“The quality that we call beauty, however, must always grow from the realities of life, and our ancestors, forced to live in dark rooms, presently came to discover beauty in shadows, ultimately to guide shadows towards beauty’s ends.”

T

he 1933 essay “In Praise of Shadows” by literary great Jun’ichirō Tanizaki draws us into other realms – of earlier times when we used to inhabit dark interiors, where light and shadow interplay and treasured works of art remain half hidden in deeply recessed alcoves. In these rooms, delicate light steals in so softly from the shadows that it offers the beholder but a precious glimpse of the surrounding beauty.

“Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty,” Tanizaki’s meditation on aesthetics bespeaks a beauty that emerges out of repose, not of exertion, and within that stillness, the deep shadows against light shadows move from concealment to revelation.

The relationship of shadow and light is distinct from chiaroscuro which relies on the high contrast between highlights and deep shadows. Tanizaki shies away from the intense shine of what he called a “shallow brilliance,” instead embracing the “pensive luster” of an artifact. Take for example, an extremely rare votive figure of Maitreya from the Northern Wei dynasty. Over centuries, this magnificent bronze statue bears a so-called “sheen of antiquity.”

This sheen is, oddly enough, “the glow of grime.” When gazing upon the details of the bronze Maitreya, it appears to emit a subtle light and the centuries of darkening have enhanced its sensitive modelling, which was inspired by Gandharan art. Among the largest of all Northern Wei bronze Buddhist sculptures recorded in private hands, this figure encapsulates the finest qualities of sculpture of the dynasty. It is reserved in near pristine condition, with a dated dedicatory inscription on the reverse stating the name of the patron and his commemoration of his deceased parents.

“The words denoting this glow describe a polish that comes of being touched over and over again, a sheen produced by the oils that naturally permeate an object over years of handling – which is to say grime. Yet for better or for worse we do love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colors and the sheen that call to mind the past that made them. Living in these old houses amongst these old objects is in some mysterious way a source of peace and repose.”

“...a depth and richness like that of a still, dark pond, a beauty I had not before seen.”

We first notice the darkness of Jian tea bowls with their rich black glaze, and moving deeper into the shadows, we find the interspersed patterns of lightness and darkness, metallic silvery to coppery streaks emanating an otherworldly spectral sheen. The immersion brings to mind Tanizaki’s enraptured description of a bowl, comparing its beauty to a still, dark pond. The ravishing glaze effects of this exceptional and rare heirloom rank it among the rarest and most highly coveted of all nogime temmoku tea bowls. From the Aoyama Studio Collection, the current example is endowed with an illustrious provenance, including the collection of Roger Pilkington (1928-1969).

“We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.”

The superb and liberal russet splashes appear in a pattern evoking the mottles of partridge feathers. The glaze gives truth to the notion that beauty would not exist without shadow, as the rich russet mottling is shown to advantage against the deep black-glazed interior. This exceptionally rare example, also from the Aoyama Studio Collection, was formerly in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Yeung Wing Tak and dealt through Eskenazi twice.

“The Chinese also love jade. That strange lump of stone with its faintly muddy light, like the crystallized air of the centuries, melting dimly, dully back, deeper and deeper […] we seem to find in its cloudiness the accumulation of the long Chinese past, we think how appropriate it is that the Chinese should admire that surface and that shadow.”

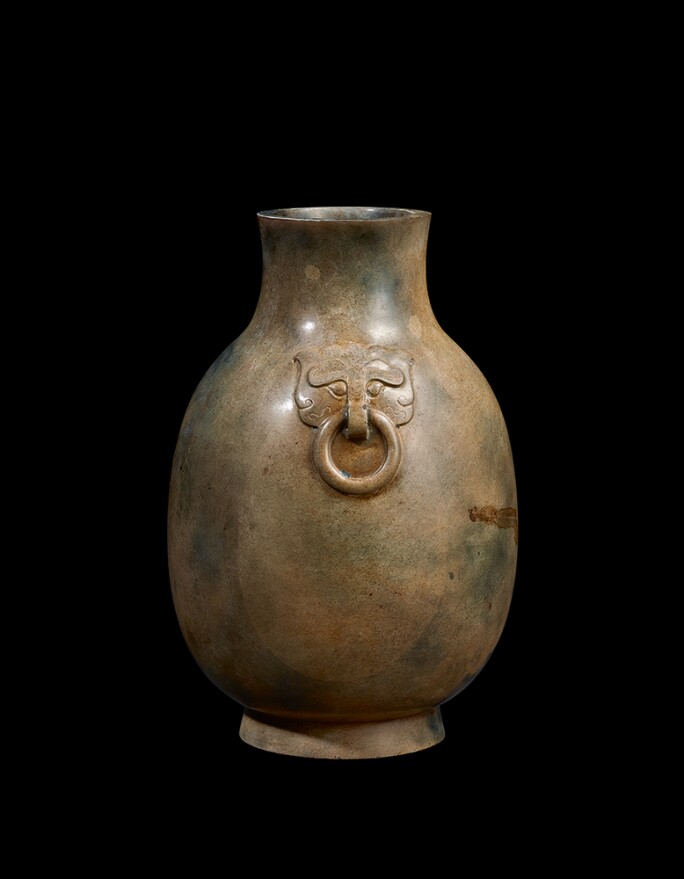

This Eastern Han dynasty jade vase with animal masks possesses a rare form with an attractive mottled patina. It is well known that this precious and durable stone has been revered in China for its unmatched translucency, like clouds suspended within the stone that softens the light into a muted glow. In a most poetic fashion, Tanizaki sees jade the “crystallized air of centuries,” and indeed in the present example, the patina points to the luster of millennia past. This jade vase comes from the renowned Hei-Chi collection and is preserved in very good condition.

“We do prefer a pensive luster to a shadow brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artefact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity.”

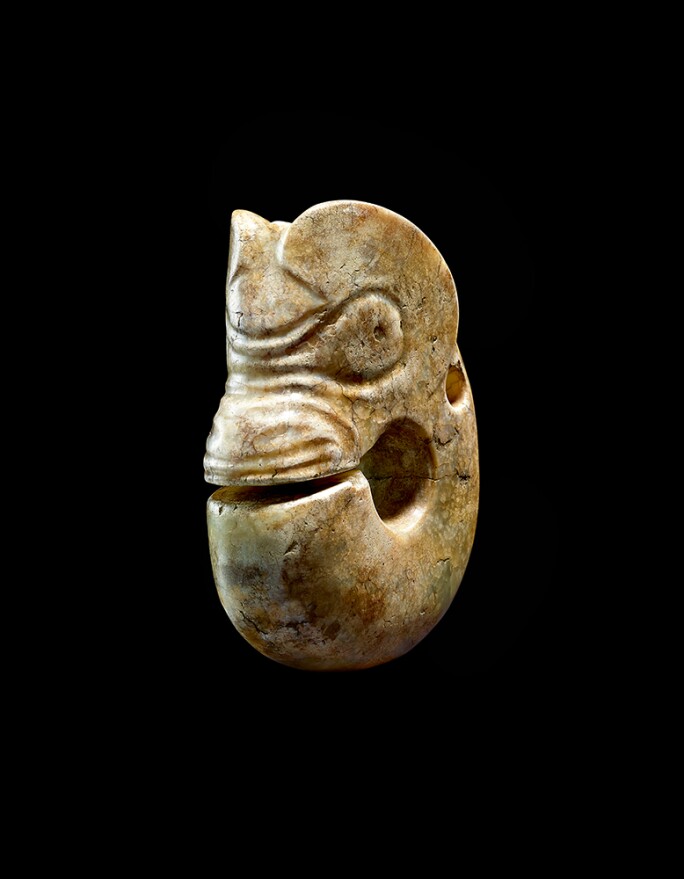

The enigmatic Hongshan culture, which flourished at the very dawn of civilization, left a legacy of one of the most significant Neolithic jade cultures in China. This rare yellow jade zhulong “pig dragon” is considered the precursor for the ornamentation of Chinese mythical dragons in later symbolic art. Imagine unearthing such a stone, a rare object which glows with a shadowy light, that must have been created for ritual purposes and yet remains shrouded in mystery. This piece, from the renowned Hei-Chi collection, is a very large example of its type.

“The lacquerware of the past was finished in black, brown, or red, colors built up of countless layers of darkness, the inevitable product of the darkness in which life was lived.”

This superbly carved cinnabar lacquer magpie tray from the Yuan dynasty, comes from the Kaisendo Museum, and makes up part of a group we are offering this season. The round shape and the finely carved magpie design demonstrate the skilled craftsmanship of the lacquer tray which remains preserved in very good condition. Tanizaki speaks of the lacquer as a thing carved from the shadows: “The sheen of the lacquer, set out in the night, reflects the wavering candlelight, announcing the drafts that find their way from time to time into the quiet room, luring one into a state of reverie. If the lacquer is taken away, much of the spell disappears from the dream world.”

Source

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, In Praise of Shadows (first ed., 1933, Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker, trans., New Haven, 1977)