J anuary 8, 1963 was a night of historic events in the artworld. While visitors to the National Gallery in Washington gazed in awe at the world’s most famous painting, those in New York squinted uncertainly at work that some wondered even qualified as art. So disparate were the exhibitions, the timing seemed ordained by the two-faced god Janus himself. In the nation’s capitol, two thousand invited guests pressed as close as they dared to the Mona Lisa, whose maiden journey across the Atlantic was prompted by First Lady Jackie Kennedy, a Francophile and art lover. In the midtown Manhattan Green Gallery, people arrived in waves, elbowing into its long narrow room to see New Work, a modestly-titled selection of paintings and sculpture by eight young artists.

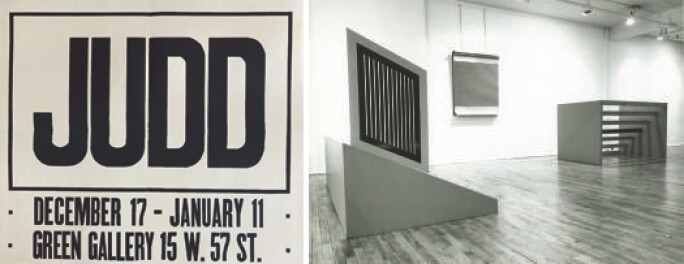

The Green occupied the top floor of an aging brownstone at 15 West Fifty-Seventh Street. By the start of 1963, midway through its third year, the Green was widely regarded as the top avant garde gallery in New York. Its director Richard Bellamy was the prescient dealer who launched the careers of Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist and Tom Wesselmann. But there was no Pop art in New Work. “New” meant artists making their debut as well as art not previously shown.

Few afficionados of cutting-edge art knew what to make of the groundbreaking work Bellamy introduced in New Work. Dan Flavin’s wall reliefs incorporated actual electric lights, and every surface of Yayoi Kusama’s cabinet sprouted stuffed canvas erections. Larry Poons’s optically dazzling canvases, and Robert Morris’s card file with entries chronicling the history of its making, flummoxed many viewers. One artist in attendance, the abstract expressionist Jack Tworkov, wrote in his journal the next day, “Went to Green Gallery, where tomorrow is yesterday, where yesterday was the beginning of ancient history.”

From the vantage point of the present, DSS 25 is a seminal work in the career of a brilliant artist who continued to work and change for more than three decades. It embodies Judd’s earliest explorations into a future he then could not see but trusted himself to find.

Nearly fifty years later, collector Lewis Winter remembered his response when he walked into New Work and saw Donald Judd’s reliefs for the first time: he wanted to own one. A merchandiser in the Seventh Avenue fashion district, Winter had grown up with the idea that tastes change, which is the very nature of fashion. The shifting nature of contemporary art did not faze him. He already owned work by Green Gallery artists Rosenquist, Wesselmann and Mark di Suvero, perspicacious purchases he made thanks to a chance encounter with the Metropolitan Museum’s new young curator, Henry Geldzahler.

A former fraternity brother of Winter’s at Wharton had befriended fellow classmate David Geldzahler at Harvard Law School. One evening early in 1961, Winter and the two lawyers went down to the Lower East Side to see David’s younger brother Henry participate in one of Oldenburg’s earliest Happenings. At a dairy dinner with the cast afterward, Winter quizzed the curator, asking: “Where should I buy current art in New York?” “Go to the Green Gallery,” Henry advised. “Bellamy has the best eye in the city. And tell him I sent you!”

For inclusion in New Work, Bellamy chose three of Judd’s recent pieces. In the middle of the oak floor he sited a construction of wooden boards linked by a pipe; and installed two wall reliefs to the right of the main gallery’s threshold. The painted wood components of all three riveted attention with a color resembling industrial underpaint, a blazing red-orange that, in Judd’s thinking, heightened awareness of edges, lines, and textures.

“I’d like this one,” Winter told Bellamy, pointing to the horizontal relief with a slot across the center. “Can’t have it.” Bellamy said. “It’s sold.” Winter then nodded at Judd’s other wall piece, a plywood panel bounded above and below by a flared cornice that intruded into the space of the room. It was unlike any relief Winter had seen before. It too was unavailable. “Don’t worry,” Bellamy assured him. “I’ll get you something,”

The “something,” then back in Judd’s studio, proved to be DSS 25, a smaller-scaled “sister” of the tripartite relief that had challenged and intrigued him in New Work. DSS 25 was the first of five related works the artist would create as he transitioned from painter to object maker in the early sixties. Judd later described it as his “first really three-dimensional relief,” but did not call it sculpture, a designation he eschewed. Neither was it a painting. The illusionary space of that genre no longer held interest for the artist, who had begun making art that interacted with the room it inhabited.

For the hand-built wood components of DSS 25 and its sister works, Judd enlisted help from his father Roy, a skilled carpenter. The artist added tooth to the wood’s grainy texture by mixing sand into the pigment for the center section. Rather than paint the framing shapes, he veneered them with pliable galvanized iron. An industrial material with personality, its dappled surface recorded the metallurgical reaction between iron and molten zinc. The curved forms themselves engaged the room’s illumination, as did their light-catching surfaces, held in place by orderly rows of nubby brads. Judd would later tell an interviewer that he had not painted the metal because it already was a color: gray.

From the vantage point of the present, DSS 25 is a seminal work in the career of a brilliant artist who continued to work and change for more than three decades. It embodies Judd’s earliest explorations into a future he then could not see but trusted himself to find. It occupies a pivotal position in the genesis of Minimalism, another label Judd spurned for his practice. Nearly a year after New Work, the Green Gallery mounted the artist’s solo debut. It included a younger sister of DSS 25 as well as the fully three-dimensional work that he would soon describe as “specific objects.”