BHUPEN KHAKHAR | Two Men in Benares

Auction Closed

June 10, 01:39 PM GMT

Estimate

450,000 - 600,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

BHUPEN KHAKHAR

1934 - 2003

Two Men in Benares

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated indistinctly in Gujarati lower right

Bearing a TATE exhibition label on reverse along with another distressed label

160 x 160 cm. (63 x 63 in.)

Painted in 1982

Acquired from the artist through Chemould Gallery, Bombay, April 1986

Paris, Palais de Chaillot, Festival of India, June 1985 - 1986

London, Tate Modern, Bhupen Khakhar: You Can't Please All, 1 June - 6 November 2016

Berlin, Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Bhupen Khakhar - You Can't Please All, 18 November 2016 – 5 March 2017

T. Hyman, Bhupen Khakhar, Chemould Publications and Arts, Bombay, 1998, illustration pl. 21, p. 84

G. Kapur et al, Bhupen Khakhar, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2002, illustration, p. 14

J. Bell, Mirror of the World: A New History of Art, Thames & Hudson, 2007, illustration pl. 337, p. 448

T. Hyman, The World New Made: Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century, Thames & Hudson, London, 2016, illustration p. 224

C. Dercon and N. Raza, Bhupen Khakhar: You Can't Please All, Tate Publishing, London, 2016, illustration p. 54

‘In 1965 critics spluttered in outrage at the first exhibition of a young accountant-turned-painter from Baroda at the Jehangir Art Gallery, Bombay. "Is this madness?" fumed renowned art critic Charles Fabri. At first take the exhibits looked harmless enough: ambivalent oleographs of little divinities culled from popular calendars, pasted on mirrors, buoyed up with some gestural brushwork and graffiti. But that graffiti. Juxtaposed next to the vermilion-smeared, worship-worthy images was the legend: "It is prohibited to urinate here." Cut to 1987 (sic 1982). The painter, Bhupen Khakhar… paints the overtly homosexual Two Men in Benares. Two men stand in naked embrace, their erect penises almost touching. The face of the older man, though masked by the dark, urgent profile of the younger is recognisably Khakhar's. There's no mistaking those elephant ears, the shock of white hair as anyone else's. The image that conjoins genital excitement and a religious setting, marries the sacred with the profane, is Khakhar's ringing proclamation of his own homosexuality. Critics lash out at him for his lasciviousness. Proprietors of the Chemould Gallery, Bombay, stash away the painting in the storeroom two days after the exhibition opens in the face of protests from the Cottage Industries authorities on whose premises the gallery is located. Through 22 years, the painter had retained his ability to surprise, provoke, startle, to be artistically himself.’ (S. Mehra, ‘An Accountant Of Alternate Reality,’ Outlook India, 13 December 1995, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/an-accountant-of-alternate-reality/200402). Within his career and thereafter, Khakhar has become the one artist from India who has received the most international and highest placed institutional critical attention. He has been exhibited at illustrious venues including the Tate in London, the Centre Pompidou, Paris, the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, The Museo Nacional Centre de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. Khakhar was also the first artist of Indian origin to be selected for Documenta IX in Kassel back in 1992.

Two Men in Benares is among the three works that are unanimously considered to be the most important in Bhupen Khakhar’s oeuvre in that they were confessional paintings by way of which he announced his homosexuality to the world. It is a much published but remarkably rarely seen work. In a letter to his friend and biographer, Timothy Hyman, Khakhar wrote "Paintings like Yayati, Two Men in Benares, You Can’t Please All are efforts to come out in open.' (J. Dhar, ‘Love in the Time of Bhupen,’ Art Asia Pacific, Issue 98, May-June 2016, p. 104) ‘I started Two Men in Benares when I visited the city. This happened only after 1980, when I got some confidence in myself that I can paint." (Interview by Amit Ambalal with Bhupen Khakhar, ‘God, Truth and Coca Cola,’ Bhupen Khakhar: A Retrospective, NGMA and The Fine Art Resource, 2003, p. 114)

Born in Mumbai into a middle-class Gujarati family, Bhupen Khakhar trained as a chartered accountant, the first in his family to attain higher education. Moving to Baroda in 1962, where he chose a new career path as a writer and an artist, allowed him to break free from family pressures. Largely self-taught, Khakhar was encouraged by his friend Gulamohammed Sheikh and later became a key figure at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Baroda. The Baroda school's primary focus became figurative art with a strong emphasis on narrative. In 1976, Khakhar made his very first trip abroad facilitated by a cultural exchange programme by the Indian government which took him to USSR, Yugoslavia, Italy and the United Kingdom. In the UK, Khakhar stayed with his mentor, British artist, Sir Howard Hodgkin as his guest. In 1979, he returned to the UK, this time as an artist-in-residence at the Bath Academy of Art in Corsham. Khakhar lived with Hodgkin again, this time for six months, teaching at Bath once a week. The experience in the UK turned out to be transformative for Khakhar. In England in the 1970s, Khakhar bore witness to the increasing acceptance of homosexuality resultant of it becoming legalised the decade before. Being exposed to and interacting with artists such as David Hockney and Hodgkin himself, gave him the much-needed freedom which he had yearned for. This time also coincided with the death of his mother in 1980 which allowed him a 'new freedom of public action.' (T. Hyman, Bhupen Khakhar, Chemould Publications and Arts, Bombay and Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, 1998, p. 68) Together, these aspects facilitated what has been termed as his 'coming out of the closet' and declaring his homosexuality, something which he had hinted at, in subtle ways all his life, through his work, but never outwardly until the UK experience. This became the hallmark of the next phase in his artistic production, an autobiographical one that made him the first Indian artist to freely disclose his sexual orientation through his work.

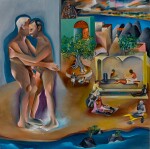

Two Men in Benares is a seminal work both for the context it was made in and its powerful and complex imagery. In equal parts it is subversive, sensual and sentimental. The canvas is divided cleverly into vertical planes – two life size nude men with erect penises embrace each other in the left third of the painting while vignettes of everyday life dominate the remaining two thirds. The vignettes include devotees in a temple tending to a shivling, a beggar and a man being massaged outside the temple, and other random figures dotting the canvas. A wall separates these two scenes set in the holy city of Benares - we see the river Ganges encircling this vista. The two men are both on the outside of this quotidian scene and within it. In the dark and on the periphery, they are not furtive but rapt and their bodies illuminated as if almost holy; they are isolated both by circumstance and by society as they partake in their own private lila or play. The older figure is autobiographical, bearing Bhupen Khakhar’s trademark white shock of hair as he gently caresses the younger man. It is telling that the title of one of Khakhar’s early 1972 exhibitions was, Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God. Khakhar was not only being starkly upfront about his yearning, he was also facing life as an aging gay man who worried about his potency. Ultimately, his art was in reaction to his illnesses and mortality. ‘Bhupen’s later paintings, which were more explicit, once again reflected his sexual preferences, featuring older men, with sagging bodies and white hair. At his house in Baroda, he had a wall full of portraits he had done of former lovers. [A Gallery of Rogues, 1993] “Most of them are dead,” he said, with the droll humor I later came to know he was famous for. “It’s hard finding older men at my age.” (D. Ganguly, ‘When Bhupen Khakhar came out, through me,’ Economic Times, 8 September 2018)

Co-curator of his Tate retrospective, Nada Raza has reflected on Khakhar’s symbolism, ‘He said that he thought of great paintings in the same way he thought about great novels, complex and layered… the delineation of public and private is something that Khakhar portrayed often, using the device of the doorway or window [a wall in the case of Two Men in Benares].' (O. Gustorf and N. Raza, ArtMag by Deutsche Bank, 2016) Whether it was the earlier trade paintings or the later autobiographical ones, Khakhar frequently created secondary spaces in his pictures with scenes of everyday life. ‘This compositional strategy broadens the interpretation of his works, for example, the vignettes in the Two Men in Benares encourage the viewer to interpret the work as a visual statement about the life experiences of homosexuals in India.’ (C. Summers, The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts, Cleis Press, 2004, P. 199) "Two Men in Benares was painted when I think I needed courage. All the time I sought courage. I think courage also had to do with my later work—during my illness—Blind Babubhai, Bullet Shot in the Stomach, Beauty is Skin Deep." (Interview by Amit Ambalal with Bhupen Khakhar, ‘God, Truth and Coca Cola,’ Bhupen Khakhar: A Retrospective, NGMA and The Fine Art Resource, 2003, p. 114)

The work also begs the question – why Benares? ‘Khakhar himself explained that, in India, there were not many places for gay people to meet, and so one would often go to the temple or masjid to make connections.’(J. Dhar, p. 105) Khakhar has painted many works with religious connotations and settings, including Yayati and Guru Jayanti. Noted art historian, Shivaji Panikkar has commented ‘The artist … moves away from the private/autobiographical to nebulous public domains such as religious practices. ….it was not religion per se that excited his imagination, but, rather, the specific play of sexuality that he perceived underlay Hindu myths, stories and icons that he constantly explored.’ (SK Panikkar, An Art Historian’s Appreciation, https://bhupenkhakharcollection.com/essay/). Here he employs and adapts the colours and tropes of the Ragamala, the Gita Govinda and the imagery of Krishna as Shrinathji.

Speaking of the present work, art critic, Jyoti Dhar notes, ‘It certainly seems the case that pleasure and love were of utmost importance to Khakhar, both in the way he led his life and in the way he painted. One could say, with the way he is said to have caressed his canvases as he worked, loosely applying colour and taking the time to depict every detail of the body with care, that painting itself was a sensual act for him. Two Men in Benares does seem indicative of both duration and generosity in the way it lovingly portrays many perspectives at the same time: from the simultaneous privileging and normalizing of the sexual act, to drawing parallels between human desire and godly worship. (J. Dhar, p. 105) There are other additional clues imbedded in this work – some more obvious than others. Bhupen was known to have had older partners in his personal life as we see here. There are no women in this composition. The shivling in the temple is also a symbol of the lingam - the male generative organ, phallus.

A number of influences are at play on Khakhar's canvas. The ordinary men in this work recall the manner of 18th century Company School paintings wherein artists recorded customs and views of an exotic land for European patrons in a documentary fashion. We also see an influence of Indian miniatures in colour and design. The multiple narrative episodes across a single picture plane was inspired by Italian Renaissance painting and most notably the work of the 14th century painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Khakhar was particularly enamoured by Lorenzetti's fresco, The Well Governed City (1338), which he saw on his first visit to Europe in 1970s. Using the background (in this case Benares with the Ganga on the foothills of the Himalayas) as a foil for the central subject is an age-old Sienese convention, as seen in the art of Duccio de Buoninsegna, Simone Martini as well as the Lorenzetti Brothers. Khakhar presents his audiences with different vantage points, indigenous as well as international, by way of which they can enter the work and identify with it.

Speaking of his subjects, he has elaborated, “…every evening after five, I walk through the Bazaars and I make a mental note whether I am going to use this shop or that in the next painting I am trying to evolve. I am at a loss to know exactly what my feelings are towards these people. At one time I feel fully sympathetic towards these people; but at other times I also feel against their hypocrisy. And another thing is that I come from that same class. So I feel some kind of immediate identification with them. So it goes on at so many levels. I attack it and I love it, don’t know what it is…” (U. Beier and B. Khakhar, Courtesy Aspect Magazine, Issue no. 23, January 1982, unpaginated) The duality of Bhupen’s life and career – as an artist and an accountant – aided his image making and his ability to penetrate and depict the life of the common man. What was also beneficial was that his lifestyle broke all barriers of religion, class and caste. While at first glance, this work appears social, there is a baffling sense of loneliness in it too, a play of empathy and mockery depicted by a man who sees himself as both a witness and an accomplice.

At his Tate Modern Retrospective in 2016, the current lot was exhibited in a special section titled ‘My Dear Friend’ with others from this period including Yayati. In the didactics of the exhibition, the curators reflected on Khakhar’s themes of intimacy and devotion, ‘He was interested in mystical Bhakti spiritual traditions, which often expressed the idea of love between men, master and disciple, as a form of devotion’ (Bhupen Khakhar Room Guide, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/bhupen-khakhar/room-guide/bhupen-khakhar-room-four) In this regard Bhupen is different from David Hockney with whom he is often compared. Both artists were gay and explored the nature of gay love in their art. ‘His [Hockney’s] concern was with men alone, Khakhar's concern seems to be as much the men as the metaphysics of their condition. "Hockney is concerned with physical beauty. I am much more concerned with other aspects like warmth, pity, vulnerability, touch...", he once said.’ (S. Mehra, ‘An Accountant Of Alternate Reality,’ Outlook India, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/an-accountant-of-alternate-reality/200402)

Khakhar’s eccentric works are surely the result of an artist doing exactly what he liked, depicting the mundane with the imaginary and the intriguing, the sacred with the profane, making use of a variety of sources in an unabashed way to weave an idiom, unambiguously his own. ‘Through the innumerable changes of oeuvres between those first collages and the present "confessionals"; through the various avatars as collagist, neo-miniaturist in the '60s, diarist of the demeaned in the '70s, painter of the narrative in the '80s, gay icon of the '90s; through all the aspersion, appreciation, rejection, acceptance, pannings, panegyrics, Khakhar…has remained unapologetic.’ (ibid.)

In life truth and honesty are suppressed. I represent Truth. My slogan is: Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God. I want to reach beauty by truth alone. It is a difficult road. many temptations may be offered to me by devils. I will not succumb. It is said in Sanskrit “Satyam Shivam Sundaram." Bhupen Khakhar, exhibition catalogue, Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God, Chemould Art Gallery, 1972