Gian Lorenzo Bernini

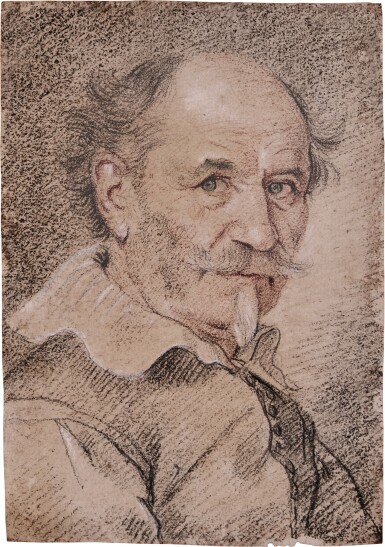

Portrait of a man with mustache and pointed beard

Estimate

80,000 - 120,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

(Naples 1598 – 1680 Rome)

Portrait of a man with mustache and pointed beard

Black, red and white chalk, on buff paper

207 by 144 mm; 8⅛ by 5⅝ in.

Private collection, Florence, until 1892;

K. Kendall, 1892,

thence by inheritance to his widow, Mrs. K. Kendall;

presented to Sir Herbert Conyers Surtees (1858-1948), Mainsforth Hall, County Durham, in 1917,

thence by descent to his daughter, Lady Bertha Dodds;

sale, London, Sotheby's, 21 May 1963, lot 671 (to Bossier);

Private collection;

sale, London, Sotheby's, 30 October 1980, lot 127 (as ascribed to Bernini);

Private collection, Belgium;

with Day and Faber Ltd., London, 2001,

where acquired by Diane A. Nixon

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum; Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Private Treasures: Four Centuries of European Master Drawings, 2007, no. 32 (entry by Rhoda Eitel-Porter);

Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College Museum of Art; Ithaca, New York, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Drawn to Excellence: Renaissance to Romantic Drawings from a Private Collection, 2012-2013, no. 40

A. Weston-Lewis, Effigies and Ecstasies, Roman Baroque Sculpture and Design in the Age of Bernini, exhib. cat., Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland, 1998, p. 60, reproduced fig. 46, under no. 15;

N. Turner and R. Eitel-Porter, Roman Baroque Drawings c. 1620 to c. 1700: Italian Drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, London 1999, vol. II, under no. 14;

A. Sutherland Harris, ‘Bernini’s portrait drawings: context and connoisseurship’, in Sculpture Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, 2011, pp. 174-175; reproduced p. 177, fig. 18

Portrait drawings constitute unquestionably the most intimate element in the artistic output of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the genius of the Baroque. A very special group, executed, like his academic figure studies, from life, they were made in their own right as independent works, to be given to relatives and friends. These portraits, mostly in a head-and-shoulders format, are never conventional, and reflect spontaneous and informal, but always acute, observation.

Beautifully animated by his oblique and expressive gaze, the present sitter, like those in the majority of Bernini's portraits, has not yet been identified. With penetrating characterization, he engages the viewer with directness, devoid, as in all the drawn portraits, of any of the official grandeur of the artist’s sculpted works. Bernini is focusing here on the subtle and refined description of the face, set off and framed by the irregular curls of the hair. The irregular contours of the hair, together with the rendering of the mustache and goatee beard, demonstrate the artist's attention to the creation of a sense of motion and vitality, like in his sculpted portraits. Ann Sutherland Harris has, indeed, stressed that ‘Making portrait drawings helped Bernini to make better portrait busts'.1

As Aidan Weston-Lewis described in his informative essay on 'Portraits of Bernini, Portrait Drawings and Caricatures' (see Literature), about twenty-five such portrait drawings by Bernini are known today, including a number of self-portraits, but interestingly not one of these is the likeness of a woman, though it appears that a drawing by Bernini of his wife did once exist.2 Weston-Lewis, supported by Sutherland Harris, has associated the Nixon drawing stylistically with a portrait of a young boy in the British Museum, and tentatively dates both to the mid-1630s, while acknowledging that it is not easy to establish exactly where these sheets fit in the sequence of Bernini’s portrait drawings.3 The British Museum drawing is executed in the same chromatic media, à trois crayons, and though its attribution to Bernini was at first questioned by Sutherland Harris, she has since revised her opinion (see Literature). Like Weston-Lewis, she has also highlighted the difficulty in establishing a dating for these two drawings, pointing out that the form of the present sitter’s collar might indicate a date around the 1610s or 1620s, but conversely the lack of tabs along the join between sleeve and jacket fits better with a dating in the 1630s. Francesco Petrucci has also kindly suggested a dating of 1630-1640.4

A further footnote regarding the possible identity of the sitter derives from a pencil inscription on an old mount, now lost, which identified this as a portrait of the artist Pietro da Cortona, but as Rhoda Eitel-Porter noted in 2007 (see Exhibited), this suggestion cannot be substantiated. Pietro da Cortona's painted self-portrait in the Uffizi, Florence, depicts a man with a similar mustache and goatee, but his brow is straighter, his chin more pointed, and his jowls heavier; it is difficult to imagine him as the same person represented here. A second inscription, on the verso of the old frame, refers to the drawing as a self-portrait by Bernini, which is also not borne out by a comparison with known likenesses.

Not surprisingly for an artist whose career spanned some seventy years, the drawings of Bernini show great technical and stylistic diversity, although his preferred media for portrait drawings is the combination of black, red and white chalks that we see in the Nixon sheet. This same technique is found in some of Bernini's greatest portrait drawings from the middle years of his career, such as the portrait of Sisinio Poli, dated 28 April 1638, in the Morgan Library and Museum, which Eitel-Porter compares with the Nixon drawing, noting that the sitter sports a similar large white collar and doublet.5

1.Sutherland Harris, op. cit., p. 163

2.Weston-Lewis, op. cit., p. 47, p. 201, note 1

3.London, British Museum, inv. no. 1980,0126.69; Ibid., p. 60

4.E-mail dated 20 November 2025

5.New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, inv. no. IV, 174

You May Also Like