A master of form, Pablo Picasso experimented endlessly with clay, pushing the boundaries of the malleable medium. This October Sotheby’s London is pleased to present an important single-owner collection of Picasso ceramics which surveys the incredible breadth of his terracotta creations, from the functional to the fantastical. Picasso: Master of Form honours the artist’s partnership with the esteemed Madoura pottery in Vallauris and celebrates his legacy as an artisan. Highlights of the collection that will be on offer include the grand Pichet à glace (A. R. 142) and abstract Grande tête de femme au chapeau orné (A. R. 518), alongside a selection of his sought-after gold and silver works, such as the exuberant Bacchante.

Sale Highlights

Chouettes

In 1946 while vacationing with Françoise Gilot in the South of France, Picasso met Georges and Suzanne Ramié, the owners of the Madoura pottery studio in the nearby town of Vallauris. The Ramiés welcomed Picasso into their workshop where the artist created three unique ceramic objects. This was the start of a friendship and creative partnership with the Ramiés that would last until Picasso’s death. He began working at Madoura daily, designing over 633 different ceramics between 1947 and 1971 that were to be made in editions of 25 to 500.

Owls feature widely across Picasso’s work, and they were inspired by an array of sources. First, the owl was the Greek symbol for Athena, the goddess of wisdom. The owl is also the ancient symbol of Antibes, the region neighbouring Vallauris, where Picasso worked on a series of paintings in 1946. It was during this time, while working at the Chateau d’Antibes, that Picasso discovered a wounded owl with an injured claw. He nursed the owl back to health, and though it was ill-tempered and bit at his fingers, Picasso developed a particular affection for the bird. He incorporated the motif into his vases, pitchers, plates and platters, often repeating certain forms and experimenting with different decorative effects.

There are several iterations of owls in this collection, including Petite Chouette (A. R. 82) (Lot 11), a small pitcher that was perhaps inspired by the artist’s owl companion. However, it is the vases that are especially distinguished in Picasso’s oeuvre (see lots 1-10), as whilst his other editioned ceramics were inspired by the forms of ancient pottery or Suzanne Ramié’s own designs, the Chouette vases are the only shapes designed by Picasso. With these sculptural, zoomorphic works, the artist uses volume as an integral element. Here, Picasso is concerned with proportions and a purity of form, creating an organic, living figure.

Edition Picasso

Dense, but pliable, clay offered Picasso endless freedom of expression. Enamoured by the playful medium, he explored a variety of ceramic techniques over three decades at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris. Together with workshop owners Georges and Suzanne Ramié, Picasso developed an impressive ceramic oeuvre ranging from practical bowls and ashtrays to fanciful, grand vases. Through this fruitful partnership, the artist discovered his two preferred methods of production: éditions Picasso – the process of replicating an initial design by hand alone – and eventually empreintes originales – editions incised by the artist that were then duplicated via plaster mould.

In surveying the éditions Picasso – each tellingly stamped or incised 'Edition Picasso' - one can trace the artist’s early mastery of the ceramic medium. He developed his personal style through trial and error, and quickly learned he preferred building by hand to wrestling with the wheel. He was bold but meticulous in his approach, being careful to round each pitcher and square each tile off just so before adding surprising flourishes, from luxurious slips and glazes to quirky handles. Even the expert potters at Madoura struggled to keep up with the prolific artist, who gracefully hand-crafted prototypes for vases as complex as the Vase deux anses hautes (A. R. 141) (Lot 31) and Vase au décor pastel (A. R. 190) (Lot 39) with ease.

Empreinte originale

In 1949, taking their inspiration from printmaking, Picasso and the Ramiés developed a method of producing editioned ceramics known as empreinte originale. To complete this process: a plaster mould was made of a plate, bowl or vase; once this had hardened, Picasso would carve into or model onto the material to delineate an image. A sheet of prepared clay was then pushed down into the mould to take an impression of the design. Picasso’s compositions thus appeared in reverse – his incised lines became areas of relief, as in Tete au Masque (A. R. 362) (Lot 92) and Visage au nez pincé (A. R. 440) (Lot 95), while relief that had been added to the mould resulted in engraved voids and recesses.

From the mid-1950s, Picasso began to leave some of his large empreintes undecorated by glazes or slips – these were called the pâtes blanches. Georges Ramié described this series of works as follows: ‘white or pink biscuit-fired earthenware, engraved in relief, preserving all the freshness they possessed as they were removed from the matrix, without being worked over. In this way they satisfy sculpture’s need for light, which alone can provide it with truth and life.’ (McCully, p. 33)

Sculptural vessels

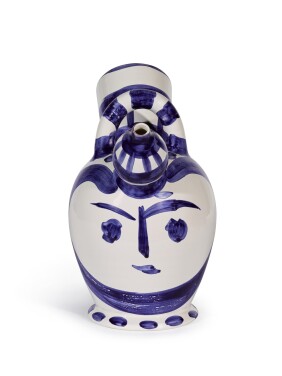

Picasso turned to ceramics later in life, building upon his knowledge of painting and sculpting to create masterful portraits and abstract designs in the round. He dreamed of creating forms that would serve a useful purpose in daily life while maintaining artistic merit; vessels that would straddle the line between functional and fashionable. On his quest to create a work of art that would be of use to every household, the artist re-imagined standard containers such as jugs and vases, re-interpreting their portly and voluptuous shapes as bearded satyrs or idyllic nudes.

Inspired by the mystique of Southern France and the ancient potters that once inhabited Antibes and Vallauris, Picasso updated their classical forms with cheerful hues and unexpected englobe decoration. In his hands, the narrow lekythos transformed into the sylphlike Femme (A. R. 297) (Lot 47), while the curved askos appears to have inspired the plump Sujet poule (A. R. 250) (Lot 50). He also introduced new forms, such as the Pichet à glace (A. R. 143) (Lot 30), a characterful ice pitcher painted in classic blue and white – the perfect companion during sweltering days along the Côte d'Azur.

Linocuts

While in Vallauris in the late 1950s, Picasso began to work with the master printer Hidalgo Arnéra on a printmaking technique that was then novel to him: the linoleum cut. The artist and printer initially collaborated to create linocut posters advertising local events. These early projects focused Picasso’s attention on the graphic possibilities of the medium, which he continued to explore throughout his practice in the 1960s.

This collaboration with Arnéra soon led Picasso to a new objective: to recreate his linocuts as ceramic tiles or plaques. To realise the idea, Picasso used his linoleum blocks to model an intermediate plaster matrix; then, following the empreinte originale process, sheets of clay were impressed into the moulds to create editions of earthenware tiles. When the tiles had set, dense areas of black slip were applied to the surfaces, contrasting intensely with the red clay beneath – the resulting objects thus recall the stark and dramatic colouring of the prints from which they were derived.