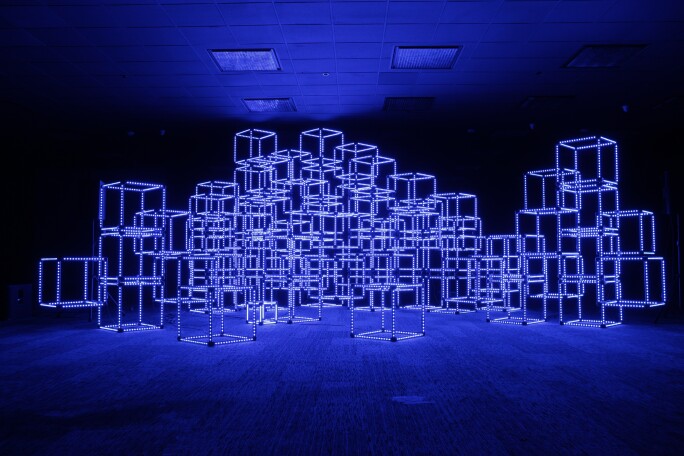

Sea of Light at South Street Seaport. © SymmetryLabs 2018

The Innovator You Need to Know: Alex Green of Symmetry Labs

Earlier this year I caught up with Alex Green, CEO and Founder of Symmetry Labs. Alex escapes definition; he is equally artist, inventor, historian, physicist, and engineer. Symmetry Labs is symbiotically complex, collapsing art and technology into monumental site-specific installations. Alex and I talked about his recent projects, the benefits of being in the Bay Area, and what’s coming up next.

Watch Video:

Symmetry Labs

Alex Green, CEO and Co-Founder of Symmetry Labs. © SymmetryLabs 2018

Thanks for joining us today, Alex. Could you tell us a little about yourself?

My parents are classical musicians and art lovers, so I grew up around orchestra, chamber music, and art galleries. In school, I was fascinated by imagination and the power of the mind to understand the world, and went on to study math and physics with a minor in jazz. I wanted to explore the intersection of technology and art, and knew this was a bigger vision than working as a solo artist.

How did Symmetry Labs start?

Symmetry Labs started as a pretty discreet idea to build an interactive, sensor-based light sculpture that could be played like an instrument and interact with an audience in real time. I was at an Amon Tobin concert in San Francisco where Tobin created this sonic landscape by marrying noise with incredible visuals, many of which were sound responsive. In that moment that I realized that technology was enabling new types of art that could change the sensory balance of experience, and engage people in ways they hadn’t been tickled before. I got together with a group of incredible engineers and we started with a chaotic jumble of welded steel cubes with LEDs on the outside. This experiment ultimately became the Sugar Cubes.

Sugar Cubes, an installation by Symmetry Labs. © SymmetryLabs 2018

Contemporary Art in America's Tech Capital

Has being based in the Bay Area helped your evolution?

We started the company in San Francisco because of the depth of engineering talent here, but the area has its strengths and weaknesses. No one can argue that a Cisco Server Rack doesn’t route internet traffic or that a self-driving car doesn’t self-drive, but if people don’t grow up believing that art matters, I wonder how you convince them of that later. For me, art is an intrinsic part of life. And while art might not serve as clear a purpose as a widget that routes traffic or a search engine, the experience of reading James Joyce, or listening to Pearlman play a Bach Sonata, can offer the hope that other people see and feel the world like you do. I think people in the Bay Area are itching for those experiences, because the scene has been so dominated by technology.

Where does the name “Symmetry Labs” come from?

I’ve always been interested in symmetry. We often solve otherwise intractable problems in physics by finding some hidden symmetry from which a solution falls. In geometric and generative mathematical based art, beauty often falls from subtle symmetries and asymmetries, even. I wanted our name to evoke both balance and complexity; the technical and the aesthetic. Symmetry Labs just felt right.

Is there one way to classify the work that you do now?

People throw “light-art” around, but I don’t think that fully describes it. Much of what interests me in art is blurring lines. I don’t want our projects to be derivative of something that came before, and I like that they are difficult to classify. Our work is a lot of different things; it’s digital art, it’s light art, it’s multi media art, it’s sound art.

Watch Video:

Sea of Light

Still of Sea of Light at South Street Seaport, New York City © SymmetryLabs 2018

Responsive Design and Site-Specific Installations

Tell me about your newest project, Sea of Light which lives down at South Street Seaport. How did it come to life?

Howard Hughes came to us with a RFP for an interactive piece that could live outside from December through March. New York in the winter is cold and dark, and the days are short, so we set out to make something bright; something that mimicked a sunset, or a sunrise, all the time. Interaction was core to the piece, and one of my favorite programmed animations was to leave the sculptures off until somebody walked by. Sometimes people immediately realized that the sculptures were responding to them, and sometimes it took a few moments for them to pass through. Once they realized what was happening, however, it was a perfect moment of surprise and delight, especially on a lonely street at night. We had displayed the Tree of Ténéré at Burning Man where people expect wild and unusual things, and it still blew the audience away. It was exciting to install a work that is so unusual into everyday life.

The programming and design of the work itself is complex. How did you make this installation?

Every time we make something interactive it’s very different, and it is usually dictated by how one is collecting the data. For Sea of Light we used thermal cameras. You have to look at the camera data, analyze it, and figure out how to accurately track humans in space. The spheres themselves are constructed of acrylic moulding, vacuum sealed to an internal armature that holds the LEDs. With each new project there are always some surprises, and that’s part of what makes the work fun and interesting.

There’s a great narrative element to your work as well…

I like the idea of connecting our installations to historical narratives because I believe that everything exists in context in modern society; what’s old is new, is new again. With Sea of Light, I began thinking about the physical Seaport itself and the use of constellations for nautical navigation. In particular, I was reading the story of Cassiopeia, a constellation relied upon by nearly every seafaring society in the world. I thought it would be cool to represent that story in such a historic place in New York City, and we set out to make something evocative of a star-cluster on the ground.

For the Tree of Ténéré, I read different stories of famous trees around the world and stumbled upon a tale about the most remote tree on earth. As it goes, there wasn’t a tree for hundreds of miles, and by all accounts when people encountered the tree in the Sahara it was a mystical experience. The real tragedy, however, was its demise, when it was killed by a drunk driver in the 1970s. With this installation, we were trying to evoke this beautiful phoenix-like rebirth in the desert on Black Rock, and I think we accomplished that.

Watch Video:

Still of Tree of Ténéré at Burning Man, Black Rock City. © SymmetryLabs 2018

Your work takes many forms, from the inorganic cube to the organic tree. How do you pick your fundamental form?

That’s a great question. The cubes represent something digital, quantized, or other-worldly that is more fundamental and simplistic. They are a minimal geometric form, and yet we can build from them. But the departure to more organic forms was quite intentional. I suspected that the medium of light might be even more powerful if we augmented prototypical forms like “tree” or “plant.” There is meaning to be had in registering a familiar object, but experience it as something far more complex. As we animate across the surfaces of our installations, we are able to tell all of these stories that hit a few different parts of your brain in a way that is very cool.

A New Era of Arts Patronage

How does patronage play a part in your practice?

We’ve been fortunate to receive support from the tech world and increasingly from art collectors as well. It will be interesting to see who our major patrons are moving forward, and I think there’s a learning curve. Symmetry Labs exists in a new and tough-to-define field that’s trying to integrate new media and technology into art. There is a lot of “flash-bang-boom” stuff that’s big and impressive, but maybe not that profound. We are not just trying to build big, impressive stuff. We want to build beautiful, meaningful things that tell a little piece of the story about

the “now.”

Speaking of the “now,” what’s next?

Stein Erik Hagen, a major Norwegian collector just commissioned a new piece for the city of Oslo, so that is one of our major focuses. Inspired by the Tree of Ténéré, the installation is a new kind of tree that will hopefully go in the fall of this year. I think there’s something about Scandinavia that invites work that is both deeply natural and utterly fantastic; the environment is beautiful, but also very extreme. Also it’s a great place to use light as the primary medium because it is dark for so much of the year. I think it will work very well there.

What, do you want people to take away from your work?

A sense of wonder and unwritten, unseen possibility.