In the 1970s and 80s, my Moscow circle of artists included mostly conceptual and Sots-artists [Art based on the clichés of socialist realism, predominantly ironic and mocking the Soviet sacred cows]. They came from various groups like Collective Actions, Sretensky Boulevard (also known as the Kabakov group), Nest, Toadstool, and others – it was a close association of artists of visually different trends, united by their interest in contemporary Western art and philosophy. Another faction of older nonconformists stemming from or close to the Lianozovo group was outside of that circle but well-known to everyone. I got closer to them in the eighties.

Anyway, our community embraced about fifty artists, poets and writers, who shared a common view on art and society. We socialised every other day on any significant pretext. In those years, the desperate situation of being outcasts behind the burlap curtain and the small numbers of participants of the semi-official and underground exhibitions promised a truly friendly relationship between the artists, and inherent value of each member of the community, as well as of each work.

In the 1970s the subject of potential emigration hung over the Soviet intelligentsia and indeed resulted in the departure of a significant number of artists, not to mention writers, actors, translators, etc., to the West. Those who lacked the will or confidence remained in Russia, but by the beginning of the 1980s they suddenly felt like being left ‘behind a closed gate in a deserted courtyard’. Many creative people fell into a relentless depression because of the insoluble psychological contradictions (to leave or not to leave? – that was the question!): they could no longer see any prospects for improvement of the situation with unofficial art, or, in a broader sense, with free creativity in their own country. The remaining semi-dissident, semi-official artists began to fear that they would eventually just disappear from the face of the Earth and the territory of art without any objective traces left behind them due to the total lack of opportunities to show their work.

This fear, hardly comprehensible in the 21st century, forced many artists of the post-conceptual circle to close ranks in the most literal sense. They began to document their activities with the help of limited home publications (samizdat), intended primarily for in-house use.

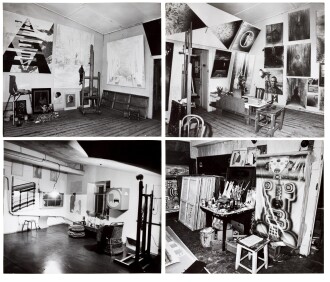

The artists started to write essays for a narrow circle of like-minded people, collect other artists' work and, when possible, send those collections and materials to the West, where, as the artists saw it from Moscow, there were at least some opportunities for publication or public exposure. Thus in 1981, the latest works of our community members were published in the first issue of the Moscow Archive of New Arts (MANI). In the next couple of years, I took an active part in this project as a photographer, co-editor and co-production manager. I endlessly visited artists' studios, collecting materials and photographing their works for the Archive, because there were not so many photographers in our midst. Besides, the artists trusted me more than anyone else as I was engaged in similar activities.

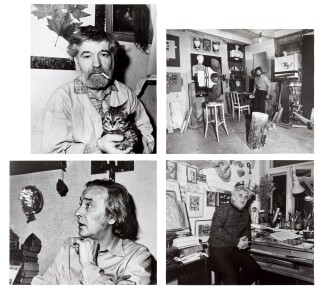

Eventually, I began to want to elucidate in more detail—to museumify [ie. convert into a museum.]—the infrastructure of our busy creative life of the time. Thus several artist’s albums appeared that featured conceptual photographic series with accompanying texts. Among them are the albums, In the Studios produced in collaboration with the artist Vadim Zakharov, in two volumes (1982-85), Artists’ Rooms (1985), a series of conceptual portraits of artists and writers entitled Love Me, Love My Umbrella (1984), and some other projects.

As hinted above, In the Studios arose from working on MANI. I adored, as a rule, certain details in the studios that no one else paid any attention to. Somehow it occurred to me that very interesting material was left unnoticed. I had always believed that you could only appreciate a painting by hanging out with the artists and seeing how they worked, by empathizing with the atmosphere in the studio. So there I used photography both as a means of artistic expression and as a means of documentation.

Love me, Love my Umbrella came a bit later when I decided that I should make conceptual portraits of the artists. I'd just read James Joyce’s story, Giacomo Joyce, and I liked the concluding phrase which served as a title, as a unifying idea for a shoot with some everyday object. I decided to photograph everyone with umbrellas that became a hidden symbol for art.

The Artists’ Rooms project was also based on the concept of documenting the artist's home universe, with his or her bed being its centre.