F rancis Bacon’s relationship with George Dyer was fraught with conflict, charged with love, blurred by alcohol, and agonisingly dysfunctional. The younger man was a living paradox: at once gang-affiliated East End petty crook, and vulnerable alcoholic craving validation and support. At the same time providing the unconcealed inspiration for the most powerful works of Bacon’s oeuvre, and then proving an insufferable hindrance to their completion and display on so many occasions. In the end, Dyer was a man consumed by his effigies: the social relevance, intellectual significance and financial comfort they afforded him completely blotted out any trace of his previous life. As a result, his eventual fall from grace was swift, unforgiving, and fatal. Bacon had other muses during his career; he certainly had other lovers, and always a wide array of friends and companions. However, none left such an indelible mark on his life and work as George Dyer.

The much propagated tale that the pair met when Dyer broke into Bacon’s house is a myth, compounded by its dramatisation in the 1998 Love is the Devil. The true location of their first meeting was perhaps even more fitting: a Soho pub. According to Bacon “George was down the far end of the bar and he came over and said ‘You all seem to be having a good time, can I buy you a drink?’’ (Francis Bacon quoted in: Michael Peppiat, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London 2008, p. 259). From that point on, Dyer became devoted to Bacon. He admired his intellect and power and was in awe of his self-confidence. He felt as if he had found a purpose, as the prominent artist’s companion.

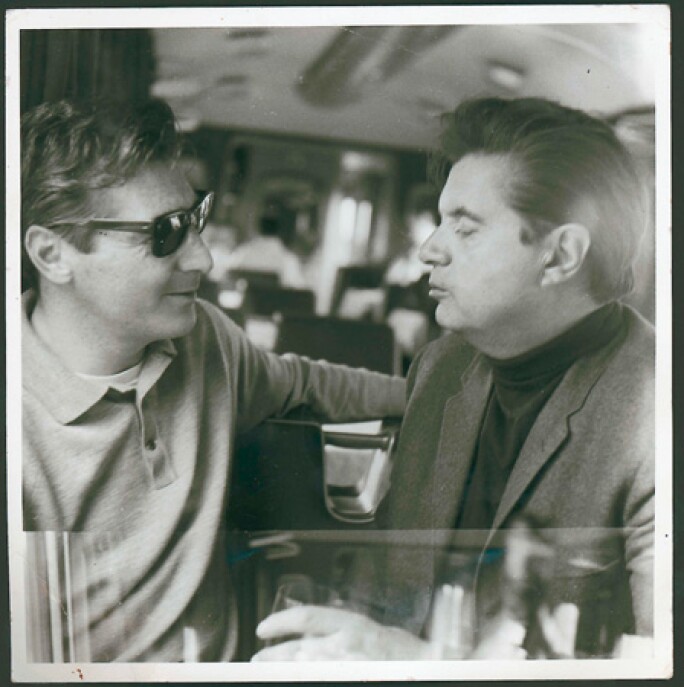

Black and white photograph of Francis Bacon and George Dyer on the Orient Express, 1965 Photos: John Deakin Collection: Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2014

From Bacon’s point of view, although himself incapable of physical harm, it is undeniable that he had a certain fascination with lawlessness and risk. He had already become acquainted with the Kray twins, the most notorious and violent gangsters in London’s history, while in Tangier, Morocco: “they were dreadful, of course, just killing people off and so on, but at least they were really different from everybody else – they were prepared to risk everything” (ibid. p. 268). It was this same sense of danger, of criminal risk, that originally attracted Bacon to Dyer. The younger man wore the Kray uniform of immaculate sombre business suits, and appeared fi t and muscular, perhaps even slightly threatening. He was born into an East End family for whom anarchy was a way of life, and when he met Bacon, around his 30th birthday, he had spent more of his life in prison than out of it. However, it very rapidly emerged that this tough exterior belied a kind and overwhelmingly vulnerable spirit, that the reasons for his incessant incarcerations were based more in incompetence than meaningful delinquency, and this facet to their attraction soon faded.

Thus Dyer fell into a new role – that of the proud muse and lovable rogue. From the mid-1960s onwards he never missed a gallery opening in London, New York, or Paris, regularly leading visitors round to proudly point out those works for which he was the unconcealed inspiration. Bacon loved his impudent art world ignorance, and the way he loudly expressed his disbelief at the vast sums exchanged for each work. Much to the artist’s delight, Dyer would slosh vintage wine into his ever-empty glass, drain the dregs from each bottle, and scoff through the aesthetic discussions that abounded. The man who Bacon dubbed ‘Sir George’ was mischievous and refreshing; the embodiment of the artist’s distrust of ‘frills’ (ibid. p. 263). Above all, he offered the artist an escape from the tortures of his over-intellectual mind.

Francis Bacon’s studio, 7 Reece Mews, London Photo: Perry Ogden Collection: Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2014

However, this was not a sustainable rapport. Even a cursory examination of Bacon’s previous relationships would reveal his tendency for masochism – pleasure was never far from pain. First was Eric Hall, who flipped between lover, patron and torturous master. Then came Peter Lacy, who threw Bacon through a glass window, causing permanent damage to his right eye, and fantasised about chaining him to a wall. Even as a teenager, Bacon was alleged to have had an affair with one of the stable boys his father paid to beat him on their Irish horse farm. In the context of these tempestuous relationships, there was a sense of inevitability about Bacon’s doting, quasi-avuncular relationship with Dyer, a sense only catalysed by Dyer’s rapid descent into increasingly destructive drinking. Even so, and despite Bacon’s best eff orts, the East Ender refused to be marginalised; he denied offers of a luxurious studio and of a place in the country – even financial settlements were spurned. Instead Dyer began to lash out. At one stage Dyer even attempted to frame the artist for drug possession in an act of bitter revenge.

These attention seeking acts only grew in gravity, indeed, by 1971 Dyer had already attempted suicide on more than one occasion foiled each time by Bacon with a stomach pump. Bacon was to be honoured with a major retrospective at the Paris Grand Palais in the autumn and, as usual, Dyer insisted that he be invited and attend the opening. Bacon almost completely ignored his companion once they arrived in Paris and occupied himself with arrangements and the press. Tragically, this ignominious irrelevance proved too much: he took an overdose of sleeping pills and was found dead in his hotel bathroom two days before the grand opening. Although Bacon stoically continued with the exhibition as normal, the death of his companion had a profound effect on the artist – probably much more profound than if he had lived. Years later Bacon said “if I’d have stayed with him rather than going to see about the exhibition, he would be here now. But I didn’t and he’s dead” (ibid. p. 265). Of course as well as missing the love of his companion, it may well have been this sense of self-blame, of guilt, that meant Dyer remained ever-present in the work of Bacon. The tragic irony was that in his hapless hopeless death, this vulnerable addict provided the artist with the masochistic punishment he couldn’t give him in life. It was this emotional flagellation that glued Dyer permanently to Bacon’s conscience and haunted his paintings. Only in his death did George Dyer finally ensure his social relevance and finally secure his immortality “in the iconography of the British face” (John Russell, Francis Bacon, London 1971, p. 163).

“A compact and chunky force of nature, with a vivid and highly unparsonical turn of phrase, he embodied a pent-up energy... a spirit of mischief, touched at times by melancholia... his wild humour, his sense of life as a gamble and the alarm system that had been bred into him from boyhood... George Dyer will live for ever in the iconography of the English face.”