LUDWIG DEUTSCH | THE SCRIBE

Auction Closed

October 22, 05:34 PM GMT

Estimate

800,000 - 1,200,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

LUDWIG DEUTSCH

Austrian

1855-1935

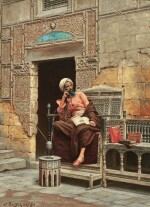

THE SCRIBE

signed, inscribed and dated L. Deutsch PARIS 1904 lower left

oil on panel

51 by 37cm., 20 by 14½in.

We are grateful to Dr Emily M. Weeks for her assistance in cataloguing this work which will be included in her critical catalogue of the artist's Egyptian and Orientalist works, currently in progress.

Mathaf Gallery, London

Purchased from the above

Sydney, The Art Gallery of New South Wales; Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Orientalism: Delacroix to Klee, 1997-98, no. 56, illustrated in the catalogue

Caroline Juler, Najd Collection of Orientalist Paintings, London, 1991, p. 45, discussed; p. 53, catalogued & illustrated, also illustrated on the cover

Possibly, Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, Veiled Images, Rotterdam, 1996, p. 9 (one of the three known compositions cited)

Possibly, Simon P. X. Battestini, African Writing and Text, trans. Henri G. J. Evans, New York, 2000, p. 285 (one of the three known compositions cited)

Todd Curtis Kontje, German Orientalisms, Ann Arbor, 2004, illustrated on the cover

This painting depicts a scribe or katib in Cairo, who is shown sitting in the street in a meditative state. Although his name is unknown, the model appears to be the same as in several of Deutsch's best known works, such as The Mandolin Player or The Philosopher (both in the Shafik Gabr Collection; see James Parry, Orientalist Lives: Western Artists in the Middle East 1830-1920, Cairo & New York, p. 161). Another version of this composition, with a different model in a similar pensive pose and dating from 1896, was formerly in the Coral Petroleum collection.

One of the traditional professions in the Middle East, public scribes earned a living by reading as well as writing. They were respected, educated individuals, in a culture which placed a high value on literacy and the subtleties of elegant calligraphy. In painting the present work, Deutsch may well have been thinking of the many depictions of scribes in Ancient Egyptian art, as much as their role in contemporary society. One example, dating from circa 2600-2350 BC and known as the scribe accroupi, was discovered in Saqqara in 1850 and entered the collection of the Louvre.

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 set an end to the Abbasid Caliphate and to what has been considered by many the ‘Islamic golden age’. A crucial moment in Islamic history, this event saw the transition of the political and cultural epicenter of the Muslim world from Baghdad to Cairo. The fear of destruction and the concentration of the scholarly elite into one sole city led to an outpouring of printed material, both sacred and secular, which had its fullest flowering in the Mamluk Empire (1250-1517): ‘The concentration within the Mamluk urban centers of scholars and literati from around the Muslim world […] was paralleled by processes of centralisation and consolidation in two other domains, namely the financial administration of the empire and the political unification of Egypt and Syria. These centralizing processes directly impacted the sociology of intellectual exchange during this period and are mirrored, I contend, by a fourth form of consolidation in the sphere of textual production.’ (Elias Ibrahim Muhanna, Encyclopaedism in the Mamluk Period: The Composition of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī’s (D. 1333) Nihāyat al-Arab fī Funūn al-Adab. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, 2012, p. 47).

By exploring the theme of literacy in Egyptian culture, Deutsch is at the same time both celebrating its glorious history and underlining its importance in both secular and religious life, at a time when modern innovations in the printing process were threatening the traditional role of professional scribes. As a painter in an age of mechanical reproduction, Deutsch may have felt sympathy for their situation.

To ensure ethnographic exactitude, Deutsch and many of his fellow Orientalist artists used Islamic tiles, furniture, textiles and metalwork as studio props. Here the scribe is seated on an east African 'Grandees' chair', an amalgam of Mamluk, Portuguese, and Indian influence. The wall behind is decorated with ornate Mamluk carvings. The same setting and props served fellow painter Paul Joanowits for his painting, Bashi-Bazouks Before A Gateway. In turn, both compositions may be derived from a photograph by Gabriel Lékégian, whose images Deutsch is known to have owned (fig. 1).