T his February, when Hedi Slimane posted a photo he’d taken of Alan Vega in New York in 2004 on Instagram, he was not only acknowledging an iconoclastic artist but also trailing Celine’s fall/winter menswear collection. The long-sleeve and sleeveless tees that appeared on the Paris runway were emblazoned with images from Vega’s “Ransom Note” series of collages, circa 1974 – words (“deadly wait,” “all-star,” “glory”) snipped from newspapers that when put together are semantically blank, but have a rawness and immediacy that makes a different kind of sense.

Under Slimane’s custodianship, Celine, the presenting partner of Sotheby’s New York Sales this May, is a serious supporter of art and artists, making Vega a fitting subject. Vega is widely celebrated as one half of Suicide, the radically minimalist, electronic proto-punk band whose debut album of 1977 sends seismic waves to the future still. Though his original creative path was visual art – he studied at Brooklyn College under Ad Reinhardt, the black-on-black conceptual artist – and he pursued it until his death in 2016, that practice is less well known today.

“Every day, I’m a different person. I’m in a different place, our world is different.”

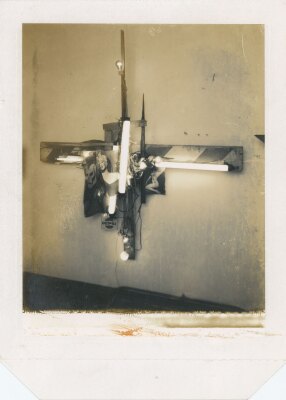

As with his music, Vega’s arts rests on directness and simplicity. Early on he made abstract paintings and highly detailed, Surrealist drawings with medieval war themes. Soon he pivoted to sculpture, developing the tough aesthetic that informed his show (as Alan Suicide) at OK Harris Gallery in 1971 and came to define his expression. Jumbled in piles on the floor were discarded electrical appliances, light bulbs, fluorescent tubing and strings of power leads, some of which had been plugged in. Though these assemblages owe something to the work of Robert Rauschenberg and Dan Flavin, they spoke to their time – New York was seen as a city in decay, blighted by a soaring crime rate and on the verge of bankruptcy. However, the works’ illumination was not just a literal manifestation of energy but also a symbol of hope.

These oddly poignant accumulations of electrical detritus scavenged from Manhattan’s streets became wall pieces. Vega gave them wooden cruciform bases, adding photographs he’d pulled off television and images of Mike Tyson, Marilyn Monroe and other celebrities clipped from magazines. Jared Artaud is the creative director of Saturn Strip, Ltd (home of Vega and Suicide’s intellectual property) and co-producer of a reworking of the band’s “Girl” that was used in the Celine runway show. He recalls Vega explaining that the cross is where two points meet in infinity: “Peeling that back more, you could see both the spiritual component and the cosmic component, which to me is a thread through a lot of his art and his music.”

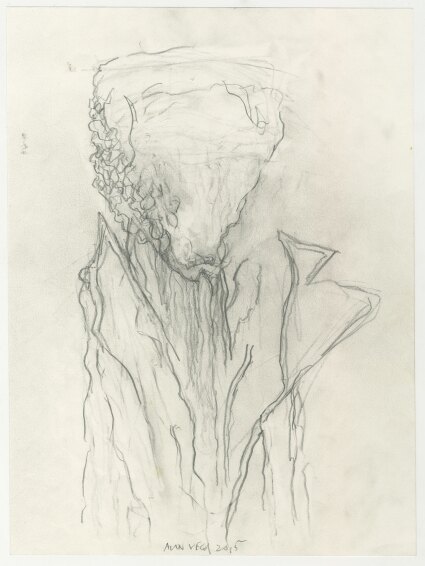

By the mid-to-late 70s, Vega’s identity as a member of Suicide had outstripped his visual art profile, and between 1983 and 2002 he didn’t exhibit at all. However, that creative drive never let up. It’s best evidenced by his journals, in which he wrote and drew constantly: alongside raw material for lyrics there are ballpoint-pen and pencil “portraits” of imaginary figures, scribbled and cross-hatched to faintly grotesque effect. As Liz Lamere, Vega’s wife of 31 years, a longtime musical collaborator and owner of Saturn Strip, explains: “He drew every single night and wrote poetry in his notebooks, like that was his religion. He was collecting things for his sculptures all the time and putting them together; he wasn’t out there looking to show because he’d rather be focused on creating. He was truly a pure artist in that regard.”

In the last few years of his life Vega returned to painting, though with a marked change. In his notebook drawings the facial features had begun to disappear, the figures transforming into self-described “spirit guides” for his transition to another realm. In his final six months he produced seven enigmatic paintings of a richness which belies that ghostly erasure. To the end, Vega’s practice evolved with his experience.

“He was constantly reinventing himself,” says Lamere, “not because he was trying to do that but because that was his natural process. As he would say, ‘Every day, I’m a different person. I’m in a different place, our world is different.’”