I n the early 20th century, Paris attracted several artists of varying nationalities. Ambitious, young, and full of ideas, the artists who arrived in the French capital flocked to the same spaces – among them, the cafés, the bars, the gardens, the nearby landscapes. The artistic community was first concentrated in Montmartre but later moved to neighborhoods such as Montparnasse as well as the 14th and 15th arrondissements. The proximity of these painters, sculptors, and writers prompted unexpected encounters. From 1900, until the early 1940s, some of the world’s most creative minds lived in constant dialogue, exchange, and even rivalry. This exciting period yielded many major masterworks of the early 1900s; the group would later be referred to as the School of Paris. Select woks from the Triumph of Color series allows us to observe the brilliance of the School of Paris movement.

A key factor in the development of the School of Paris was the vast diversity of non-French artists who made the Parisian streets their home, their studio, their inspiration. With a wide range of nationalities focusing on a few traditional subjects – mainly figure studies, still life, and landscapes – art styles collided and merged in novel ways. Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, Symbolism, Surrealism, Bauhaus, and more all mixed and mingled as artists became exposed to so many styles. A common thread in these artistic developments was abstraction. As artist engaged, their techniques began to incorporate forms and shapes divorced from realism.

Pablo Picasso is among the most prominent and earliest artists of the School of Paris. He moved to France in 1904 and was extremely productive and innovative during the years he spend there. With modernists such as Georges Braque, Joan Miró and Giorgio de Chirico joining the artistic community, Picasso’s style continued to expand and evolve; leading him to produce abstract works with surrealist character. Although it is exciting to see Picasso’s trajectory during this time, it is equally fascinating to consider how he painted prior to his move to France. For instance, his 1901 painting Iris Jaunes shows a lively bouquet of yellow irises in full bloom, neatly arranged in a beautiful blue and white vase. Picasso produced the still life in the spring of 1901, just after his first trip to Paris; he returned to Spain briefly before officially moving to the French capital.

During his first sojourn to Paris, Picasso lived a frantic life as he prepared for his legendary first exhibition in June 1901. Picasso was exposed to a significant amount of cityscapes and household arrangements; providing him inspiration for scenes of everyday life, such as Iris Juanes. He painted this work when he was only nineteen years old – his only iteration of irises according to Pierre Daix and Georges Boudaille. Iris juanes hung in the exhibit in France, and it was received with high critical acclaim and celebration. Given the young Spaniard’s success in Paris, it is not surprising he retuned a few years later. Not only did Picasso enjoy unrivalled recognition, he also had the opportunity to meet and engage with other gifted artists that also flocked to Paris. Perhaps the most notable partnership Picasso developed was with Georges Braque; their collaboration, starting in 1907, yielded major developments in the historic procession of modernism given their groundbreaking Cubist compositions.

Verre et raisins, executed circa 1918, is a fine example of Braque’s cubist style. Echoing Picasso’s bouquet, Braque has also chosen a quotidian scene of a glass and some grapes. Although there are only a few items in the still life composition, there is an enormous amount of dynamism on the paper. The sharp angles make the eye move from one part of the composition to another; occasionally one settles on a recognizable shape – such as the stem or the grapes or the rim of the glass – but after a few short moments the eye shifts into the dance of lines and curves. The muted colors employed by Braque arguably elevate the impact of his cubist style; the toned down color palette reflects the mundanity of the quotidian scene even more. This puts the focus on the cubist style. The present works exhibits a maze of shapes that together constitute a prime example of Braque’s cubism and of the beginning of abstraction in the School of Paris.

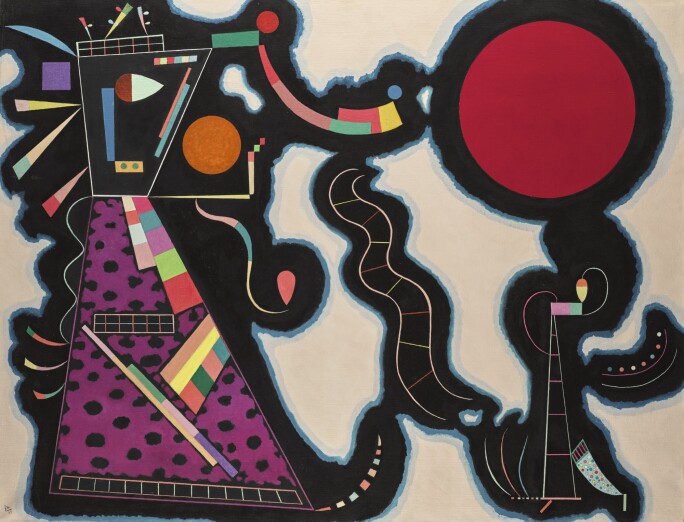

Another member of the school of Paris who expanded the visual lexicon of abstraction is Wassily Kandinsky. The Russian-born painter became renowned for his energetic, dynamic canvases. He studied law and economics and had taught at the university level for a few years. At the age of thirty, Kandinsky dedicated himself entirely to art. Once he started painting, he moved around northern Europe, eventually settling in France. He had association with the Paris scene having first visited in 1889 when he began to exhibit at various galleries, and spending his formative years in the rural outskirts near Sèvres. When Kandinsky officially moved to Paris in 1922, he began to produce some of his most well-known, ethereal paintings. Viewed from an art historical perspective, Kandinsky is often cited as being the first major artist to produce purely abstract works.

A prime example of his abstraction is Le Rond rouge, which he painted in 1939, by which point he was firmly established and occupied a prominent position in Paris. Once living in the French capital, Kandinsky was inspired by the surrealist movement, incorporating rich colors and strong geometric shapes that imbued his canvases with vitality. This work shows how Kandinsky unfailingly imbued his canvases with emotion and passion. The artist himself compared the act of painting with the creation of music. “Color is the keyboard. The eye is the hammer. The soul is the piano, with its many strings … The artist is the hand that purposefully sets the soul vibrating by means of this or that key” (W. Kandinsky, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” 1911, reprinted in C. Harrison & P. Wood, Art in Theory, 1900-1990, Oxford, 1992, p. 94). This painting evinces the above characteristics; however, Le Rond rouge – and other works from his Paris years –sets itself apart by incorporating natural forms. During this period, Kandinsky starts to include anthropomorphic biological forms in unusual colors; nevertheless, he remains devoted to abstraction. This work thus showcases the beginnings of Kandinsky’s skillful synthetization of art and nature.

Clearly, the School of Paris movement was not limited to the two-dimensional; sculpture became a medium of formalist experimentation for artists like Constantin Brancusi and Alexander Archipenko, who also inhabited the French capital during this time. Born in Russia, Archipenko joined the artist community in Paris in 1908. He moved into La Ruche, an artist’s residence in Montparnasse, where other Russian artists had already settled. By 1910 Archipenko was exhibiting with Kazimir Malevich, Georges Braque, André Derain, and others. Between 1912 and 1914, Archipenko taught at his own Art School in Paris. Archipenko was his most productive during his time in Paris surrounded by other artists. Of the subject most practiced by the School of Paris, as a sculptor, Archipenko was a master of figure studies. Most his artwork focuses on the human form.

In Walking, Archipenko composes a human figure from geometric forms in line with the Cubist style. The defined straight lines frame the figure’s legs and torso, while the curved shapes activate the sculpture and insinuate movement. The individual details of the work do not convey any discernable subject, rather they exist as abstract shapes; in other words, one has to step back and see how all the elements come together to form a human figure. Like Archipenko, many of the artists in the School of Paris were manipulating the geometric relationships of shapes to convey their subjects. In deconstructing the composition of intricate objects, the artists approached abstractions. Walking strikes a balance between Cubism and Abstraction; it stands as another prime example of the exciting developments occurring in the School of Paris during the early 1900s.

Another key feature of this work – which sets it apart from painting – is the effective use of true negative space; Walking is of particular note in its revolutionary use of negative space. According to George Heard Hamilton, “this work is the first instance in modern sculpture of the use of a hole to signify more than a void, in fact the opposite of a void, because by recalling the original volume the hole acquires a shape and structure of its own" (G. H. Hamilton, op. cit., p. 271).

The above four works discussed illustrate the impressive innovations that flourished in the Parisian streets and studios of the early 1900s. Particularly, Kandinsky and Archipenko illustrate the brilliant use of abstraction. Sotheby’s is excited to offer these works in association with other lots by School of Paris masters such as Henri Matisse (Lot 36), Chaïm Soutine (Lot 63), and Marc Chagall (Lot 62). In addition, another three excellent works by Kandinsky strongly feature in the Triumph of Color series.