H e then took what might seem to be a self-defeating decision after the Biennale: he immediately asked his studio assistant back in New York to destroy the silkscreens he had used in making his award-winning paintings, seeking to avoid any temptation to repeat himself or to cash in on his win. This radical step indicated an artist who constantly changed direction, taking on new formats just when he seemed to be finding his way in any particular vein.

Rauschenberg went on to forge a career that spanned just about every conceivable medium, and which included collaborations with composers, writers, scientists, theatre directors and choreographers. His creations, ranging from painting and collage to assemblage and performance, engage in the idioms of Cubism, Dada, Pop and conceptual art, to name but a few.

Emerging on to the American scene while the gestural painting of the Abstract Expressionists was still setting the terms, Rauschenberg, along with peers including fellow artist Jasper Johns and older contemporaries such as John Cage, smashed the mould of art-making, just as he discarded the silkscreens behind his Venice victory.

“Rauschenberg’s mode of working and being in the world introduced a kind of 21st-century thinking, even in the 20th century,” says Leah Dickerman, the director of editorial and content strategy at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

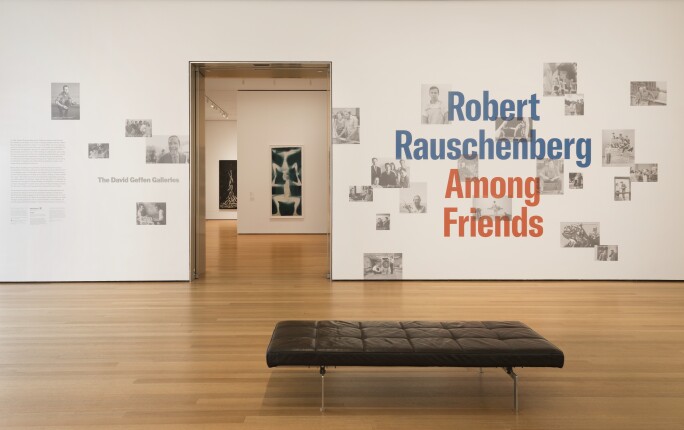

Dickerman organised the past exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends with Achim Borchardt-Hume, the director of exhibitions at Tate Modern, London.

Among the key concepts Rauschenberg pioneered was what a writer for Art in America went so far as to call his “disregard for authorship”, by handing over the controls to other artists and to chance.

One way in which to measure Rauschenberg’s impact is his deep influence on other giants of the mid-century cultural sphere. Early on, he and Johns had studios in the same building; they would frequently visit each other and exchange ideas, making them something like an American Picasso and Braque. Cage, for his part, was emboldened by Rauschenberg to create perhaps his best-known composition, 4’33”, in which a pianist sits in silence for the titular amount of time, allowing the noises in the auditorium to create the sound of the piece. For this work, Cage drew inspiration from Rauschenberg’s White Paintings, which incorporated phenomena of the rooms in which they were shown, even the shadows cast on the canvases by viewers.

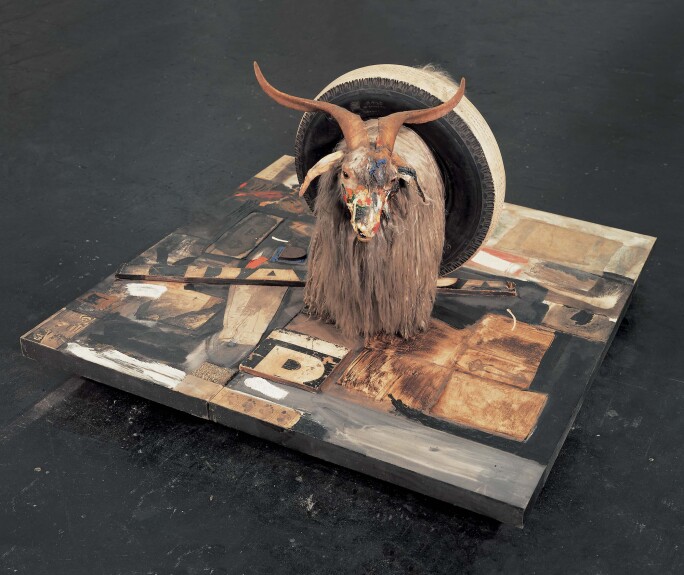

If these works mark out one pole of Rauschenberg’s production, a kind of Minimalism avant la lettre, then works such as his Combines represent the opposite aesthetic pole. These introduced a riot of everyday images and objects, such as newspaper clippings, bedsheets and even a taxidermied angora goat, into assemblages that illustrated his trademark goal: “To operate in the gap between art and life.”

Ten years after his death, in Captiva, Florida, in May 2008, Rauschenberg continues to exert an influence on younger artists that is impossible to overstate. “There are probably more artists than not who are indebted to Rauschenberg,” says David White, the senior curator at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

“When you walk into a gallery and the art is made of the stuff of the world, or has a performative element, or embraces technology, or the work comes off the wall,” Dickerman says, “that’s all made possible by Rauschenberg.”

Banner: Robert Rauschenberg, The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece, 1981–1998, © 2016 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation