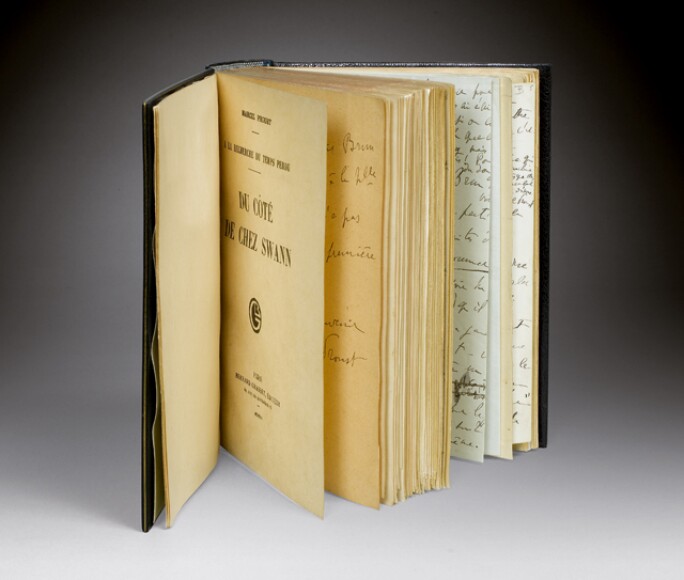

A rare copy of Marcel Proust's Du Côté de chez Swann will be offered for sale in the upcoming Livres et Manuscrits sale at Sotheby's in Paris on 30 October. This copy is a dream. It's number five, and the last of all the numbered copies printed on the finest Japan paper. Who was Proust thinking of when he dedicated this copy number five — his last copy on Japan paper? Let's think for a moment about the people to whom Proust didn't dedicate a copy on this kind of paper: Not his boyhood friend, Reynaldo Hahn, not his brother Robert, not his partner of the time, Alfred Agostinelli. It was to the company secretary of his publishing company.

MARCEL PROUST, DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ SWANN, PARIS, BERNARD GRASSET, 1913. ESTIMATE: €400,000—600,000.

Let's not imagine that Proust had numerous copies on Japan paper at home. Nothing of the sort. The copies on fine paper were printed after the copies on ordinary paper, a month later, in December 1918. The publisher kept them all apart from one, which Proust didn't keep for himself but dedicated to Lucien Daudet. So from the outset Proust only dedicated two copies out of five, to Lucien Daudet, his very dear old friend and, surprisingly, to the painter who was witness to his duel, Jean Béraud. That leaves the one belonging to Grasset, the one for the director of Le Figaro, Gaston Calmette, the one belonging to Louis Brun, which Proust didn't dedicate in 1913, because he didn't have them. Louis Brun, who no one remembers and who later had a tragic fate, the victim of a passion that is at the heart of the Recherche, jealousy. Proust wrote this dedication to him at a time when he had already left Grasset, not when he published his novel.

MARCEL PROUST, DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ SWANN, PARIS, BERNARD GRASSET, 1913. ESTIMATE: €400,000—600,000.

He took advantage of the fact to thank him for his efficient mediation and the response to his instructions, as revealed in the attached letters. It was probably Louis Brun who encouraged him to dedicate the book in 1918, shortly after being released from military service, accompanied by a letter like the one he would write to Proust in 1922 about Sodome et Gomorrhe II: "Taking advantage of your usual kindness, I (…) would be infinitely grateful to you if you would be so kind as to sign it, you would fill me with great joy." This joy on the part of the book-lover is not always incompatible with that of the investor, because from 1928 onwards Brun tried to sell his Swann and his other copies of the Recherche.

MARCEL PROUST, DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ SWANN, PARIS, BERNARD GRASSET, 1913. ESTIMATE: €400,000—600,000.

Louis Brun, an old friend of Bernard Grasset, was a brilliant assistant on whom the publisher, who was often ill and absent, relied completely. Grasset reveals this several times: "Fortune has smiled on me in allowing me to meet Brun at the start of my publishing career". He was "one of the most powerful factors in my success". Henry Muller also described him as an administrator polishing Grasset's initiatives or tempering his rage. With his 'assistant' Grasset would establish a kind of relationship of troubling perversity, combining affection, contempt, indulgence, meanness, mischief and generosity’. This whipping-boy for a boss who was always ill and depressive, with the physique of a discreet senior civil servant, also had the temperament of a pleasure-seeker, which would lead to his downfall. He had chosen bibliophilia among the pleasures of life and art.

MARCEL PROUST, DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ SWANN, PARIS, BERNARD GRASSET, 1913. ESTIMATE: €400,000—600,000.

First of all he drew at the source, from the authors at Grasset, keeping a limited edition, often marked in pencil with the inscription 'Louis Brun's copy', and dedicated where possible. When he sold his books in May and June 1942, the catalogue bore the note: 'Estate of M. Louis Brun', former director of Éditions Bernard Grasset, original modern editions signed by the author; the copies are in fact peppered with signatures. Grasset tried to oppose the sale, and writers such as Giraudoux, Mauriac and Morand would receive personal letters. Mme Brun wrote to Grasset in December 1942, asking him to oppose the sale: "It would be too long and too cruel for me to remind me of all the harm that you have done to my husband, whom I will always defend as a publisher". On 22 August 1939 she had murdered her husband in their villa on the Côte d’Azur, had thrown herself into the sea, been fished out and been acquitted. He had died for pursuing more than beautiful books.

MARCEL PROUST, DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ SWANN, PARIS, BERNARD GRASSET, 1913. ESTIMATE: €400,000—600,000.

The surprising thing, when we might imagine that he was floating far above the details and material life of the book, is the care with which Proust monitored the most concrete details of the edition: the price, the margins, the typographic characters, as well as the launch, the publicity, the press releases, all the stages of the manufacture and launch of a book. Before anyone else he understood the importance of communication, of publicity, of media relations. He wasn't miserly with his time or his money, not even shying away from what might look today like active corruption, paying newspapers to talk about his book and writing to tell them what they should publish.

Rather than locking himself away like Mallarmé in the 'cold dream of contempt', thinking the commerce is below him, he knows that he has little time to get his thoughts across, as if he were only their agent and they didn’t belong to him, that he was accountable to them in the eyes of public opinion and posterity. The correspondence that peppers this book bears the written trace of a new spirit, an adventurer in the industry of book-publishing, one of the first press attachés, of the ever-modern Marcel Proust.