Property from Jack Kilgore & Co., New York

FERDINAND KNAB | ROMAN RUIN AT TWILIGHT

Lot Closed

June 25, 03:21 PM GMT

Estimate

50,000 - 70,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from Jack Kilgore & Co., New York

FERDINAND KNAB

Würzburg 1834 – 1902 Munich

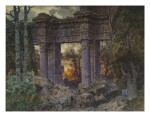

ROMAN RUIN AT TWILIGHT

signed, dated, and inscribed at lower right corner: F. KNAB/ Munchen 1894

oil on canvas

unframed: 39½ x 51⅛in.; 100 x 130 cm.

framed: 50¼ x 62¼ in.; 127.6 x 158.1 cm.

Anonymous sale, Stuttgart, Nagel Auktionen, 28 June 2006, lot 192;

Private Collection, United Kingdom.

"This is an imposing painting because of its scale, and the subject matter is equally arresting. We see Roman ruins (probably derived from the Baths of Caracalla) cast in a twilight atmosphere and creating a purple haze over the decaying monuments. I suggest that the interested bidder blow up the image to the max and concentrate in the bottom center of the composition, where a surprise awaits."

Otto Naumann

Although sometimes called an “academic painter” Ferdinand Knab was actually a very poetic artist in the romantic vein who specialized in the depiction of ruins and architectural fragments. Born in Würzburg, he initially trained in architecture in Nuremberg and then went to Munich in 1859 where his professors at the Academy were the well-established realistic masters of history painting, Arthur von Ramberg and Carl Theodor von Piloty. In 1860 his painting Patrician Court was exhibited by the Munich Art Association, and it was followed by several other successful showings. He was then able to gain a residency in Italy during 1868. It was this journey that revealed to Knab the scenic beauty of crumbling ruins set in picturesque landscapes. Like the great German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who visited Italy in 1786-88 and published his Italian Journey in 1816-17, Knab was enthralled by the wonders of Italian ruins, and his study of Roman antiquity took him, like Goethe, as far south as Taormina in Sicily.1 Goethe made his own highly romantic drawings in Italy2 and was accompanied in Sicily by the German painter Christoph Heinrich Kniep (1755-1825) who produced scenes of ruins and grottos some of which were used to illustrate Goethe’s book.3 After his return to Germany, Goethe created his own mock ruin at Weimar, and Knab, following his return drew on his memories to paint detailed treatments of ruins, real and imagined, set in scenic landscapes for the rest of his career.4 These subjects made Knab well known. King Ludwig II of Bavaria, famed as the patron of Wagner, named him a royal court painter and commissioned decorative works and plans for his Munich Residenz and the Linderhof Palace.5 Knab also produced set designs for a production of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute in 1870. And in 1886 he created a series of color engravings devoted to recreations of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.6 The taste for scenic Roman ruins in Italy and Greece had been established already in the eighteenth century by such visiting French artists as Hubert Robert, sometimes referred to as “Robert des Ruines,” whose work was extremely popular in Germany. A number of Robert’s drawings such as The Temple of Augustus at Pula, Archaeologists at the Temple of Vespasian, and even a Capriccio of the Portico of the Pantheon all with their elaborate Corinthian columns supporting a heavy pediment are certainly antecedents of Knab’s temple.7 Even more readily available would have been Robert’s series of etchings of Evenings in Rome published in 1763.8 The decorative artist Charles-Louis Clérisseau (1721-1820) also produced inventive depictions of Roman ruins. And of course the Italian printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) had created many etchings of the picturesque ruins in Rome and its surroundings (figs. 14-16). These undoubtedly were known to Knab, as would have been period photographs of Italian ruins. There was, in fact, a tradition of earlier German artists of the nineteenth century, such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Leo von Klenze, being drawn to the subject of ancient classical ruins. The “quintessential” German Romantic painter of the nineteenth century, Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)9, never went to Italy, but he or his friend, Friedrich Carus, inspired undoubtedly by prints, painted a striking scene of the ruins at Agrigento. Friedrich also produced several romantic depictions of ruins and tombs at his favorite time of day – dusk.10

The impressive temple which is the centerpiece of this painting has not been identified, and is probably Knab’s own creation. In an inventive pastiche he combined massive Corinthian columns supporting a plinth with a frieze of sculpted figures. Perhaps, with his architectural skills, he actually constructed a model of this temple, so he could study it in the round. The artist, obviously fond of his creation, repeated it from different angles in several other works. Sometimes it appears by a river’s edge;11 and sometimes as a vertical composition with Böcklin-like cypress trees, as well as birds or additional sculptural fragments.12 In the present example the natural elements are not so benign. At the lower center an eagle or falcon with outstretched wings attacks a rearing snake. This was a traditional symbolic representation of opposites battling and may suggest that amidst these crumbling ruins at sunset there is an eternal conflict of life and death being waged. A possible prototype for this occurred in an early painting by Caspar David Friedrich of the Chasseur in the Forest with a single ill-omened, black bird highlighted at the center. Just like Friedrich, Knab’s work reveals his interest in transience and death. Here in addition to the animals struggling for survival, there is a notable contrast between the bare trees on the left and the flourishing cypress on the right. The cypress, through its association with cemeteries and mourning, was a symbol of death. Thus this memorable landscape with ruins is fraught with symbols of decay. Knab powerfully depicts a silent world of the past, with the setting sun casting a reflected glow on the ancient structure. It is a haunting reverie, which reminds one of Goethe’s poetic description of the ruined Temple of Segesta in Sicily:

The site of the temple is remarkable...it towers over a vast landscape, and only a small corner of the sea is visible. The countryside broods in a melancholy fertility...The wind howled around the columns as though they were a forest, and birds of prey wheeled screaming above the empty shell.

1. Painted in 1870 and sold at Sotheby’s, Amsterdam, October 16, 2007, no. 100; and at Lempertz, Cologne, November 17, 2012, no. 1532.

2. See Paolo Chiarini, Goethe in Sicilia, Gibellina, 1992, fig. 56.

3. See Georg Striehl, Der Zeichner Christoph Heinrich Kniep (1755-1825), Hildesheim, 1998, ills. 87, 91-92, 128, 146, and 196.

4. See Christies, London, sale December 1, 1989, no. 45; and Ketterer Kunst, Munich, sale May 14, 2011, no. 129.

5.See the exhib. cat. König Ludwig II und Die Kunst, Munich Residenz, 1968, pp. 185, 197, and 220,

6. Published in the Münchener Bilderbogen.

7. See Les Hubert Robert de Besançon, Besançon, 2013, no. 109.

8. See the recent exhibition catalogue Hubert Robert, National Gallery, Washington, D. C., 2016, nos. 23, 32, and 40.

9. See Joseph Leo Koerner, Caspar David Friedrich And The Subject of Landscape, New York, 1990, p. 29.

10.See Norbert Wolf, Caspar David Friedrich: The Painter of Stillness, Cologne, 2012, pp. 69 and 70.

11 Another dated also 1894 was sold at Rieber, Stuttgart, March 29, 2001, no. 862 and again April 4, 2001, no. 862. Most similar to the present painting is the 1886 painting sold at Nagel, Stuttgart, September 21, 2006, no. 1841. A vertical composition of 1898 is illustrated on Wikipedia from the Düsseldorfer Auktionhaus. Another was sold at Kunstauktionhaus Schloss Ahlden GmbH, Ahlden, September 15, 2007, no. 1666 and a vertical one at the same venue on September 13, 2009, no. 1457.

12. One of 1888 in a private collection; and one of 1898 sold at the Düsseldorfer Auktionhaus. 18 Koerner, 1990, pp. 193-4 and 182, fig. 74. 19 J. W. Goethe, Italian Journey (1786-1788), translated by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, New York, 1962, p. 255.