1. Keith Haring’s first introduction to art came through his father, who drew cartoons and taught his son many of his techniques. Haring initially didn’t see the correlation with fine art, however, once saying of his early cartooning, “In my mind, though, there was a separation between cartooning and being an ‘artist’…”

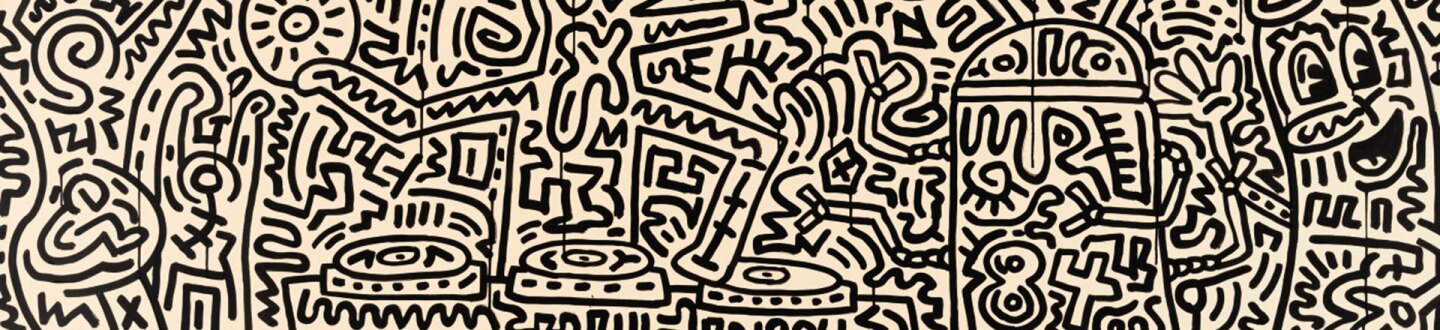

2. Three of Haring’s earliest artistic influences were Dr. Seuss, Walt Disney, and Charles M. Shultz through his Peanuts comic strip.

3. Haring had three sisters; all four Haring children have the first initial of K—Keith, Kay, Karen, and Kristen.

4. Perpetually curious about other artists and art programs, in 1976 Haring hitchhiked across the United States on a self-guided arts tour.

5. Despite being primarily known for, and working the most with, drawing, Haring spent a considerable portion of his early career experimenting with other mediums, including collage, installation, performance and video.

“Part of the reason that I’m not having trouble facing the reality of death is that it’s not a limitation, in a way. It could have happened any time, and it is going to happen sometime. If you live your life according to that, death is irrelevant.”

6. His first solo show was at the Pittsburgh Arts and Crafts Center (now the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts) in 1978. Understanding that for Pittsburgh this was a career feat, he realized that he “…wasn’t going to be satisfied with Pittsburgh anymore or the life [he] was living there.” Soon after, he relocated to New York City.

7. He was the recipient of a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts in the East Village, an award that helped facilitate his relocation.

8. While studying at the School of Visual Arts, he was able to work with and befriend numerous artists who would help shape his iconic style; further, he was able to study with premier artists who were professors at the school, including Keith Sonnier and Joseph Kosuth.

9. Spray paint graffiti, which can be seen all over New York City, had a profound influence on Haring’s early stylistic development. He was inspired both by its originality and spontaneity, as well as the calligraphic traits within artist “tags.”

"…the ‘subway drawings’ started to backfire, because everyone was stealing the pieces. I’d go down and draw in the subway, and two hours later every piece would be gone. They were turning up for sale."

10. After moving to New York City, Haring noticed that many of the advertisement boards in the subway were left blank (after one ad had been removed, and the space was awaiting a new poster). These would become the support for his “subway drawings.”

11. Once he began producing his “subway drawings,” made primarily with white chalk, his practice became prolific; he ultimately completed hundreds between 1980 and 1985.

12. Haring’s “subway drawings” allowed him to engage with his audience in an incredibly unique way. Recalling the time spent working in the subway he said, “I was learning, watching people’s reactions and interactions with the drawings…Having this incredible feedback from people, which is one of the main things that kept me going so long, was the participation of the people that were watching me and the kinds of comments and questions and observations that were coming from every range of person you could imagine…"

13. As Haring’s career progressed, he came to the point where he wanted to sell, and support himself with, his work so he could focus on creating new work full time. This led him to join the Tony Shafrazi Gallery.

14. The artist's first solo show at Shafrazi’s gallery marked his official arrival into the art world mainstream; the show was a critical success, was attended by hundreds of people, and garnered a large volume of media attention.

15. Haring’s increasing fame and popularity in the 1980s had a distinct effect on his working manner, specifically his “subway drawings.” As they became less anonymous, he recalled, “…the ‘subway drawings’ started to backfire, because everyone was stealing the pieces. I’d go down and draw in the subway, and two hours later every piece would be gone. They were turning up for sale.”

16. Throughout his career, he was frequently arrested or ticketed for vandalism. His increasing celebrity in the 1980s, however, helped minimize repercussions. For instance, he was arrested shortly after completing his now iconic Crack is Wack mural in Harlem, and faced up to one year in jail. The work, however, had become an overnight sensation, and after the Post ran a story on Haring’s arrest the community, media, and city came to his defense. He was ultimately only fined $100.

17. Haring opened his famed Pop Shop in 1986, which was a retail store that sold various forms of merchandise, from T-shirts to toys to posters, bearing images of his work. Describing the impetus for the store Haring said, “My work was starting to become more expensive and more popular within the art market. Those prices meant that only people who could afford big art prices could have access to the work. The Pop Shop [made] it accessible.”

18. The mass appeal and accessibility to Haring’s work often had an adverse effect on the art world elite’s critical reception of his art, namely among critics and curators. He largely chalked this up to the fact that he was able to essentially bypass the “proper channels” of the art world, (and, thus, those same critics and curators), and go directly to his audience and the public.

19. Haring was involved with numerous charities and causes, particularly those that involved children. He frequently held drawing workshops, both within schools and at museums, for children around the world. Some of the workshops were held in such places as Tokyo, London, and, of course, New York City.

20. Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, and the following year he founded the Keith Haring Foundation. One of the key objectives of the Foundation was, and still is, to provide funding and support to AIDS research and charities.

21. Though he was deeply aware of the effects of his medical condition, as many of his friends and colleagues had perished from the disease already by the late 1980s, Haring maintained a philosophical outlook on his life up until the end, saying “Part of the reason that I’m not having trouble facing the reality of death is that it’s not a limitation, in a way. It could have happened any time, and it is going to happen sometime. If you live your life according to that, death is irrelevant.”