F ew artists have been as influential with a singular gesture as Lucio Fontana slashing his canvases for the Tagli (Cut) series. The first major survey of the Argentine-Italian artist, currently on show at the Met Breuer and The Met Fifth Avenue, New York, seeks to demonstrate Fontana’s cultural worth and influence beyond his famous slashed canvases. It positions him as innovator and the first European artist to successfully promote the concept of making art as a performance. Fontana’s artistic career began as a sculptor before he moved on to painting and finally his pioneering light installations. Here are some facts everyone should know about him.

1. He fought in the First World War

Born in Rosario de Santa Fe, Argentina, in 1899, to Italian parents, Fontana moved to Italy in 1905 to go to school. Like many of the Italian Futurists, whose work and outlook he greatly admired, he volunteered for the Italian army during the First World War, from 1916 to 1918, reaching the rank of second lieutenant in the infantry. He was discharged with a silver campaign medal, having been wounded in the arm. Though he was initially attracted to the “action squadrons” of the nascent fascist movement in Italy, his experience of war made him wary of becoming further invested in the simmering political tensions at the time.

2. Fontana didn’t begin creating canvas-based art until he was in his 50s

Escaping the political turmoil of Europe, Fontana moved back to Argentina in 1921 and began making busts for his father’s workshop, which specialised in making sculptures for graveyards. As early as 1925, was gaining critical acclaim for his sculptures featuring abstract human forms and unusual materials, such as Homo nero, 1930, which he layered with tar. He made many sculptural and architectural works for the fascist regime in Italy, including a now-lost bust of Benito Mussolini himself, a connection that marred his reputation for decades.

3. He worked as a teacher for much of his life

Throughout his life Fontana taught at traditional art schools in Argentina, including Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes “Manuel Belgrano” in Buenos Aires. In 1946 he co-founded the experimental Altamira School of Arts in Buenos Aires. As the professor of sculpting, he helped to promote the school’s philosophy that in light of recent scientific discoveries, a new art was necessary to reflect the modern world. He encouraged his students to embrace new conceptual approaches to creating art, urging them to forsake painting to make innovative art, for example projecting light.

4. He helped publish a manifesto envisioning a new art

Under the direction of Fontana, in 1946 the artists and students of Altamira School of Arts published the Manifesto Blanco (The White Manifesto), a pamphlet setting out the goals for the creation of a “spatialist” art. It called for this art to engage with the technology of the day to achieve a radical new format that melded architecture, sculpture and painting, as well as embrace the subconscious. The ideas put forward in the manifesto influenced much of Fontana’s mature work.

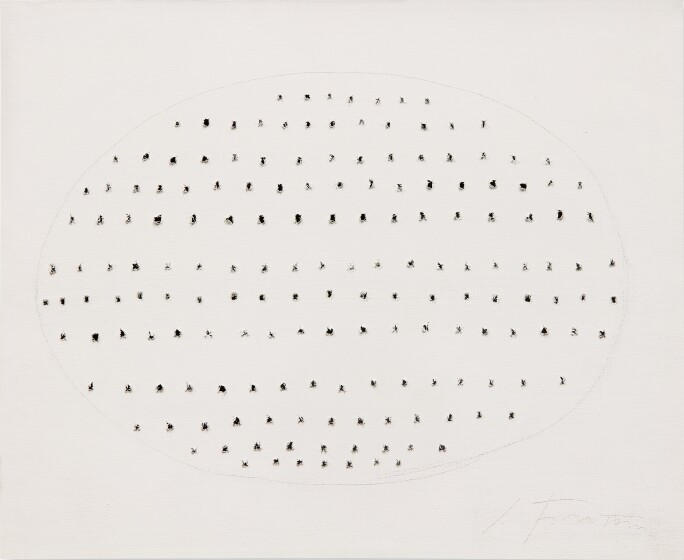

5. Fontana was fascinated by space

The artist was obsessed by the concept of space and space travel. He founded the Spatialism art movement in 1947, not long after the first ever photos of Earth taken from a rocket appeared in magazines around the world. He began puncturing canvases and works on paper with his I Buchi - Holes series, 1949–68. “It’s not true that I made holes in the canvas in order to destroy it, no, I made holes in order to discover, to find the cosmos of an unknown dimension,” he once said. The artist continued this quest with works such as Ambiente Spaziale, 1949 – a pioneering example of art installation comprising an abstract object painted with phosphorescent paint and lit by a neon light, and La fine di Dio, 1963–64, a series of punctured egg-shaped canvases, which he explained signified “the infinite, something inconceivable, the end of figurative representation, the beginning of nothing”.

6. He was friends with Yves Klein

In 1957, the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan held an exhibition of Yves Klein’s Blue Monochromes, a series of almost identical blue paintings. “Just two buyers turned up so far, a well-known tailor who is also a collector of abstract art, and painter and sculptor Lucio Fontana, the one who pierces holes,” reported journalist and writer Dino Buzzati. Having bought one of the Blue Monochromes, Fontana and Klein became friends, visiting each other in Milan and Paris. Although from different generations, both artists found resonance in the other’s work. In a literal sense their work drew upon similar references, such as Medieval paintings, but more significantly they were united in their desire to go “beyond” the work, expanding the concept of a painting beyond its frame or surface, redefining the very idea of an artwork itself.

7. His work is in over 100 museums

Fontana’s works can be found in the permanent collections of more than 100 museums, including Tate Modern in London, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The largest collection is owned by the Casamonti Family, whose heir Roberto Casamonti founded Tornabuoni Art in 1981. The gallery, which specialises in Italian art from the second half of the 20th century, has outposts in cities such as Florence, London, Milan and Paris.

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 23 January-14 April