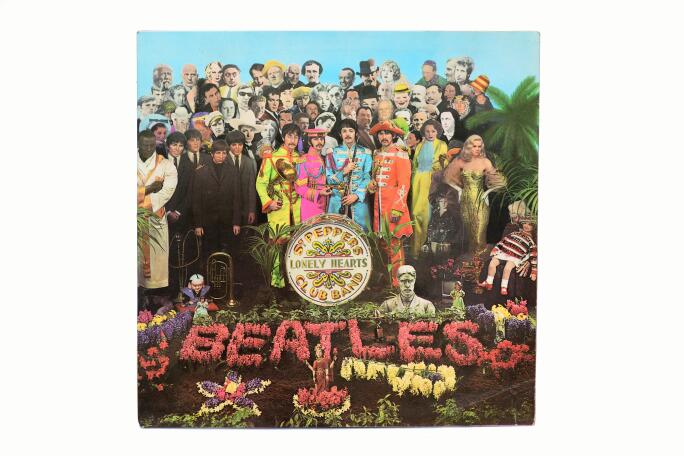

F ifty years ago, in 1968, the Beatles faced the task of following up on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the album that Kenneth Tynan, the theatre critic at The Times in London, had described as “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilisation”. The sprawling 30-track double album that emerged was simply titled The Beatles. But no one ever calls it that. The name we do have for it is thanks to Richard Hamilton. The British artist was himself charged with following up on a titanic achievement – Peter Blake and Jann Haworth’s cover for Sgt Pepper. His solution was simple: to leave the cover almost completely blank; a minimal, conceptual response to the explosion of imagery and colour in Blake and Haworth’s design. Hence, in the popular imagination, The Beatles became the “White Album”.

The history behind the cover’s design, like its predecessor, begins with the art dealer Robert Fraser. The Beatles, and their rivals the Rolling Stones, were part of the Swinging London orbit around the dealer, who was known, much to his chagrin, as Groovy Bob. It was Fraser who advised Paul McCartney to bring in a fine artist for Sgt. Pepper, and Blake and Howarth’s peculiarly nostalgic British Pop-art sensibility chimed perfectly with the Beatles’ musical concept for the album. When McCartney approached him again, he suggested Hamilton. Few artists were as influential in British contemporary culture at that time. He had defined Pop art as a leading figure in the Independent Group in the late 1950s – “popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business”. He was also, by that stage, a founding father of conceptualism in Britain.

It’s unsurprising, then, that his idea for the album artwork would bear many of the hallmarks of conceptual art: stripped back, witty, mindful of the cultural context and audience of the work, foregrounding its means of production and distribution. Hamilton remembered, in an interview with Pete Stern and Alex Turnbull just before his death in 2011, that his idea for the album reflected his “habit to look for the opposite”. He suggested to McCartney that “Sgt. Pepper’s cover was so filled with activity that it might be nice to have a completely clean sheet and just do a white cover”. It was also Hamilton who proposed they call the album simply The Beatles.

He had the idea of numbering each copy, “to create the ironic situation of a numbered edition of something like 5 million copies”. This was adopted, and the first 2 million copies were machine-stamped. It is a brilliant conceit: turning a mass-produced commodity, by one of the globe’s most popular bands, into a limited edition, so that each individual copy of the White Album was a unique work. It is also a knowing Pop-art strategy, bridging high and low culture, and perhaps a sardonic nod to the Beatles’ avant-garde pretensions.

That Hamilton’s idea was accepted is testament to the sway that the Beatles had with their record company: “They were so powerful with EMI that they could do whatever they liked,” Hamilton said. But there was one compromise. “They were able to get them to print the thing exactly as I wanted except that they put the title The Beatles, of course, blind embossed, which I wouldn’t have done,” he said. McCartney claimed responsibility for this element of the design.

Hamilton’s involvement wasn’t limited to the cover. He admitted to feeling a bit “a bit guilty at putting their double album under plain wrappers” and “suggested it could be jazzed up with a large edition print”. This resulted in the folded poster that was included in all the initial editions of the album. Again, Hamilton’s “habit to look for the opposite” was evident: where the cover was blank, the poster teemed with imagery, of a very personal nature. He asked the Beatles to provide unseen and intimate photographs – McCartney coordinated the Beatles’ efforts and Hamilton received three tea-chests full.

Hamilton composed a brilliant collage, a process a rapt McCartney witnessed over the course of a week at the artist’s studio in Highgate, north London. McCartney remembered “a very German interior to the studio, very Bauhaus, very 60s modern”, and was particularly awed by the moment at the end where Hamilton applied five small white pieces of paper to provide negative space among the jostling photographs. “It was beautiful. That was cool. For me that was a great lesson that I was getting from the hands of someone like Richard Hamilton, a whole week of his thoughts. No mean teacher, man!”

The poster was reproduced as an edition of digital prints in 2007, one of which is in the Tate Collection. The edition size was 80; just a little smaller than that for the album with which the poster was first included.

The 50th anniversary reissue of the White Album is out now on Apple Corps Ltd/Capitol/Ume.