T he New York session of Sculpture: Africa, Pacific, Americas celebrates the great civilizations of sub-Saharan Africa, the dreamlike worlds of the Pacific Islands, the transformative imagery of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and the spiritual presence of the first cultures of North America. Fresh-to-the-market material is selected from private collections and estates throughout the United States. Many works have been extensively published and exhibited, and bear iconic provenances including western collectors such as Paul Guillaume, Helena Rubinstein, and Sir John Richardson.

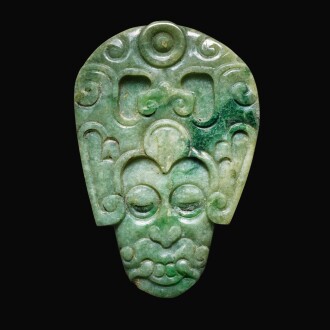

Objects of power in the Olmec Preclassic era (900-100 BC) were created in human and mythological form, using stones considered inherently connected to nature’s life force. Deity images were developed from composite figures of land, sea and sky, creating an omnipotent magical creature, such as the Olmec greenstone ‘dragon’ amulet. The mournful and evocative Olmec head represents a core tenant of the Olmec symbolic canon- the meditative power of the basic human figure. The tall Olmec standing figure from the later Preclassic period, epitomizes strength in his overt musculature and commanding aura. These tenants of Olmec art and symbolism were the basis for many of the later Maya artistic validations of power. The Maya jade pendant of a deity with the soaring effigy headdress, was an elite costume ornament of jewel-like quality and masterful carving.

Legendary British Art Historian Sir John Richardson kept company with extraordinary people and extraordinary objects. In the 1950s he befriended Fernand Léger, Nicolas de Staël, and Pablo Picasso, and would devote much of his long life to Picasso’s biography. The two sculptures offered here sat atop Richardson’s desk in the studio of his Fifth Avenue apartment in New York: a stunningly cubistic Mezcala Statuette from West Mexico, and an ancient and ferocious We Mask from present day Côte d'Ivoire. The mask had first been exhibited in New York by the avant garde Mexican artist Marius de Zayas in 1918, in collaboration with Paul Guillaume, who later sold it to the British sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest collector of African Art. Richardson acquired it at the auction of Epstein’s estate in 1961.

View Lot

Bristling with spiritual power, secretive objects were used across the West African region of the Sahel and belonged to associations that governed every individual’s mogoya, or personhood, and served as powerful mediators between individuals, the natural world, and the supernatural spirit worlds. Composed of a multitude of organic plant and animal materials, these elaborate figures are both representational and abstract, inspiring fear and respect among those who encounter them. Kòmòkun Masks, which can only be viewed by initiates, were worn during ceremonies of the Kòmò power association, a group that is responsible for judicial decisions. Similarly, Boliw (plural of Boli) were handled by a select group of older men who hold judicial and political authority in most Bamana villages. When resolving legal cases, the elders consult the Boli who divines the culprit and delivers a sentence. Lastly, Senufo Oracle Figures were used in rituals called Kafigeledjo, a Senufo term that can be roughly translated as "he who speaks the truth." Their truth-telling function helps to maintain social order by uncovering false testimony and reestablishing equilibrium in the community.

This animated, eclectic collection of ceramic figures from the Estate of Patsy R. Taylor, underscores the playful, deeply human side of ancient West Mexican art. Collected by Gray and Patsy Taylor in the early 1970’s, these sculptures have a lifelike, individualized quality, which transports them into the present. The ancient artists created these naturalistic and stylized figures with elaborate ornaments, which commemorate ancient communal ceremonies and honor the deceased in order to ensure the vital ‘inheritance of power’ among important clans of the village communities.

A Personal Reflection

The Taylor Collection of Ancient West Mexican Sculpture

‘My parents’ passion for West Mexican ceramics stemmed from aesthetic influences on my architect father, Gray Taylor, and the interest in contemporary art he shared with his wife, Patsy. In 1951, he built a house that reflected the contemporary architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. The interior was replete with Danish modern pieces, many of them by notable master craftsman Hans Wegman. In later years, they also acquired contemporary art by Louise Nevelson, Wendell Castle and Paul Evans, among others.

Several trips to Mexico during the early 1960s introduced my parents to Pre-Columbian art. They were taken by West Mexican ceramics, in which they saw bold sculptural forms with plastic modeling and appealing anecdotal qualities. The anatomical distortions resonated with the Abstract Expressionist movement and thus, appealed to collectors of contemporary art. They began to purchase these ancient ceramics from dealers in New York City.

A highlight of this collection is the seated joined Jalisco couple, with the man holding a cup and the woman a plate. This was my father’s favorite piece and he always said of this loving couple, “He’s got the cup of tequila and she’s got the bowl of chips.”’

-Dicey Taylor, Ph.D.