T he present Dining Table is finely described in the December 1950 issue of House & Garden: “Like a fantastic skeleton, the natural maple struts of this table appear through its glass top.” There is no doubt that at first glance what strikes us is its fossil shape, like that of a strange prehistoric creature. Mollino achieved this effect of something "primitive" with industrial materials such as plywood, brass rods, tempered glass and exquisitely modernist details such as the brass guards of the table’s feet to which the tie rods are bolted. He openly displayed a construction we could describe as being brutalist (or "frankness," as it was referred to in House & Garden) yet this quality in front of our eyes "disappears" behind lines and forms.

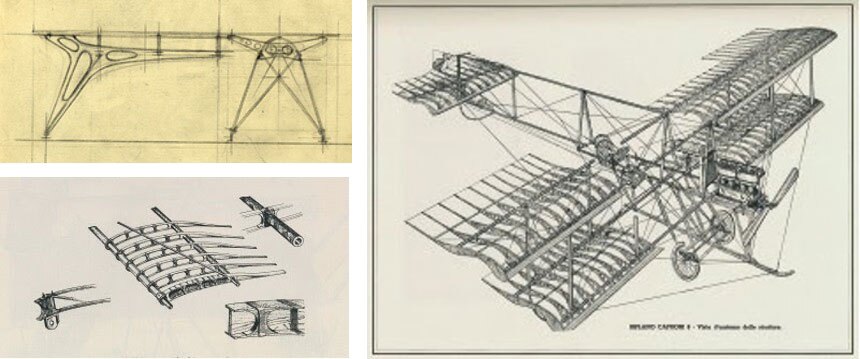

The engineering of the table is rational: the manipulated, curved form of the plywood is maintained by the brass tie rods and solid maple ribs that also act as support struts for the glass top. The table is an articulated and hybrid device easy to produce and assemble. Knowing Mollino's passion for airplanes and flight the table recalls the structure of the first airplanes. The maple ribs (which are each differently shaped) reflect in an organic way the structural weave of the wings, their curvature and also their perforation (present in the legs of the table as well) that work at the same time as a method of lightening and strengthening of the structure.

Below left and right: Early airplane design drawings. Courtesy of Museo Casa Mollino.

Mollino intended to create fantastic “machine-animals,” like those of Leonardo da Vinci, in search of a "lyrical functionalism." "Tension, not gratuitous decorative modeling," he noted in the margin of a letter, would result in the light, minimalist components of the table. Like da Vinci, Mollino was an eclectic who loved to synthesize purely technical engineering with poetic artistry, and Mollino too researched and found in nature the most sublime examples of beauty fused with functional efficacy. This led to an absolutely unique work in design history, modern and not.

In the years following 1944, we can observe in Mollino's work the constant evolution of this same idea beginning with his more sculptural, deeply excavated furniture towards a progressive linear simplification and the highlighting of the structure. In 1950 the dining table, chair and coffee table made for Italy at Work were the pivotal step towards the last phase of his design, which was concluded later that year with the furniture for Lattes Publishing House made with a single continuous plywood sheet only. Then in 1953, Mollino considered his design research exhausted and ultimately stopped designing furniture. Gio Ponti well understood the importance of these plywood furniture forms that Mollino himself defined as "total arabesques":

“Dear Mollino,

Some people, even highly intelligent people, when they see your pieces of furniture with curved surfaces stop at their 'vertebral' aspect and express an abstract opinion about them, dictated by likes or dislikes of just forms and shapes, and they do not understand the extreme importance and innovation of them being 'all structure' obtained by bending and re-bending a surface with the insertion of certain links in this unity.” 31 July 1952