Property from the Collection of J. Robert Maguire

The Bill of Rights | Amending the United States Constitution: “further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added”

Auction Closed

June 26, 04:10 PM GMT

Estimate

1,000,000 - 2,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

The Bill of Rights

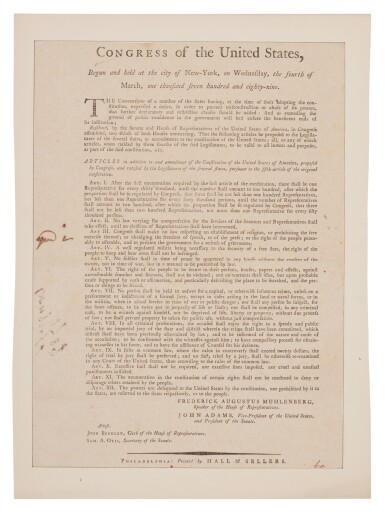

Congress of the United States, Begun and held at the city of New-York, on Wednesday the fourth of March, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-nine.

The Conventions of a number of the States having, at the time of their adopting the constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the government will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution;

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, two thirds of both Houses concurring, That the following articles be proposed to the Legislatures of the several states, as amendments to the constitution of the United States; all, or any of which, when ratified by three fourths of the said Legislatures, to be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of the said constitution, viz.

Articles in addition to and amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America, proposed by Congress, and ratified by the Legislatures of the several states, pursuant to the fifth article of the original constitution. … Art. III. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. … Art. XII. The powers not delegated to the United States by the constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people. Philadelphia: Printed by Hall & Sellers, [10–12 November 1789]

Letterpress handbill, or small broadside (266 x 194 mm) on a half-sheet of laid paper, numbered in manuscript “60” lower left, annotated “agreed to”(?) in left margin opposite the third proposed amendment, endorsed on verso “Congress 1789”; inlaid and rebacked, the rebacking closing a separation at central horizontal fold just obscuring the lowest portion of six words but not affecting legibility.

An unrecorded and evidently unique handbill printing of the Bill of Rights, the first proposed amendments to the Constitution to be submitted to the states for ratification.

The present copy is apparently the sole survivor from an edition of one hundred copies ordered to be printed by the Pennsylvania General Assembly for the use of its members during their debate on ratification.

This is the earliest of only three broadside-format editions of the Bill of Rights printed during the period of debate and adoption of the amendments—and the only one intended as an official, working legislative document.

Hall and Sellers’s handbill is unrecorded by Evans, ESTC, Hildeburn, and all other standard bibliographic and reference resources.

The Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin-Madison, has no record of the Hall and Sellers separate printing of the proposed amendments to the Constitution and was previously unaware that a copy of this printing was extant. This copy is known only from its appearance in a long-forgotten Charles Heartman auction of more than a century ago and was recently rediscovered in the Collection of J. Robert Maguire.

"When the first Congress, along with President George Washington, gathered in New York City in 1789, Americans did not assume that the process of constitution-making was now—or ever would be—complete. Many expected the document to be amended almost immediately. Several state conventions had ratified the Constitution with the expectation that their suggestions for its improvement would be taken up and adopted. Most of the proposed amendments grew out of one of the main critiques that Antifederalists such as the Pennsylvania addressers had leveled against the Constitution: that it lacked a bill of rights resembling those attached to most state constitutions. Americans strongly desired guarantees that the federal government would not use its considerable powers to infringe key individual rights. … The Philadelphia convention may not have given much thought to a bill of rights, but it had provided a method by which Americans could add one. Article V of the Constitution outlined the procedure for amending the nation's fundamental law" (Hrdlicka, Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions, pp. 81–82).

There was no shortage of suggestions as to what a bill of rights should contain. In addition to the provisions of the various state declarations of rights, the ratifying conventions put forth a substantial number of proposals, ranging from South Carolina's four to New York's fifty-seven. The most influential of the proposed amendments originated in Virginia's Ratifying Convention.

On 4 May 1789, a congressman from Virginia who had attended his state’s ratifying convention, James Madison, proposed in the House of Representatives that debate begin on a series of amendments to the Constitution to serve as a bill of rights. Debate began on 8 June and was then referred to a select committee of eleven which, under the close guidance of Madison, created an initial draft that was presented to the House on 28 July. That first attempt at codifying a roster of individual rights grafted its suggested revisions directly onto the text of the Constitution itself, a confusing and ambiguous method that diluted the committee's charge: creating a clearly defined set of rights to be enshrined under the protection of the United States Constitution. On 24 August the proposals were more clearly stated and formatted as "Articles in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America … pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution."

The House's proposed seventeen amendments were "printed for the consideration of the Senate," which, through debate and reconciliation, combination and elimination, produced a roster of twelve projected amendments, which was approved by the two houses of congress on 24 and 26 September 1789. Of the seventeen proposed House amendments, the third and fourth were combined into one (the present First Amendment) and with the fifth through tenth, the thirteenth, fifteenth, and seventeenth became, with minor emendation, the Bill of Rights as adopted. Of the twelve-amendment Senate version, the ten amendments that became the Bill of Rights were the third through twelfth.

Fourteen copies of the twelve proposed amendments were ordered, 28 September 1789, to be engrossed on vellum, signed by Speaker of the House Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg and Vice President and President of the Senate John Adams, attested by clerk of the House of Representatives and the secretary of the Senate. One copy was retained by the federal government and the other thirteen were transmitted, with a circular covering letter from President George Washington, to the state executives for the consideration of their respective legislatures. Washington's letter, 2 October 1789, stated simply: "In pursuance of the enclosed resolution I have the honor to transmit to your Excellency a copy of the amendments proposed to be added to the Constitution of the United States. I have the honor to be, with due consideration, Your Excellency’s most obedient Servant" (Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Twohig, 4:125).

"The ratification process usually began when the governors submitted messages to their legislatures accompanied by the public documents recently received. … The legislatures often debated the amendments in committees of the whole in which restrictive parliamentary rules were abandoned. Bills adopting some or all of the amendments were drafted and messages between legislative houses were exchanged before agreement was achieved. The bicameral legislatures of Connecticut and Massachusetts, in fact, could not agree on passing the same amendments, consequently neither side submitted certified exemplifications of the amendments that both houses had adopted.

"New Jersey became the first state to adopt the amendments on 20 November 1789. Two weeks later, Georgia’s legislature rejected the amendments as premature. … Maryland and North Carolina ratified in December 1789—the latter only a month after its ratifying convention had adopted the Constitution. Three more states (South Carolina, New Hampshire, and Delaware) ratified the amendments in January 1790. Another three states (New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) ratified by June 1790. With the 1791 ratifications by Vermont and Virginia in November and December, respectively, the necessary three-quarters of the states adopted the amendments" (Bill of Rights 1:465–66).

The twelve proposed amendments were widely circulated in newspapers, but there were evidently only three broadside editions: one printed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by Jerry Osborne Jr., 1790, known in a single example (not recorded in Evans or ESTC); another printed in Providence by Bennett Wheeler, ca. 16–18 October 1789 in an edition of one hundred and fifty copies for distribution to the town clerks of the state (Evans 22202; ESTC W35073, locating four copies in institutions); and the present, newly rediscovered, unrecorded and evidently unique version prepared for the Pennsylvania Assembly.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council received Washington’s letter with Congress’s amendments on 12 October. When the state Assembly achieved a quorum on 3 November, the Council sent it the proposed amendments. On 10 November 1789, as recorded in the minutes of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, “On motion of Mr. Carson, seconded by Mr. Kennedy, Resolved, That one hundred copies of the amendments proposed by Congress to the constitution of the United States, be printed for the use of the members of this House.” William Hall and William Sellers, the official printers for the Pennsylvania Assembly, printed the broadside. Hall and Sellers also printed the Pennsylvania Gazette on Wednesdays in Philadelphia. Strongly supporting the Constitution during the ratification debate, the Gazette was the most widely reprinted newspaper in America.

The elegant Pennsylvania printing follows very closely the layout of the fourteen copies engrossed on vellum, and the document transmitted to Pennsylvania may have served as its copy-text; the names and offices of all the signatories to the vellum copies appear here in print: Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg as Speaker of the House of Representatives and John Adams as Vice President of the United States and President of the Senate, John Beckley as clerk of the House of Representatives, and Samuel A. Otis as secretary of the Senate. But, unlike the vellum documents and the full-sheet broadsides produced by Osborne and Wheeler, the Hall and Sellers printing is on a personal scale, meant to be held and handled and read by a duly elected body of legislators debating the codification of the individual liberties that would define the nascent republic.

After considering the amendments in a committee of the whole on 27 and 30 November 1789, the Pennsylvania Assembly agreed to postpone further consideration until its next session. On 10 March 1790 the Assembly became the eighth state to adopt the amendments when it ratified the final ten of Congress’s proposals. And on 20 September 1791, the Senate and House of Representatives under the new Pennsylvania constitution of 1790 adopted Congress’s first amendment dealing with congressional apportionment.

Nationally, the first two proposed amendments failed to gain the support of three-quarters of the states, but the proposed third through twelfth amendments were adopted and became the first ten amendments to the Constitution—the Bill of Rights.

The second proposed amendment prohibited Congress from “varying the compensation for the services of the Representatives and Senators … until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.” Although this would have prevented the House and Senate from voting themselves an immediate pay raise, “Americans apparently did not consider this issue very important at the time, and the states failed to ratify the amendment. Incredibly, in 1992, after sitting on the books for over two centuries, the proposal finally achieved ratification by more than three-fourths of the (now fifty) states, and it became part of the Constitution as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment" (Hrdlicka, p. 86). The proposed first amendment, which the Pennsylvania General assembly endorsed, has yet to be ratified.

This unprepossessing little broadside goes to the very heart of the ratification of the Bill of Rights—not simply a record of what Congress proposed; not simply a commemoration of what the states adopted; but a working document: a functional, pragmatic implement in the greatest debate the nation has ever known.

PROVENANCE:

Charles F. Heartman’s Auction, No. 95 (“Rare Americana: A Fine Collection of Pamphlets, Broadsides and Books … A Collection Well Worth the Close Attention of the Discriminating Collector and Librarian”), 29 November 1919, lot 24 (undesignated consignor) — J. Robert Maguire

REFERENCE:

John P. Kaminski, et al., eds. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights XXXVII: Bill of Rights 1 (Madison, 2020); James F. Hrdlicka, Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions (New York: Scala, 2020); cf. Charlene Bangs Bickford & Helen E. Veit, eds., Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791 4 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986); cf. Neil H. Cogan, ed., The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins (Oxford University Press, 1997)

Sotheby’s is grateful to John P. Kaminski, Director, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for his generous assistance with this description.

You May Also Like

![[World War II – 21st Army Group] | An important archive of maps and files documenting the allied campaign in Europe, from the early stages of planning for D-Day and Operation Overlord, to the German surrender](https://dam.sothebys.com/dam/image/lot/f958941f-80a5-4c71-935b-c5441da85aa9/primary/extra_small)