T he philanthropist, banker and politician, Sir John Smith met his future wife, Christian Carnegy, at Oxford, in the late 1940s. He was reading History; she was reading English. This combination of intellects, one fascinated by the past, the other absorbed in the poetic, would create one of the great success stories in British philanthropy and – as detailed in these pages – shape a distinctly personal collection.

When Sir John and Christian founded The Landmark Trust in 1965 it was the culmination of their approach to conservation. Previously they had seen important vernacular buildings slipping through the preservation net. While heritage organisations were defending the grand country houses, the Smiths recognised that little was being done for the historically and architecturally significant but less appreciated buildings of Britain.

The Trust set about purchasing such buildings and after a programme of research and restoration let them pay for themselves as holiday boltholes. Landmark today manages some two hundred properties ranging from eccentricities such as a Grade II listed pigsty in Yorkshire and a pineapple-inspired folly in Scotland to sites of immense importance, including Pugin’s neo-Gothic house in Ramsgate and the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel.

“We have no favourite period or style,” Smith noted, “Although we lean towards the functional.” In the possessions of Sir John and Lady Smith we can see the flashes of everyday gems. Witness the naïve charm of a pair of 18th century slipware dishes, a Victorian excursion captured in George Leslie’s Thames-side Conversation and a domed model of the knapped-flint church on their estate.

Sir John and Lady Smith considered the Trust and their collection to be joint endeavours and, over the course of half a century, the couple were vital to the preservation of vernacular architecture, not just in Britain but in Europe and America too. In the process they provided cherished memories for the huge number of people who have stayed in the Trust’s properties.

John Smith was born in 1923, scion of one of Britain’s oldest banking families (founded in the mid-17th century, Smiths Bank remained independent until the early 20th century). He grew up at Ashfold, an Edwardian country house that his father had almost halved in size. John later observed that “buildings are seldom improved by additions but very often by subtraction”.

On leaving Eton, John served in the Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War, seeing action in the Mediterranean, Pacific and Norwegian theatres. He took part in the fabled sinking of the German battleship Tirpitz in the Kvaenangen fjord.

Meanwhile, Christian Carnegy grew up on the family estate near Dundee in Angus. It was a childhood of imaginative theatricals, skating and parties in historic castles. As with the Smiths, a passion for public service was part of the Carnegys’ constitution. Christian’s father won a DSO and an MC during the First World War. Her older sister Elizabeth became a leading figure in the Girl Guide movement and a respected Conservative peer. Her aunt, Dame Beryl Oliver, was decorated for her services to the Red Cross.

John and Christian married in 1952. Reluctantly giving up the idea of becoming an architect, John joined Coutts Bank and combined his successful career in finance with a series of philanthropic and heritage pursuits, for which he was recognised with a knighthood in 1988 and subsequently was made Companion of Honour. Their country house, Shottesbrooke Park, was left to John by his cousin, Nancy Oswald Smith. The house had been inherited from a branch of the family – the Vansittarts – who originated in Danzig (now Gdansk) and settled in Britain.

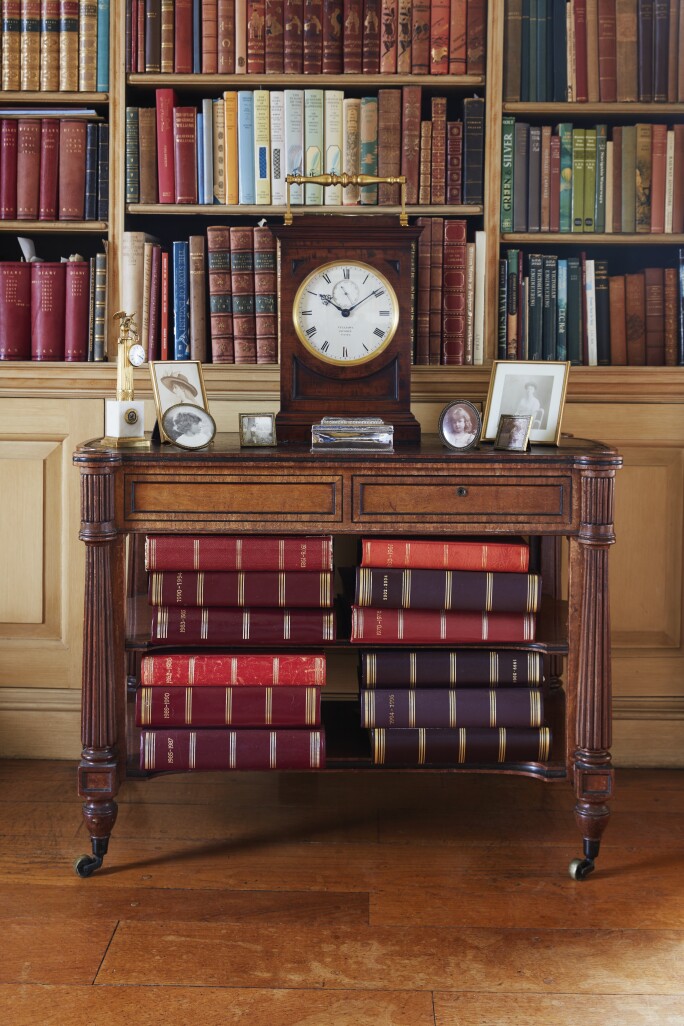

In Shottesbrooke and their Westminster residence, No 1 Smith Square, Sir John and Lady Smith created homes which displayed elements of the past and present. The result is a fascinating inherited collection that has been further enriched by the couple’s contributions.

There are striking portraits of Smiths and Vansittarts and signs of time spent abroad by various members of the family. But the overwhelming feel is that of a very British country house, albeit one punctuated by pops of colour, courtesy of Impressionist works by Marquet and Matisse and items such as a striking Italian albarello lamp. A love of colour can also be found in the items of couture and the textiles, an area beloved of Lady Smith. Her own hand-blocked materials feature in many of the Landmark buildings.

The industrial landscape of Britain is, of course, a notable presence. In their paintings and prints we find the collieries of Durham and the pioneers of locomotion. Elsewhere, a set of marine prints and oils reflect a concern close to Sir John’s heart: the safeguarding of our maritime heritage. This led to his involvement with the restoration of HMS Warrior, SS Great Britain and HMS Belfast, as well as the conservation of the nation’s canal system.

And the collection displays markers of everyday life in the country, elements of the pastoral cycle of work, rest and play: there are Grand Tour sketchbooks; Scottish plaid-design carpet bowls; walking canes with unusual terminals, some shaped like fox and rabbit heads. An affinity for rural calm can also be found in Laura Knight’s The Picnic, a bucolic scene in Cornwall, one of the highlights of the pictures.

There are, perhaps, two pieces which particularly reflect the characters of their owners. The first is LS Lowry’s study of David Lloyd-George’s birthplace in Manchester. In 1958, shortly after the painting’s completion, Sir John spotted it in the window of the Lefevre Gallery in Mayfair.

The view of the Liberal Prime Minister’s simple corner-terrace house is a quiet exercise in geometry, but it encapsulates the Smiths’ love of idiosyncratic architecture with incidental interest. Endearingly, it was the scene’s similarity to their corner of Smith Square which caught Sir John’s eye that day as he walked along Bruton Street.

And the use of their Anglo-Indian ivory and rosewood desk epitomises how purpose and beauty can be combined: Lady Smith used this fine piece as her dressing table. Here is beauty married to utility. These pieces of furniture, objects and pictures display a keen love of purpose. It is apt, therefore, that they will continue to be valued by other collectors.