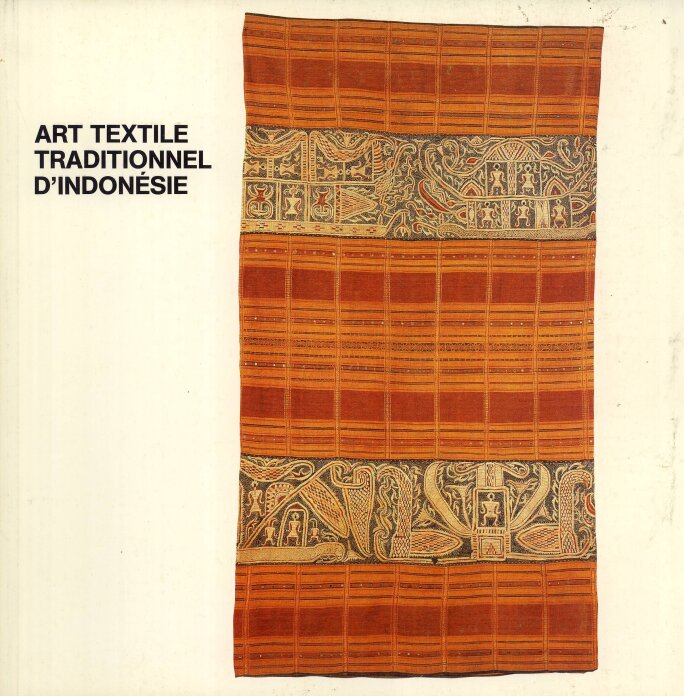

S otheby's La Trame du Rêve is the first major collection of antique Indonesian textiles to come up for sale at international auction. It reflects the increasing importance of textiles on the marketplace and at world institutions. Not long ago, textiles were still often overlooked at most large museums and galleries.

Today, the collections of the Met, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Victoria and Albert, the National Gallery of Australia, the Musée du Quai Branly, the Washington Textile Museum and the National Gallery of Indonesia expand fast and many large dedicated textiles exhibitions with lavish catalogues are curated every year. Among these, Indonesian textiles are prominent thanks to their wealth of styles, their exceptional beauty and their huge historical and ethnographic importance.

This private collection presents an exceptional array of rare pieces spanning the entire Indonesian Archipelago.

As Robyn Maxwell, senior Curator of Asian Arts at the Australian National Gallery summarized it in the title of her exhibition and book, the foundation of arts and weaving in Indonesian societies rests on three pillars: “Life, Death & Magic”. Beyond their intended decorative power, each piece in this sale was created with a societal purpose in mind – “a rite of passage” and the need to respect the “Adat”, the customary law of the indigenous peoples of Indonesia and an unwritten code governing all aspects of personal conduct and of life’s major events from birth to death: weddings, funerals, the coming of age or various religious functions.

Adat forms find their origin in the ancient animist past of these islands. They markedly evolved with the Hindu and Buddhist religious and cultural influence which reached Indonesia as early as the 2nd century CE and later with the Islamic and European legal systems merging with the old indigenous lore.

In addition to the Adat, early textiles imports from India, China and later Portugal and Holland, deeply influenced the designs and symbols of Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Sumba, Flores and Timor, as evidenced in almost every textile in this collection.

The scarcity of the pieces in this sale is enhanced by most having been created as the exclusive appanage of higher social groups – kings, princes, nobles, priests, village chieftains, shamans – which both conferred them status and value and limited the numbers produced. They were kept as heirlooms, sometimes for hundreds of years, passed from a generation to the next and continuously displayed at important life events, even when the weaving techniques had been lost among a particular group.

This sale offers collectors a unique opportunity to add highly coveted examples, collected decades ago and for some of them, exhibited as early as 1983, by Georges Breguet, one of the World’s best experts and collectors of Indonesian textiles, at the Musée de L’Elysée in Lausanne.

Among the most important lots, the sale offers six exceptional museum-quality “Palepai” ship-cloths. These were ceremonial wall-hangings of the Paminggir and Pasisir people of South-Sumatra and have not been woven in over a century, except for lower quality copies made after the 1970s for the tourist trade.

But lot 5, together with lot 49, belong to the rarest type known, with a double ship motif. Fewer that ten such pieces are known.

A lot in the Palepai’s iconography has been lost. Late field research, long after these textiles had stopped being produced or used, didn’t bring convincing data. But we know these ritual textiles were prestige pieces, strictly woven for the Paminggir noble class and hung behind them at important life transition ceremonies such as weddings, reaching adulthood and chiefdom displays of status or death, and were kept as heirlooms. Their refined iconography speaks of times predating the conversion of Sumatran people to Hinduism, Buddhism or later to Islam. Probably connected to their creation myth, human and mythical animal figures populated these ships ( See the rich ornamentation of Lot 21), as they do on their cousin pieces also present in this sale, the Tatibin and Tampan and on some rare “Tapis” skirts.

(For similar double ship examples, see: Textiles of Southeast Asia-National gallery of Australia, p.113 / Early Indonesian textiles, the metropolitan Museum of Art (p.93 for an unique embroidered Palepai) / Life, Death and Magic, p.17)

Lot 16, a long Lawo Butu ceremonial skirt of the Ngada people of Flores Island, is fascinating, not just because of its scarcity but because of its extraordinary composition, mixing sophisticated predominantly indigo ikat weave with old trade beads forming mysterious designs (human figures, rhombs, horses, chickens…) whose significance (fertility, auguring the state of future crops?) is mostly lost.

Still, we know from late field research and rare photographs that they were highly important ceremonial skirts, probably worn by mature women of the highest social rank.

So rare it is and such a highly complex weave that lot 16 could easily be described as the Holy Grail of many a collector of Indonesian textiles.

(For similar examples: Textiles of South-East Asia, National Gallery of Australia, p.141 / Woven messages “Indonesian Textile Tradition in Course of time, p.182 /Thread and Fire, the Francisco Capelo collection by Linda.S.McIntosh,p.92)

Finally, the two magnificent Kain Panjang batik hip wrappers in this lot, would elevate any Indonesian batik collection. Their complex patterning makes them masterpieces of the genre. The white backgound batif was created in Indramayu on the North-Coast of Java for the affluent Peranakan Chinese merchant class who adopted some of the Javanese clothing traditions to differentiate themselves form the lower status new Chinese immigrants at the end of the 19th century.

The second one with a deep blue field and its deep red and white ends, was created in Semarang, on the North-coast of Java in the last quarter of the 19th century. Semarang batiks draw their design and inspiration from Lasem batik. Typically, such high-end creations would have been ordered by rich Peranakan Chinese families or members of the Javanese elite.

The Indramayu batik, with its rich drawing of birds of paradise, flowers and the presence of remnants of gold leaf mourning cloths, informs us that it was likely donned by a bride-to -be, just before her wedding. Both are in very fine and incredibly soft cotton.

(For similar examples: Thread and Fire, the Francisco Capelo collection by Linda.S.McIntosh,p.148 /5 centuries of Indonesian Textiles, p.166-167)