Property from Galleria Porcini, Naples

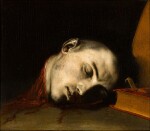

JUSEPE DE RIBERA, CALLED SPAGNOLETTO | THE SEVERED HEAD OF SAINT JANUARIUS

Lot Closed

June 25, 01:49 PM GMT

Estimate

80,000 - 120,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Property from Galleria Porcini, Naples

JUSEPE DE RIBERA, CALLED SPAGNOLETTO

Játiva, Valencia 1591 - 1652 Naples

THE SEVERED HEAD OF SAINT JANUARIUS

oil on canvas

unframed: 41 x 47.2 cm.; 16⅛ x 18⅝ in.

framed: 70 x 76 cm.; 27⅝ x 29⅞ in.

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here

Possibly Giuseppe Carafa, Duke of Maddaloni, by 1648;

Florence, private collection.

M. Niola, 'Naples: démesure pour mesure', in M. Hilaire and N. Spinosa (eds), L’âge d’or de la peinture à Naples. De Ribera à Giordano, exh. cat., Paris 2015, pp. 218–19, reproduced fig. 4;

G. Porzio, in D. Dotti (ed.) Il silenzio delle cose. Vanitas, allegorie e nature morte da collezioni italiane, exh. cat., Turin 2015, pp. 195–96.

"Such a direct image perfectly encapsulates the Caravaggesque idiom, which Ribera was to develop so successfully. The unexpected and novel blend of unhindered realism with the violence of Counter-Reformation iconography are as powerful today as they would have been in mid-seventeenth-century Naples."

Edoardo Roberti

Displaying the head of Saint Januarius, the patron saint of Naples, on a bare stone or, more often, on a plate, as if it were a still life, is a motif that goes back to the Italian region of Lombardy, where Saint John the Baptist’s severed head was often represented in this way. It is likely to be no mere coincidence that the earliest example of this type of iconography comes from Caravaggio’s time in Naples. This image is known from a painting executed by an artist in Caravaggio’s circle, often thought to be Louis Finson, depicting Saint Januarius showing his own relics, now in the Palmer Museum of Art.1 This devotional image, in which one finds the saint’s index finger, severed by the executioner during the beheading, in addition to his mitre and the vials containing his blood, most likely developed during the soaring popularity of the saint's cult in Naples after the eruption of Vesuvius in 1631, whose interruption was attributed by the devout populace to the miraculous intervention of their patron saint. An early, very graphic depiction of the theme is to be found in a canvas by Battistello Caracciolo at the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.2 Although the present painting lacks a signature (which anyway in Ribera’s case would not necessarily be a guarantee of authenticity), the quality of the work strongly suggests his authorship. The composition, more violent than Battistello’s (which comes as no surprise, knowing Ribera), is unique in his catalogue, which instead includes several heads of John the Baptist—among them one now in a private collection in Naples (fig. 1) and another, better known, in the Museo Civico Filangieri in Naples, dated 1646 3—along with no less notable images of Saint Januarius, including the full figure hovering above the city in the monumental retablo de Las Agustinas of Salamanca, first documented in 1636 (fig. 2) and a half figure dated two years later, in a private collection in Naples.4 It is quite fitting to cite these two canvases here, given the close affinity between the physiognomies of the saint and the type used by Ribera in the present painting; furthermore, they share an offhandedness and incisiveness which suggests that they painted around the same moment.

Sources known to date mention only one ‘head of St Gennaro by the hand of Gioseppe [sic] Rivera’, registered in 1648 and 1649 in the post mortem inventories of the picture gallery of Giuseppe Carafa of the Dukes of Maddaloni.5 In the latter entry the dimensions of the painting are indicated, ‘three palms by two and one-half palms’, including the ‘[carved and] gilded frame’. Curiously enough, Carafa met with the same gruesome fate: he was decapitated, together with his elder brother Diomede, for having attempted to assassinate Masaniello during the 1647 revolt.6

In conclusion, the very singularity of the theme in Ribera’s vast corpus, the harmonious format, and the excellence of execution appear to be weighty arguments in favour of identifying the present painting as the very same one which once belonged to Carafa.

Giuseppe Porzio

The attribution to Ribera has also been independently endorsed by Professor Nicola Spinosa and Dottor Gianni Papi.

1 Inv. no. 918. See J. Spike, Caravaggio, New York and London 2001, CD-ROM, pp. 432–33, 90.

2 Inv. Reg. Cron. no. 2338; S. Causa, Battistello Caracciolo. L’opera completa, Naples 2000, p. 185, no. A44.

3 For the example in a private collection (formerly Christie’s, London, 6 July, 2006, lot 48, sold for £250,000), see N. Spinosa, Ribera. La obra completa, Madrid 2008, p. 446, no. A292; for the Filangieri painting (inv. no. 1455) see G. Porzio, in Caravaggio e il suo tempo, exh. cat., San Secondo di Pinerolo 2015, pp. 142–43, no. 32.

4 The best reproduction of this painting, sometimes mistakenly thought to represent Saint Pantaleon, is in A.E. Peréz Sánchez and N. Spinosa (eds), Jusepe de Ribera. El Españoleto, exh. cat., Barcelona 2003, p. 119. For a synthetic discussion of the more famous Spanish canvas, see Spinosa 2008, p. 406, no. A195.

5 The Getty Provenance Index® Databases, docs. I-39, no. 56, and I-752, no. 3.

6 R. Villari, 'L’uccisione di Giuseppe Carafa', in S. Rota Ghibaudi and F. Barcia (eds), Scritti politici in onore di Luigi Firpo, II: Ricerche sui secoli XVII–XVIII, Milan 1990, pp. 323–28.