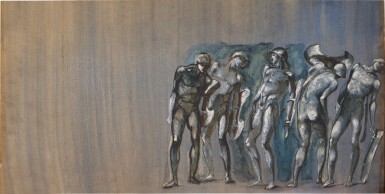

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt., A.R.A., R.W.S.

Phineus and his courtiers turned to stone

Estimate

50,000 - 70,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones

(Birmingham 1833 - 1898 London)

Phineus and his courtiers turned to stone

Point of the brush and brown wash with watercolor and white gouache on paper washed blue

333 by 650 mm; 13⅛ by 25⅝ in.

The studio of the artist,

sale, London, Christie’s, ‘The Remaining Works of the Late Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Bart’, 5 June 1919, lot 148;

Albert Kantor,

his sale, London, Sotheby’s, Belgravia, 25 March 1975, lot 25;

sale, London, Sotheby’s, 9 June 1998, lot 30;

with the Maas Gallery, London, British Pictures 1840-1940, 1998, no. 31;

with Thomas Williams, Old Master Drawings, 1999, no. 39,

where acquired by Diane A. Nixon

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum; Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Private Treasures: Four Centuries of European Master Drawings, 2007, no. 88 (entry by Stacey Sell)

As a draughtsman Edward Burne-Jones is best-known for his exquisite pencil or chalk studies of women’s heads, drawn with delicacy and precision. In this remarkable watercolor sketch we see something far darker, visceral and pained – more modern in its uncompromising depiction of the human form recoiling in agony. As though hewn out of stone, the male nudes are frozen and heavy – completely appropriate for the subject of the soldiers of Phineus literally petrified by the sight of the severed head of the Gorgon, Medusa. Although painted more than a century and a half ago, circa 1876, the figures have the contorted monumentality of artists like Henry Moore or Edward Burra, whilst also demonstrating the inspiration from Luca Signorelli’s frescos at Orvieto, the marmoreal agony of Michelangelo’s Slaves and Phidias’ Parthenon metopes.

This sketch is one of many preparatory studies made for what was to become Burne-Jones’ greatest unfinished project – the decoration of the music room of the rising Conservative politician Arthur James Balfour’s house at 4 Carlton Gardens. It was not simply a decorative commission, it was an obsession, sometimes overwhelming and one into which Burne-Jones poured his often pessimistic, agonized imagination. Balfour had met Burne-Jones in around 1871 and ‘at once fell a prey to the man and his art.’1 It was not until 1875 that Burne-Jones began the cycle of paintings and gesso reliefs. The decorative scheme that he devised told the story of the Greek hero Perseus, retold by William Morris in his poem ‘The Doom of Acrisius’ which formed part of the Earthly Paradise. The scenes depicted Perseus called to a quest to slay the cursed Gorgon Medusa and to rescue the beautiful Princess Andromeda from the claws of a sea-monster. These scenes were all noble depictions of courtly-love but the penultimate scene revealed a more sinister aspect of romance and betrothal. The Court of Phineas depicts Perseus brandishing the severed head of Medusa to turn the followers of King Phineas to stone so that Perseus could marry Andromeda who had previously been betrothed to Phineas. The dubious nature of the justification for this act may not have been so simple for Burne-Jones, a man who was partial to falling in love with the wives of other men.

The passage in Morris’ poem that Burne-Jones intended his gesso panel to depict describes how the courtiers of King Phineas arrived at Perseus and Andromeda’s wedding ceremony, bursting into the hall in a jealous rage;

‘Then all set on him with a mighty cry;

But, with a shout thrilled high over theirs.

He drew the head out by the snaky hairs

And turned on them with baleful glassy eyes;

Then sank to silence all that storm of cries

And clashing arms, the tossing points that shone

In the last sunbeams, went out one by one

As the sun left them, for each man there died.

E’en as the shepherd on the bare hill-side,

Smitten amid the grinding of the storm,

When while the hare lies flat in her wet form

E’en strong men quake for fear in houses strong,

And nigh the ground the lightning runs along.

But upright on their feet the dead men stood;

In brow and cheek still flushed with angry blood:

This smiled, the mouth that was open wide,

This other drew the great sword from his side,

All were at point to do this thing or that.’

The Court of Phineas was originally intended to be made in gesso relief and painted gold for a panel above the doorway in the music room. It was one of twenty-two scenes that Burne-Jones identified as being ones he could realize, described as ‘Phineus bursting into the hall. Perseus showing the head.’ A gouache in the collection of Tate, London depicts the last four projected panels (including The Court of Phineas) and their positions in Balfour’s music room.2 Although Burne-Jones began panels of at least ten of the scenes the project was ultimately abandoned. Burne-Jones made a large number of detailed figure drawings for The Court of Phineas (for example in sketchbooks at Birmingham City Art Gallery and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) but no panel was ever begun. A sketchbook in the collection of Birmingham City Art Gallery contains studies of male nudes for The Court of Phineas, and like the present sketch, they demonstrate Burne-Jones’ view; ‘… the fine thing about a man is that he is such a splendid machine, so you can put him in motion, and make as many knobs and joints and muscles about him as you please.’ 3

1.A.J. Balfour, Chapters of Autobiography, London, 1930, p. 233

3.Quoted in Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials, vol. 2, p. 269)

You May Also Like