who he was – just that he was working for the company. Over time, I became quite aware of his importance and fame, but as Art Director I was more interested in his craft and used his images frequently for our camera and film instructions, but, not necessarily in a way that he would have liked: I often cropped parts. Once when we both were in Cambridge, I was summoned to him. He told me, “if I make a print of an image, young man, it is what it is – and you will use it the way I want it – not the way you want it”. So, I learned then and there to respect the photographic print and all its particularities and qualities. It served me well when I started to collect and I never looked only for an image, but rather for the “object” print – always the best print I could find. Of course, I also missed photographs because I could not find a “perfect” print, or the photographer made only one for a book or magazine.

What is your first collecting memory? Or the first work you remember purchasing as part of a collection?

In the beginning, I didn’t consider it collecting. I just liked Ansel Adams’ work and it was more for office decoration. I had seen his photograph Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. I really wanted to own a print or wanted to have one for my office, which was at the International Division in Amsterdam. I asked Ansel for a print. I got both a print and an invoice: $350, which was a lot. I only made $900 a month at the time. But I also did not like the white border around it – why would I need to make a frame with 20% of white space . . . all I wanted was the picture? So, I cut it off to fit one of the standard plastic box frames popular at the time. Years later, and after an enormous increase in value of the photograph, I realized how stupid that was. I went to Ansel, explained what I’d done and asked if he could sign the print on the back – and thankfully he did. This print is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Ansel Adams’ photograph Picket Fence will appear in Sotheby’s upcoming Photographs auction. What first appealed to you about that image?

I first saw Picket Fence at the home of Beaumont Newhall in Santa Fe, whom I interviewed for the German Photographic Society. The print looked at first like a Polaroid print. It was not, but suddenly the size mattered in an inverse equation. I also was attracted by its abstraction and simplicity — and by its smallness. I did not dare to ask . . . but only two years later I was fortunate to acquire it from Harry Lunn (who bought Beaumont’s collection). At the time I didn’t know that it was the only known print of this image.

You’ve owned two prints of El Lissitzky’s Pelikan Tinte. There are only a handful of prints of the image in existence. One print you’ve placed with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Now, the other will come to auction. What about this image drove you to collect it twice?

You have to take a helicopter view of advertising, design and photography and appreciate that I am a graphic designer. I also love all aspect of the Bauhaus and what came out of it in architecture, graphic and interior design, photography and art in general. Most importantly there was Moholy-Nagy, but Piet Zwart and El Lissitzky were comrades in arms. They were the most influential, creative geniuses of that period. They were brilliant in architecture, graphic design and every conceivable form of expression, and yes, also in photography.

There are two well-known images by Lissitzky: The Constructor and Pelikan Tinte, which is the design for a poster for the German ink company Pelikan. Although the poster was not realized, the design of it was in every advertising art, avant-garde and photography publication in the 1920s and 1930s. The Constructor is a collage and the original is in a museum in Moscow. The image was also widely reproduced, but all prints we know of The Constructor are reproductions from the original collage, whereas Pelikan Tinte is “it”! It is very intriguing though we do not know exactly how he made it. As a designer I liked its synthesis of visual elements. It was included in Foto-Auge, the famous 1929 book by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold. The print which I’m offering at Sotheby’s this spring I acquired at auction in 1991. In my opinion, it is the most pristine print possible. It is strong in its mono-chrome color. The surface quality is flawless. I always considered this print as one of the five most important ones in my collection. In 2005 I was offered another print of this image in a slightly different color: it was the one used by Tschichold in Foto-Auge. That print is now part of my collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

You said that you collect for the quality of the print. What is it about the quality of the print that’s so important, more so even than the image?

The image creates the attraction. But when it comes to me wanting to own a print of it, technical quality and condition become more significant. Ansel was also a very talented pianist and he always compared photography to music: the negative are the scores. In music, you have the scores and then you have a performance. In photography the print is the performance. The negative is not the original – it is the print made in the darkroom, and each is slightly different.

You’re also an avid photobook collector. Did your interest in books emerge simultaneously with photographs?

I collect photobooks because I am interested in historical documentation. Being born and raised in Germany I know what happens when there was a war — and what is left in the aftermath.

We can learn much more about the 20th century through the study of photo books and magazines. Photographers wanted their work to be published not just seen on a museum wall. If we listen to Ansel Adams and accept that photography is like music, the photobook is the orchestra, and you need a good orchestra to make a great photobook: design, layout, typography, text, paper, printing, binding and so on. Then it comes all together — not just printed photographs on white paper. Until the 1970s a photobook was about a subject or a theme, be it the Farm Security Administration, the Vietnam war, New York City or John F. Kennedy — certainly not just art by itself. Most photographers at the time only made about 3% or even less of their work as prints for museum, galleries or collectors, whereas the vast majority of their work is in books, magazines or for promotional purposes. In the 1990 I realized I could know much more of the work of photographers through books and magazines – because many of the great images were only published there.

Why have you decided that now is the time to sell these two photographs?

During the last 25 years my interest has been in learning how to see and help others to do the same. I was fortunate to have had many great mentors and was able to stand on the shoulders of others. Photography was very good to me and I try to give something back. Education is the most important thing we can give to our younger generations. To learn about the history of photography you have to learn with the original object at hand, not just as image on the monitor. I have initiated and helped to fund research at several European museums for students to be able to study there: they select a topic, write about it, express opinions. And I fund the publication of this research as well. Furthermore, I also believe it is important to document a country's history of photo publication “complete as originally published” that takes time and involves a number of writers and researchers. To fund all these activities, I need to sell these treasures – but I believe it’s worth it.