Clara Schumann. 215 unpublished letters to the composer and environmentalist Ernst Rudorff, with his replies, 1858-1896

This lot has been withdrawn

Lot Details

Description

SCHUMANN, CLARA

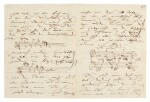

Important series of 215 unpublished autograph letters, cards and letters signed, to the composer, conductor, pianist and environmental pioneer Ernst Rudorff, together with his side of the correspondence, largely complete, 1858-17 January 1896

1) CLARA SCHUMANN'S LETTERS TO RUDORFF, reporting Brahms’s visits and early performances of his works over four decades, her concerts and tours in Russia, England and Vienna, making arrangements for her concert in Berlin in 1883 (conducted by Rudorff), seeking his advice about the Complete Schumann Edition (requesting copies of the first editions, to check proofs, fingering and letters), asking Rudorff to buy Schumann’s autograph of the Second Symphony from Albert Rietz, discussing Joachim’s estrangement from his wife and from Brahms, denouncing Wagner’s music and his “Schmähschrift” against the Jews (whilst welcoming Eduard Hanslick's articles on Bayreuth), discussing the virtues of different pianos (Érard, Blüthner, Steinway), and criticizing Carl Tausig’s fingering system, sharing her constant worries about her children’s education (requesting him to teach Felix and Eugenie), their illnesses and her search for positions or accommodation for them, opining on Rudorff’s compositions (she played his Variations op.1 in Vienna), falling out over teaching her student Nathalie Janotha, reporting her studies of Schubert’s Sonata in G op.78 and Chopin’s Piano Concerto no.2 (which she had not played for thirty years), and exchanging news about her colleagues at the Hoch Conservatorium in Frankfurt (Hiller, Raff, Stockhausen & Scholz) and Hermann Levi, Pauline Viardot, commenting on Max Bruch’s Hermione, her increasing suffering from rheumatism, arthritis, phlebitis, tinnitus, loneliness and depression, her visits to spas at Baden-Baden, Berchtesgaden and Interlaken, and many other matters

c.650 pages, mainly large 8vo (up to c.22.5 x 14cm), some up 8-12 pages long, written in dark brown and blue ink, including around 35 letters dictated by Clara to her daughters (mainly Marie) and signed by her, some addressed to Rudorff's mother Betty and to his wife Gertrud, a few autograph musical quotations (Paganini's theme used in Brahms’s Variations op.35), most written on "hand-made" paper, some on postcards, one short note in blue crayon, embossed or printed initials, over 40 autograph envelopes, one note about Joachim written on an envelope, the whole series annotated and dated by Rudorff in pencil, Düsseldorf (up to 1875), Lucerne, Berlin (1873-1878), Paris, Münster, Hanover, Baden-Baden, Moscow, St Petersburg, Dresden, Crefeld, Edinburgh, London, Brussels, Vienna, Rotterdam, Leipzig, Bristol, Frankfurt (from October 1878) and Interlaken, 19 December 1860 to 17 January 1896 where dated (the first letter dated by Rudorff to 1858), numbered 1-220, lacking 6 letters from May to July 1873, with typed transcripts, telegrams and letters by Marie in April 1896, reporting Clara’s heart failure and prolonged suffering and cuttings about Clara's death

2) ERNST RUDORFF'S LETTERS TO CLARA, comprising c.170 autograph letters signed and around 10 more in typescript copy only, describing music and musicians in Germany and his growing awareness of nature and environmental concerns; Rudorff praises the music of Brahms (especially the Requiem), Mozart, Weber, Mendelssohn and Schumann, convincing Clara of the need for Schumann's original and revised Davidsbündlertänze to be published in two separate editions, denigrates Wagner's music (referring to "dem giftigen Tristan" and complaining about newspaper reports of the first Bayreuth festival in 1876), criticizes Brahms for cavorting with Wagnerians like Bülow and d'Albert, reports the Berlin performance of Brahms's Second Piano Concerto under Bülow, quotes Brahms's toast to Mozart and Mendelssohn at the unveiling of a monument to Mendelssohn in 1892, discusses his own works and performances, describes concerts by Joseph and Amalie Joachim (including their performance of Brahms's "Wiegenlied" [op.91, no.2] in 1866), reports on the court proceedings in the Joachims' divorce case during 1881-1884 (persuading her nevertheless to perform in Berlin in 1883), laments Joachim's lack of self-confidence in his relations with Brahms, gives detailed descriptions of the piano-playing of Wilhelmine Clauss-Szarvady, Anton Rubinstein (comparing his playing in Cologne in 1868 unfavourably with Brahms's), Carl Tausig (comparing his performance of Kreisleriana unfavourably with Rubinstein's), Janotha, Elisabeth Schichau and Leonard Borwick, discussing the merits of Bruch, Spohr, Hiller, Stockhausen, Bülow, Nikisch, Levi, Reinecke, Wüllner, Moszkowski, Spitta, Livia Frege, Hallé and Karl Rose, the education of Clara's children, including his own teaching of Ferdinand and Eugenie, the deaths of Julie and Felix, his possible military service, the political upheavals of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, with autograph musical examples, including one page notated for two pianos (from the Variations op.1 dedicated to Clara in 1862), together with 3 letters to Clara by Rudorff's mother Betty (née Pistor) and six by his wife Gertrud (née Rietschel), 8vo, with typed transcripts annotated by Elisabeth Rudorff, mainly Berlin and Lauenstein (Lower Saxony), Leipzig, Bonn, Cologne, Wienrode (Harz mountains) and elsewhere, 18 November 1860 to 27 January 1896

THIS IS A SUBSTANTIAL UNPUBLISHED SOURCE ABOUT NINETEENTH-CENTURY GERMAN MUSIC. It contains reports of early private and public performances of Brahms’s works over four decades, reveals Clara’s views on Joseph Joachim’s acrimonious split from his wife the singer Amalie (which affected her friendship with Brahms), and expounds at length on pianos, piano-playing, her own career as a virtuoso pianist, and the frequently tragic events which afflicted her own health and that of her children. No comparable series of Clara's letters has appeared on the market since those written to Hermann Härtel (mainly about her husband’s music) were sold in Berlin in 1994. That both sides of the correspondence are present here, largely complete, makes this lot especially remarkable.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896) was a world-renowned virtuoso pianist, arguably more prominent in her field than her husband Robert. She exerted considerable influence on younger composers, especially Brahms; their relationship has been much discussed, so her reports on him are valuable. Despite her exhausting schedule of concerts and tours, she kept up a voluminous correspondence with many musical figures; indeed her expressed desire for stimulation by discussing musical matters with practical musicians who shared her outlook informs these letters throughout. The young pianist Ernst Rudorff (1840-1916), was introduced to her by her half-brother Woldemar Bargiel in July 1854, when only fourteen years of age. She gave him piano lessons and offered guidance throughout his early career. Rudorff was a skilful but conservative musician, strongly anti-Wagnerian, who served as Joseph Joachim's head of piano at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin from 1869 until 1910, whilst conducting choral societies in Cologne and Berlin (the Stern'sche-Gesangverein), and editing several volumes in the scholarly complete editions of Mozart and Chopin. Several letters document Clara and Rudorff's preparations for her appearance under his baton with the newly-formed Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra on 18 February 1883, playing Schumann's Piano Concerto and Beethoven's Choral Fantasia. She also gives the programme for a chamber "soirée", where she would have appeared with Joachim a week earlier, including Carnaval and Brahms's F major string quintet op.88.

Clara reports Brahms’s visits in 1861 and in 1863, when his A major piano quartet op.26 and the "Paganini" Variations op.35 (dedicated to Clara), were presented (“die mich immer ganz in’s Feuer bringen”); in 1865, the piano quartet again and the G major String Sextet op.36 were played; in 1870-1871, she mentions the Requiem and the Liebeslieder-Walzer op.52 (she describes the difficulties Brahms found with the singers), the Horn Trio, the Schicksalslied and Triumphlied ("...es ist gewaltig, und wirkte so, obgleich die Mittel nicht der Intention des Werkes entsprachen..."); in 1877, the premiere of the Second Symphony; in 1884, the Third Symphony and the Second Piano Concerto, and in 1888, the D minor Violin Sonata op.108, when the first three movements were each played twice, such was their reception. She repeatedly praises Brahms's late piano pieces (opp.116-119), which fascinated her and which she was able to play when other music caused her suffering:

"...Einen großen Genuß habe ich aber seit 2 Monaten, an den neuen Brahms’schen Stücken, daran sitze ich fast täglich. Welcher Schatz an Geist und Gemüth, welche Fantasie ist in diesen Stücken, welche Klangschönheiten, die ganze Art der Technik so interessant, fesselnd für Klavierspieler als Solchen. Gott sei Dank schwindet mein Leiden, wenn ich selbst spiele, beinah ganz, und so genieße ich ungetrübt kann auch Unterricht ohne Stōrung ertheilen... [16 January 1893]"

As late as February 1895, Clara attended the Brahms week in Frankfurt, when the new Clarinet Sonatas op.120 were presented, during which time Brahms played the G minor piano quartet op.25, and was persuaded (although intending only to be in the audience) to conduct his Academic Festival Overture op.82; she remarks on his electrifying conducting, his delightful playing and his pleasure at his reception, especially since he was usually criticised for his piano-playing as he got older (not least by Clara):

"...Wir haben eine genußreiche Woche durch Brahms’ Anwesenheit verlebt, seine beiden Sonaten nur lieber noch gewonnen. Sein Quartett in G moll hat er so wundervoll gespielt, daß alle Menschen entzückt über sein Spiel waren, was ihm, glaube ich, eine besondere Freude war, da er eigentlich fast immer als Clavierspieler getadelt wird. Dann hat er seine academische Ouvertüre, obgleich er dem Concert nur als Zuhörer beiwohnte, auf dringendes Zureden selbst dirigiert, und das war wahrhaft electerisierend...[21 February 1895]"

Clara reported her last meeting with Brahms in October 1895, when he spent a day at her home in Frankfurt, remarking on his singular achievement in being admired within his own lifetime. Yet she still retained her critical faculties in her last letter of 17 January 1896, denouncing as tasteless Brahms conducting Eugen d’Albert in performances of both piano concertos, "one after the other like that".

Clara was also close to Joseph Joachim (1831-1907) and his wife the contralto singer Amalie (1839-1899), frequently performing with both, as Rudorff reports. When Joachim sought to divorce Amalie in 1881 (for her supposed infidelity with Brahms's publisher Fritz Simrock), the ramifications for Clara were considerable, since she felt that she could not visit Berlin to perform with one, whilst not the other. Ultimately, her loyalty to Joachim was stronger, so her position diverged from Brahms’s, who resolutely supported Amalie. She confided her views to Rudorff here, urging him not to repeat them. For her, it would be much better for the pair to separate, and she denigrated Amalie’s continuing appearances in Gluck's Orphée and in concerts ("...NB: Können Sie denn gar nichts über Joachim vermögen? Könnte nicht ein guter Freund ihn dahin bringen, dass er sich von seiner Frau trennt? Es ist ja unmöglich, dass sie so fortleben, und er geht gewiss darüber zu Grunde!" [20 September 1881]). In turn, Rudorff reports Amalie's last-minute retraction of her claims against Joachim in early February 1881, explaining that this led Joachim not to pursue the matter, adding that he himself of course knew which side she supported. She turned more and more to Rudorff for musical discussions, gossip and advice from this time on.

Ernst Rudorff's pioneering achievements in the field of German environmental protection have arguably proved more enduring than his music. He coined the term "Heimatschutz" ("the protection of our homeland") and these letters chart his growing interest and concern for the German countryside from the outset. Although it is a minor thread in his letters to Clara, as early as 1866, he lamented the destruction of woodland near Bad Kreuznach in the Palatinate and in 1890 describes a fortnight's trek through particularly beloved haunts in his "Heimath". Later, he bought up land in the Weser-Bergland in Lower Saxony in order to save it for Germans in perpetuity. In 1904 he founded the "Bund Heimatschutz", still an important environmental protection agency in Germany (now the BHU in Bonn). There is little evidence in these letters of the anti-Semitism later attributed to him.

Although Clara's relationship with "lieber Rudorff" was never as intimate as it was with "liebster Johannes", he soon got to know her four daughters, who were of a similar age, and taught Eugenie, Ferdinand and Felix. Clara also knew Rudorff's parents, and his Jewish godmother Marie Lichtenstein (1817-1890), whilst among their circle were Brahms, Joachim, Stockhausen, Bruch and Hiller. Clara increasingly sought Rudorff's company and advice, especially when the visits from Brahms became less frequent. They met and discussed both musical issues and their family problems, and she is quite frank about her own physical decline (”dann meine Gehör, das mich keine Musik im Saale mehr genießen läßt”). It was to Rudorff that she turned for advice when Brahms planned to publish the original version of Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze op.6 in Breitkopf & Härtel's Complete Edition. Rudorff convinced her to agree to this, conceding the musical coherence of the revision whilst commending the authentically German exuberance of the original ("...daß der junge Schumann mit aller Überschwänglichkeit in voller Unverfälschtheit den Andenken der deutschen Nation erhalten bleiben soll”..."). Despite some letters missing from 1873, perhaps reflecting disagreeable events involving Nathalie Janotha and her mother, their correspondence continued until a few weeks before Clara suffered severe heart failure in March 1896 (she died on 20 May).

LITERATURE:

UNPUBLISHED. The first edition of Rudorff's incomplete memoir Aus den Tagen der Romantik (1938) only covers his first few meetings with Clara and does not quote any letters; the edition by Katja Schmidt-Wistoff (2008), takes his fragmentary narrative up to about 1873 and reinserts his discussions of Mendelssohn and other Jewish musicians. Nancy Reich quotes from a few letters in her biography Clara Schumann: the Artist and the Woman (1985), but this correspondence remains substantially unknown.

Please note: Condition 11 of the Conditions of Business for Buyers (Online Only) is not applicable to this lot.

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here