- 7

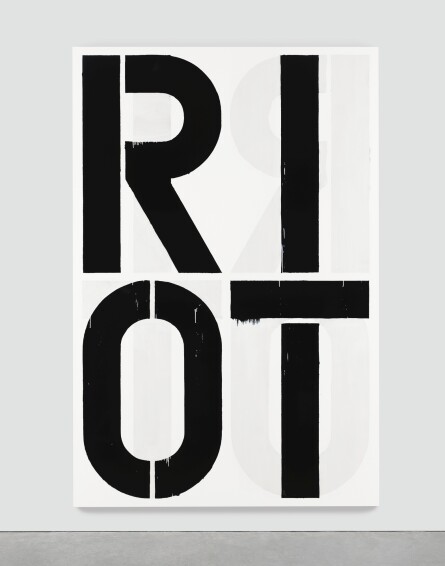

Christopher Wool

Description

- Christopher Wool

- Untitled (RIOT)

- signed, dated 1990 and numbered W14 on the reverse

- enamel on aluminum

- 108 x 72 in. 274.3 x 182.9 cm.

Provenance

Acquired by the present owner from the above in June 1991

Exhibited

Santa Monica, Luhring Augustine Hetzler, Larry Clark, Robert Gober, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Cady Noland, Richard Prince, Charles Ray, Cindy Sherman, Christopher Wool, September - October 1991

Los Angeles, The Museum of Contemporary Art; Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Art, Christopher Wool, July 1998 - January 1999, p. 61, illustrated, p. 62, illustrated (in installation at Kunsthalle Bern, 1991) and p. 112, illustrated (in installation)

Literature

Exh. Cat., Valencià, IVAM Institut Valencià d'Art Modern y los Musées de Strasbourg, Christopher Wool, 2006, p. 7, illustrated (in installation)

Hans Werner Holzwarth, ed., Christopher Wool, Cologne, 2008, p. 109, illustrated (in installation)

Exh. Cat., New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (and travelling), Christopher Wool, 2013, p. 93, illustrated (in installation at Kunsthalle Bern, 1991)

Catalogue Note

The oft-recounted story of the moment Christopher Wool was moved to create his first word painting is something close to a New York myth. It’s the kind of account that perfectly conveys the magic of the city: in 1987, while walking the streets of his Lower East Side neighborhood, Wool encountered a new, yet graffitied, white truck. Scrawled across its side was a tag reading, “SEX LUV” and the artist was so affected by the sight, he returned to his studio to create his own painterly version. This initial rendering of S-E-X and L-U-V laid the groundwork for what would become his signature technique—large black letters, placed vertically over one another and stenciled upon a smooth white background. Wool began this series in 1987 by painting prominent stenciled black capital letters on aluminum surfaces, reveling in their elusive quality and ambiguity; associated with both the punk poetics of the downtown scene in the early 1990s alongside the increase in postmodern critical thinking, Wool’s paintings investigate the limitations of language as descriptive signifiers, challenging the legibility and objectivity of language by its visual capacity for incessant re-interpretation. His dispossessed language is no less abstract than his formal mark-making; with Untitled (Riot), the claustrophobic, broken letters are enlarged and confined within the immense metal field spanning nine feet in height. Like street signs or tabloid headlines, this word is both matter-of-fact in its presence and manifestly urban. Wool’s street-smart approach to art is also like that of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who similarly found inspiration in New York’s periphery. There in the fringe’s unfashionable neighborhoods, both artists assembled and defined their own unique vocabularies. Basquiat, for his part, developed an engaged and personalized style of pop culture symbolism; Wool, meanwhile, discovered the promising possibilities of linguistic abstraction. His use of demotic misspelling, symmetrically stenciled words and unexpected breaks in text are the tangible products of an urban landscape.

The painterly composition is minimal and the individual letters have been reduced to a bipolar, stenciled schematic. Whereas the execution of the work achieves the perfection of Minimalist reduction on the one hand, on the other it includes overt suggestion of its handmade manufacture, with the irregular outline, smudges and drips heavily in evidence. Through his text paintings Wool interrogates not only the definitions of subject matter, conceptual content, and creative authorship in painting, but also demonstrably exhibits a love of the act of creation, insistently leaving remnants of the process of its making, such as the luscious drips of ink-like paint in the present work, to designate the hand of the artist. Wool is interested in the way that text can function as image, harnessing the pictorial qualities of his stenciled letters to accentuate their status as shapes and de-naturalize their communicative utility. In arranging the word RIOT into four quadrants, Wool simultaneously reveals the frontal clarity of this short, powerful word, while making efforts toward destabilizing its legibility in its grid-like composition. As explained by Katherine Brinson, “He has long been fascinated by the way words function when removed from the quiet authority of the page and exposed to the cacophony of the city, whether through the blaring incantations of billboards and commercial signage or the illicit interventions of graffiti artists. But with their velvety white grounds and stylized letters rendered in dense, sign painter’s enamel that pooled and dripped within the stencils, the word paintings have a resolute material presence that transcends the graphic.” (Katherine Brinson in Exh. Cat., New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (and travelling), Christopher Wool, 2013, p. 40)

Dating back to the Analytic Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque before the First World War that incorporated collaged elements of newspaper headlines, typography became an integral part of Futurism, Constructivism and Bauhaus design. During the 1950s, when galleries were dominated by Abstract Expressionism, Jasper Johns used stencils in his work to counter the outpourings of emotion among his fellow painters. Referencing Duchamp and Dada, Johns was interested in stencils because of their ready-made status - when used in paintings, they challenged the authenticity of the personal brushstroke. Even Francis Bacon would come to incorporate Letraset typography in his paintings to address questions of Saussurian semiotics, the dynamics of sign systems, and methods of communication. Furthermore, Concrete poetry of the 1960s and early 1970s abandoned grammar, syntax and punctuation to break words into apparently arbitrary units. However, by focusing more on process rather than subject matter, the act of painting itself became Wool's primary subject.

In every way exemplary of Wool’s specialized approach to painting, Untitled (Riot) presents the viewer with a formally engaging and intellectually rigorous artistic experience. As one of Wool's earliest and most legendary word paintings, the present work occupies a place in the history of art—it is through works such as this that Wool ultimately advanced the project of painting in the face of postmodern skepticism. Perhaps curator Madeleine Grynsztejn phrased it best when she wrote, “Wool deliberately choreographs a collision between different components of language—grammatical, semantic, visual, imaginary and spoken—that conveys an emotional magnitude beyond the range of everyday speech and closer in spirit to the true proportions of Wool’s subject: the inherent inefficacy and near-constant failure of language.” (Exh. Cat., Los Angeles, The Museum of Contemporary Art (and travelling), Christopher Wool, 1998, p. 267) With the present work, Wool did not just spark a riot—he caused a revolution.