S otheby's is honored to present furniture, fine art and decorative objects from the personal collection of legendary interior designer Mario Buatta in a dedicated two-day auction. The sale includes a panoply of nearly 1,000 works that Buatta lived with in his Upper East Side apartment in New York City as well as the William Mason House – an historic gothic-style home in Thompson, Connecticut – and feature many pieces that have long been admired in showhouse rooms and shelter magazines over the years. Here, discover the vast array of styles beloved by Buatta.

Regency

P olitically, the Regency is defined as the period between 1811 and 1820 when Parliament named the Prince of Wales as Regent to his physically and mentally incapacitated father George III. In the decorative arts, the term refers to a period spanning the late 1790s to the end of George IV’s reign in 1830 or even that of William IV in 1837, which marked a definitive break from 18th-century Georgian taste. The Regency style had many influences both internally and from abroad, beginning with the neoclassicism of the late Louis XVI period practiced by the Prince of Wales’ architect Henry Holland followed by the more archaeologically-inspired French Empire style developed by Napoleon’s tastemakers Percier and Fontaine, based on Greek and Roman antiquity and paralleled in England by the work of the architect Charles Heathcote Tatham and the connoisseur-collector Thomas Hope. Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign documented by the artist and archaeologist Vivant Denon sparked an interest in Egyptian motifs, and the exotic appeal of Chinese and Gothic ornament continued to play a role. One decorative element that proved particularly popular was the dolphin, derived from ancient Roman art and frequently seen in France due to its associations with the heir to the throne the dauphin, and also previously favoured by William Kent in his furniture designs. As a maritime symbol, dolphins would take on a new resonance after Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in 1805 asurred Britain’s status as the world’s dominant naval power. The Regency Style came to be regarded as the pinnacle of classical elegance and enjoyed a revival in the 20th century on both sides of the Atlantic among designers ranging from Sibyl Colefax and Syrie Maugham to Dorothy Draper, Elsie de Wolfe and Billy Haines.

Explore Regency

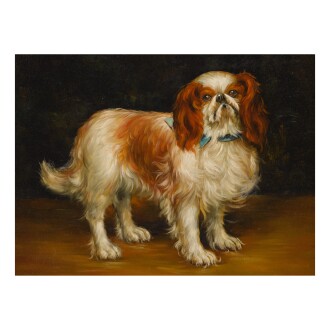

Dog Painting

F rom “Cave Canem”, the mosaic at the entrance to the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii created in the 1st Century AD, to Pieter Breughel’s frosty Hunters in the Snow with their large pack of hunting dogs, to Thomas Gainsborough’s frothy portraits of British aristocracy and their dogs, man’s best friend has appeared again and again throughout the history of art. In England, Europe, Asia and eventually America, the dog’s role as a protector, working herder or retriever, pet, loyal companion and symbol of unconditional love was celebrated and immortalized through their inclusion in works of art, both painted and sculpted. By the 19th Century, inspired by Queen Victoria’s love of animals - and her patronage of animal artists such as John Frederick Herring Snr. And Sir Edwin Landseer - Victorian collectors went mad for dog portraiture. Buatta’s collection of dog paintings – and especially Cavalier King Charles Spaniels – carried on the proud tradition of charming and comical depictions of dogs while introducing clients and collectors alike to the charms of dogs in art.

Explore Dog Painting

Japanning

F ollowing the establishment of trading links with Asia by Portuguese explorers in the early 1500s, works of art from the Far East began arriving the West in greater quantities by the early 17th century with the foundation of the East India trading companies, in England (1600), Holland (1602), Denmark (1616) and France (1664). In addition to much sought-after porcelain, Europeans were introduced to chests, cabinets, screens and small wooden objects decorated in lacquer, a brilliant and durable surface obtained by painstakingly building up multiple layers of sap from the indigenous lacquer tree rhus vernicifera. Such exotic but functional objects were highly desirable but also expensive, encouraging European artisans to seek a method of imitating Asian lacquer. This was first done in Italy using gum varnish from the sandarac tree native to North Africa, and the technique soon spread to France, the Low Countries, Germany and England, where it was called ‘japanning’, as lacquer wares from Japan were regarded as superior to Chinese production. The design inspiration for japanned work however was resolutely Chinese, using engravings of Chinese figures, architecture and ornament that appeared in various publications such as the Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof’s Embassy from the East-India Company (1665, translated into English in 1673) and were compiled in a single volume A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing by John Stalker and George Parker (1688) that became a bible for professional and amateur lacquer artists.

The William and Mary, Queen Anne and early Georgian periods were a golden age of English japanning, which unlike Japanese lacquer employed numerous different colored grounds in addition to black, with red being extremely popular and used on clock cases, chairs, and especially bureau cabinets, a specialty of the prolific London workshop of Giles Grendey (1693-1780). The popularity of japanning waned somewhat in the second half of the 18th century but came back into fashion during the Regency and Victorian eras, when the technique was extended to new surfaces such as papier-mâché and tinware.

Explore Japanning

English Enamels

E nglish enamels are among the most charming productions of the Georgian rococo. First created in Battersea, that name has stuck with the art form – even though production soon moved elsewhere, particularly to South Staffordshire. As collectibles, they were rediscovered in the early 20th century, with Nellie Ionides and Queen Mary building notable groups. This, in turn, inspired American collectors including Jackie Kennedy, Betsey Whitney, Brooke Astor and Bunny Mellon, who appreciated the delicate aspect of the candlesticks, snuff boxes, and novelty-form bonbonnières and nutmeg graters.

Explore English Enamels

Chinese Export

T rading links between Europe and Asia began were established by the Portuguese in the early 16th century and greatly expanded a century later with the formal establishment of East India trading companies by most of the leading European powers. Although the primary focus was on commodities such as tea, spices, and textiles, merchant ships also began exporting Chinese porcelain, often used as ballast stocked in the lowest level of the ship as it was impervious to water damage. As the secret to manufacturing true porcelain was still unknown in Europe, such objects created a sensation and were avidly sought after. In response, Chinese ceramic workshops began producing work specifically for export to the West, particularly blue and white wares, which became known as kraak porcelain from the Dutch word for carracks, or Portuguese trading vessels. Between 1602 and 1685 the Dutch East India Company imported between 30 and 35 million objects of Chinese and Japanese export porcelain into Europe, and demand for export porcelain remained high well into the 18th century.

By the 1750s European traders were officially restricted to the port of Canton (Guangzhou), where their authorized presence was limited to a waterfront factory district run by a monopoly of Chinese merchants known as the Hong. The range of goods traded expanded to paintings and watercolors, silver, carved ivories, enamels, fans, and increasingly furniture, both in Chinese hardwoods and lacquer. Japanese lacquer had long been regarded by Europeans as superior to Chinese, but because the Japanese emperors restricted all European trade to Dutch ships until the mid-19th century, Chinese merchants sought to undercut their market by producing furniture and objects in Japanese-inspired gold and black lacquer destined for export through all the East Indian companies. Forms were often based specifically on European models, using drawings, pattern books, models, and potentially actual prototypes sent from the West. As one Swedish trader observed in 1751, "the joiners here copy everything that is shown to them." Furniture production continued well into the 1800s and was also marketed to domestic clients or Europeans resident in other trading centers in Southeast Asia and India.