T his April Sotheby’s presents a new sale filled with elegant Silver, Porcelain, Russian Works of Art and Objects of Vertu to adorn the most stylish of Easter tables. As the early signs of Spring begin to bloom, our thoughts naturally turn to flora and fauna that craftsmen and women have celebrated in art and objects for centuries. Inspired by the bounties of Spring, this sale focuses on rare and unusual finds such as a Victorian silver and enamel cruet set with salts and a pepperettte in the form of speckled eggs, to a set of eighteen modern French silver charger plates by Puiforcat in pristine condition. The Porcelain and glass section includes dinner, dessert and glassware services from famous factories such as Royal Copenhagen, Herend, and Baccarat. A group of seven porcelain Easter eggs from the Imperial Porcelain Factory in St. Petersburg would be a colourful addition to any table, whilst the Vertu section includes more bijoux treasures such as a solid gold pill box in the form of a frog by Tiffany & Co., Paris. With estimates from £150-£30,000 the sale comprises an exciting range of objects to liven up any basket or table at Easter.

Sale Highlights

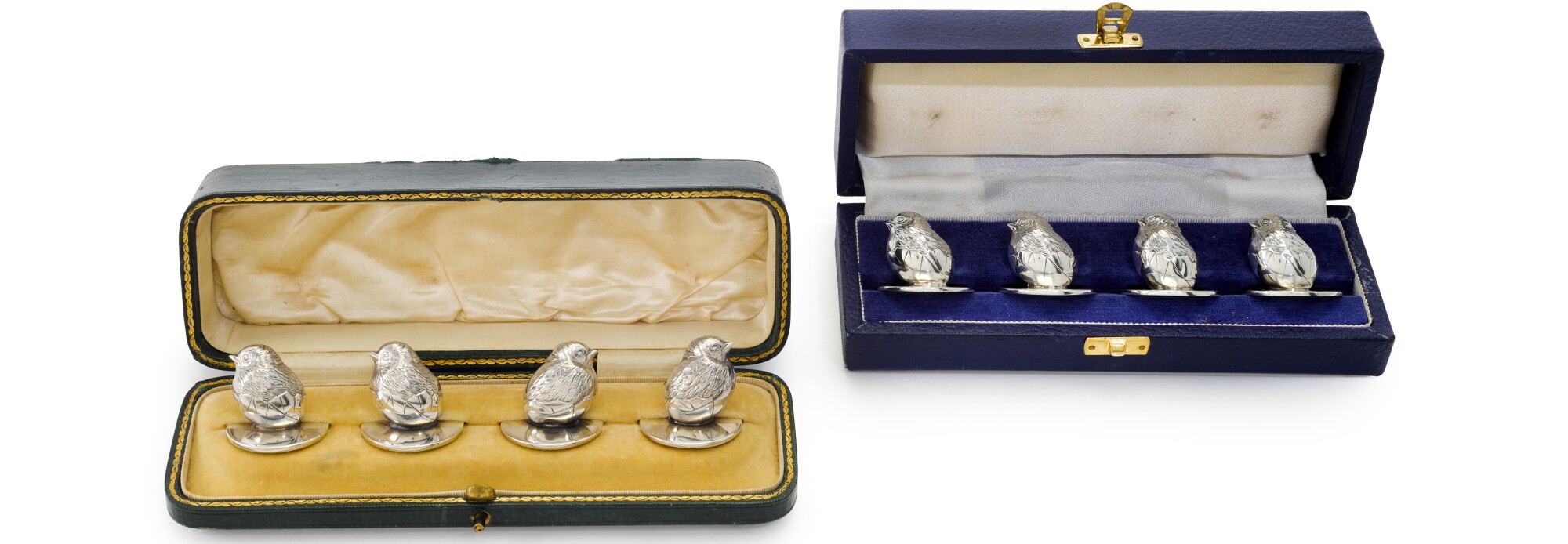

It would appear that menu holders were generally unknown before the 1860s. In an age of luxury, when great attention was paid to the landscape of the luncheon or dining table, an attentive hostess was never insensible to the latest fancy or a way to add charm to her select gatherings. Manufacturers of ceramics were probably the first to create special stands for menus: Thomas Goode & Co. of South Audley Street, when commissioned to provide the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh's State Dessert Service in 1865 included among the auxiliary pieces, '24 compotiers, eight fruit and flower baskets, beautifully perforated, and supported by admirably modelled parian cupids, and four jardinières, [and] 18 cupid menu holders, a new design and novelty in the service.' (The Standard, London, Friday, 1 September 1865, p. 3e)

Maud C. Cooke, in her book, Social Life; or, The Manners and Customs of Polite Society, however, had a word of caution for the over-eager: 'Menu holders are frequently very pretty, and upon the menu card itself much taste and expense are sometimes lavished. Still it is not considered good taste to have them at every plate, for the reason that it savors too much of hotel style.' (Buffalo, New York, 1896, p. 196) But with so many delightful designs which soon became available, it must have been difficult to resist the latest trifle, especially when fashionable shops vied with each other to present all the best novelties. 'Indeed,' wrote one journalist, 'a lady must be exceedingly stupid . . . who could not arrange a model dinner-table with such material.' In 1873, John Mortlock & Co. in Orchard Street, London, displayed 'little China' menu holders formed as 'butterflies with wings erect [which] answer better for single cards.' These, according to the same report, were in accordance with Mortlock's model dinner-table, which had been 'laid out by a lady considered to be an authority on such matters.' ('Metropolitan Gossip. From our own correspondent. London, The Belfast News-letter, Belfast, Thursday, 10 July 1873, p. 3a)

Not to be outdone, the silversmiths gathered their resources and soon a bewildering number of menu holders were available in the precious metal whose patterns ranged from simple scrolled wirework to the colourfully enamelled. The designs of many were protected by law, in the case of the present S. Mordan & Co. Ltd. hatching chicks and fishes, under the provisions of the United Kingdom Patents, Trade Marks and Designs Act of 1883. In fact, chicks were a favourite subject for menu holders as well as other silver novelties; they made perfect wedding presents. In 1885 the Countess of Wharncliffe gave to Dulcibella, eldest daughter of Lord Auckland of Edenthorpe on her marriage 'a silver chick muffineer [pepperette] and a silver-mounted fish scent-bottle.' Then in 1911 we read that, 'Amongst the newest items are the little silver chicks carrying velvet pin-cushions on their backs.' (Yorkshire Gazette, York, Friday, 2 January 1885, p. 4e; The Warwick & Warwickshire Advertiser, Warwick, Saturday, 2 December 1911, p. 2b)

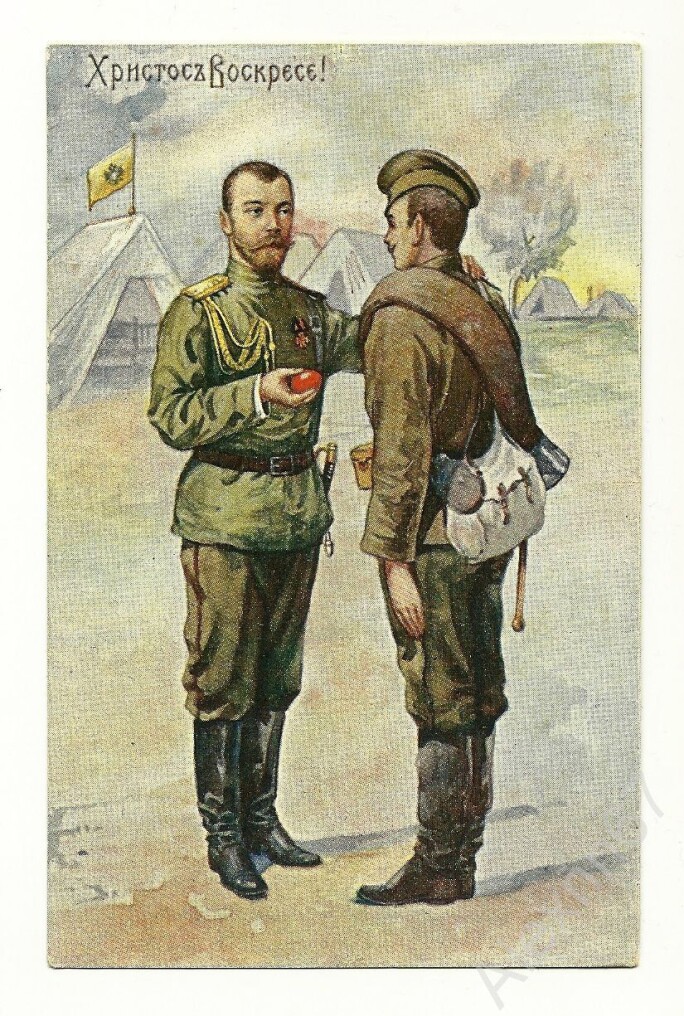

Easter, the ‘Feast of Feasts’ in Imperial Russia, was truly the most joyous and important holiday of the Orthodox calendar. Romanov Emperors would traditionally present gifts not only to their families but also to a wider circle. Such celebrations would manifest themselves in gifting elaborately decorated eggs and would sometimes last for a few days. This was an opportunity to feel Christian union between the Emperor and his people.

Eggs symbolised life: a painted egg, originally in red - the colour of Christ’s blood - would become the most significant and long-lasting symbol of this major celebration. From the very early days, the Imperial Porcelain Factory started manufacturing painted porcelain eggs, which became a truly Russian phenomenon. In 1749, the founding father of the Imperial Factory - Dmitry Vinogradov - famously presented Empress Catherine the Great with the first porcelain Easter egg, establishing this tradition.

In 1885, Alexander II presented his Guards Regiment with painted porcelain eggs decorated with Imperial monograms. Such eggs painted in different colours and decorated with Imperial crowns were very popular during the reign of Alexander II and Nicholas II. However, it was really the Easter eggs commissioned for Empress Maria Feodorovna and decorated with blossoming bouquets and individual flowers that gave way to elaborate new designs and colour palettes. The Imperial Porcelain Factory was already producing over 2,000 eggs each Easter during the reign of Alexander II. The number increased to 5,000 by the time Nicholas II reigned the Empire. Eggs painted with images of Saints were amongst the most sought-after gifts, and could take up to forty days to be produced. Exquisite, finely painted porcelain floral Easter eggs, decorated with tinted gold of different shades, became generous and beautiful gifts, favoured by the Imperial family.

Porcelain Easter eggs were always made to be suspended by ribbons. Two holes at each end would allow for silk or velvet ribbons to be threaded through, terminating with a bow at the bottom and a loop at the top. The Imperial Factory had a specialised department of so-called ‘Bow Women’, hired specifically for this job. Eggs were suspended from an icon or kiot.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the gifting of Easter eggs had become almost a secular tradition, and the porcelain egg itself became an expensive and refined work of art.

The development of porcelain for use and for show is intertwined with the evolution of elegant dining habits and entertaining in the aristocratic houses of Europe. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries the way society’s elite dined changed; the fashion was set by the French court with service à la française, where a variety of dishes were served at the same time, usually on a buffet. The less formal service à l’anglaise, served by your hosts at the head of the table was also popular. By the 19th century the service à la russe, where place settings and separate courses were brought by servants became something which might seem more familiar to us today in formal and restaurant dining. Today we are used to seeing porcelain services from the finest makers which cater for each stage of a meal from start to finish (see lots 49 and 75) .

Banqueting and dining evolved in Europe during the Renaissance with the introduction of exotic imported ingredients, notably with the use of sugar which was as much a status symbol as a flavouring. Whilst sweetened seeds and nuts and candied fruits have been popular for centuries, sugar and cream were used to embellish meat and fish. The separate dessert course becomes popular from about 1600 onwards and it is common to see dessert wares listed as part of 18th century porcelain services. With the introduction of the Russian style of service by the early 19th century, porcelain factories began to produce elaborate services which were distinct from the main banqueting service (see lot 102). As the century progressed this became the mainstay of many factories who would produce small elegant services for their clientele to use in their salon as well as more formal occasions (see lot 100) .