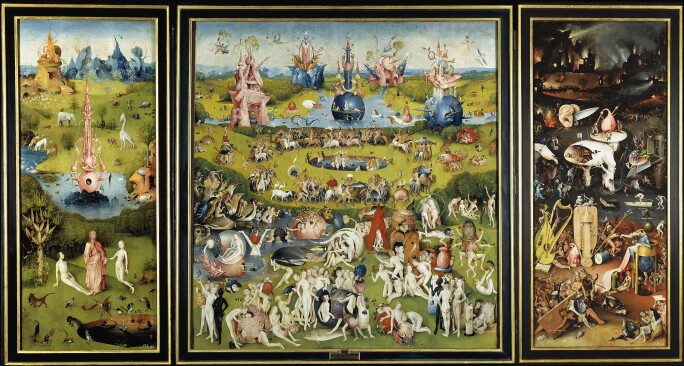

A spellbinding triptych whose nightmarish details recall the modern Surrealist movement, Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” has captivated viewers since its creation, circa 1490–1510.

A

cross three mighty panels, Hieronymus Bosch’s raucous and confounding scene of heaven and hell continues to provoke debate, influence popular culture and attract millions of visitors to the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, its home since 1933. The oak-panel triptych features a large center scene flanked by two smaller hinged-panels that, when closed, display the formation of the earth on the third day as according to the biblical creation story. When opened, the left wing depicts God's presentation of Eve to Adam in a utopic Garden of Eden, amidst a menagerie of animals.

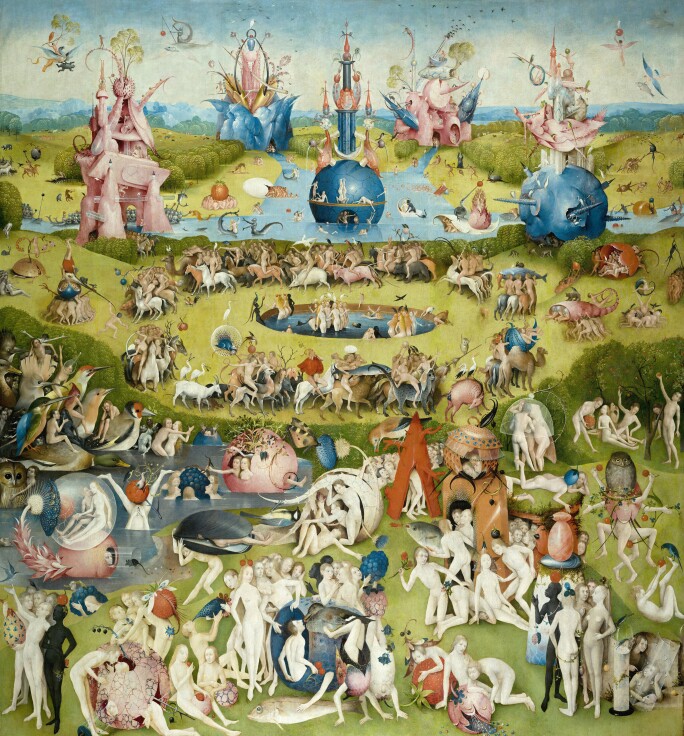

But God is conspicuously absent from the center panel, which teems with a bacchanal of cavorting nude humans enjoying a paradise poisoned by lust. This is the garden of earthly delights from which the painting takes it name. Here, real and fantastical creatures mingle with people in a dense, nonsensical landscape of bizarre vignettes and otherworldly architecture. Look closely: a fish walks on land, a man carries giant strawberries, mermaids inhabit the waters, and men ride unicorns.

In contrast, the chilling right panel gives way to a tormented hellscape – an apocalyptic scene of torture and destruction that proved a common setting for many of Bosch’s paintings. In this nocturnal inferno, a prison-like city burns while surreal creatures dole out death and punishment. A rabbit carries away a bleeding corpse, a giant ear marches forth pierced by a knife, a part-bird creature, seated on a latrine, ingests and excretes victims, men are tossed into fire, while others are poked, prodded or fed upon by their would-be executioners. At the center of this destruction is the “Tree-Man,” a surreal figure formed of decaying trunks and a cracked egg who some believe is a self-portrait of Bosch himself – a subject of much debate and impossible to verify.

In popular culture, references to the painting are manifold. Writers used “Boschian” or “Bosch-like” to evoke the artist’s surreal and chaotic nightmare. Tattoo artists replicate versions of its likeness onto skin. It’s been made into piñatas, reimagined into a Gucci fashion campaign, transformed into a 3D computer simulation, and parodied on The Simpsons. More than 500 years later, this surreal vision still awes even the most contemporary eyes.

Despite the popularity of the painting, little is known of its creator, who was born Jheronimus van Aken into a family of painters in the northern Flemish city of 's-Hertogenbosch, one of four bustling Dutch capitals. A membership to the Brotherhood of Our Lady, a local religious confraternity, brought the painter in contact with society’s elite – aristocrats, heads of state, and other nobility who later commissioned paintings from the master. If Bosch traveled in his lifetime, no record of it survives, and scholars have little reason to believe he ever moved from his house on the north side of the city square. Bosch died in his sixties, childless, during an outbreak of the plague in 1516.

Bosch rarely signed his works, and almost never dated them, and like The Garden of Earthly Delights, most of the artist’s few surviving paintings are housed in the permanent collections of museums. Sotheby’s has been fortunate to sell works by Bosch’s principal followers and other 'Bosch-revivalists' – artists working around 1550–80 who emulated the “Boschian” style that was very much in demand. Noted among these is The Temptation of Saint Anthony a circa 1550 painting that belonged to Pope Urban VIII before it joined the illustrious Barberini collection. This splendid example by a follower of Bosch, which depicts the titular saint struggling in a demonic landscape, more than doubled its high estimate when it achieved $850,000 at Sotheby’s Master Painting’s Evening sale in January 2016.

A jewel of the Prado’s collection, The Garden of Earthly Delights had been with the museum since 1933, when it was sent from the Escorial monastery for restoration. In 1936 it was put on loan for safekeeping. A world-class institution and one of the most-visited museums in the world, the Prado has one of the finest collection of European art from the 12th to 20th centuries, as well as the largest and most impressive array of Bosch paintings in existence. A feat made all the more impressive given the few works known today. Other paintings and drawings can be found in just 26 museums and private collections, some of which include the Palazzo Ducale, the Groeningemuseum, Palazzo Gimani, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. To mark the 500th anniversary of his death in 2016, the Prado and Het Noordbrabants Museum in the artist’s hometown hosted comprehensive exhibitions on Bosch. The Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP), launched in 2010, is a collaborative project of scientific research and restoration to create a new catalogue raisonné.