F rom 19-26 July, Sotheby’s presents Japan: Art and Its Essence. The single owner sale of Property from an Important Private Collection commences with a Muromachi period Shigaraki jar and a Momoyama period Bizen ware deep dish. Deeply tied to the ceramic production and aesthetics of these periods, the sale includes stoneware vessels of contemporary potters Hosokawa Morihiro and father and sons Tsujimura Shiro, Yui and Kai. Further fired works such as Taizo Kuroda’s Daizara and Ogawa Machiko’s Superlunary display highly avant-garde forms in their porcelain pieces. Subsequent pieces comprise of the red kanshitsu lacquer Orga, Vermillion by Tanaka Nobuyuki and the dyed textiles of Fukumoto Shihoko, which are followed by a group of contemporary paintings and works on paper. The sale concludes with photographic works from Takamatsu Jiro, Kitano Ken and Hara Hisaji.

Auction Highlights

Completing the Incomplete

Dr Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere

Research Director, Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures

"True Beauty could be discovered only by one who mentally complete the incomplete." - Okakura Kakuzoô, The Book of Tea

The best works of art made in Japan invite the viewer to complete or add to the viewing experience. The creative approach to art and craft formation includes not just the artist’s intentions but the machinery of manufacturing be that a kiln or a camera—as an active and occasionally visible part of the production process. This lens towards materiality and creation applies to works dating from prehistory to the present day.

The art of Japan at its very essence is performative and involves some form of subtle engagement between the object, place or space and participant. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the practice of tea or chanoyû. Okakura Kakuzô (1863-1913) in his magisterial meditation on the topic, The Book of Tea, beautifully summarises the Japanese concept of beauty as active engagement.

The initial seeming disparity of the works brought together in Japan: Art and its Essence, is upon reflection and with help from Okakura and tea practice coalesce, a rumination on history, location, process, and function. Hosokawa Morihiro’s (b.1938) powerful Large Iga Storage Jar is a masterclass on capturing an early Edo period (1615-1868) jar from the kilns in Mie prefecture, close to Shigaraki. Indeed, an impressive prototype for Hosokawa’s jar can be seen in the 15th-century Shigaraki Ware Storage Jar included in the sale.

This style of yakishime, high fire unglazed stoneware is a specialty of (but not limited to) Shigaraki, Iga, and Bizen (Imbe) kilns. Often seen in yakishime wares are marks or deformations formed during the long firing process. In more recent times other styles of kilns are used and these accidental marks can now to some extent be controlled. But notably, these marks refer directly to the process of creation and have become a key signifier for wares such as Shigaraki and Bizen. The fire marks (hidasuki) in the Bizen Ware Deep Dish from the Momoyama period (1573-1615) most likely was intentional and adds a dynamic coloration to the vessel’s surface.

Hosokawa’s jar has a large rupture in the lower third of the jar rendering it not functional for storage. The cracks appear as if something inside the jar was trying to burst free. The violence on the lower third contrast starkly with the calm perfection of the upper body of the vessel. Clearly Hosokawa knew what he was doing in creating this clean and aesthetically pleasing rupture. The work is a brilliant piece of modern art that interfaces with history (ancient kilns), process (fire power) and modernity (functional/ nonfunctional).

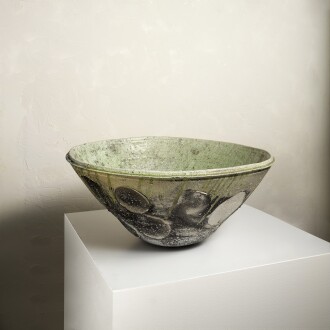

Tsujimura Shiro (b. 1947), the famous artist/ potter residing in Nara Prefecture and his two sons Yui (b. 1975) and Kai (b. 1976) also engage with creation, freely employing past idioms, the yakishime technique and working with the interface of surface and form modified by fire. Intriguingly each has their own style, but the general artistic direction was blazed by the father (Shiro). Indeed, Hosokawa apprenticed with Shiro before he set up his own kiln and Shiro’s influence is visible in his work. Shiro’s impressive large Iga Ware Bowl undulates with the natural ash glaze carefully channeled neatly on the interior pooling at the centre. Three circles appear on the rim, traces of vessels having been placed on top during the firing process. Shiro has captured the firing process and immortalised it in his finished work, thereby completing the incomplete. Yui’s large stoneware bowl, again with three circles from vessels placed on it towards the interior’s centre, resonates with his father’s work but is also quite distinct.

Yui works in the Sue ware (Sueki) tradition, a blue-grey stoneware that originated in China and Korea and entered Japan from southern Korea during the 5-6th centuries (Kofun era). This high-tech ware, fired at 1000 degrees Centigrade in a reduction atmosphere (oxygen starved) kiln was unglazed though often had natural ash glaze formation (greenish blue) on exposed surfaces. These vessels in Japan were originally employed for elite funerary implements and roof tiles but gradually came to be used for daily usage. Yui’s ceramics capture the historical essence of Sue ware but with a modern interpretation. Kai’s work reflects different traditional kilns, clays and styles but in a language all his own, such as the faceted flower vase that employs slab construction.

Kuroda Taizo (1946-2021) with his playful forms that trick the eye is another example of marrying historical references with modern sensibilities. Korean Joseon porcelain wares were his original inspiration; however, he has left his crisply formed wares unglazed, and they appear architectonic and thoroughly modern. Michikawa Shozo (b.1953) and Ogawa Machiko (b. 1946) both hailing from Hokkaido, also create thoroughly modern sculptural work. Michikawa’s work is functional, and Ogawa’s work focusses on the materiality of clay occasionally likening it to geological formations and processes.

Other artworks included in this collection reflect traditional Japanese materials such as the urushi red lacquer (Tanaka Nobuyuki, b. 1959) and an aizome indigo blue dyed Noh Robe and aizome gradation panels (Fukumoto Shihoko, b. 1945) that paradoxically feel much like contemporary art and yet are deeply historically rooted both in form and technique.

Frozen time with staged tableaux executed in a meticulous fashion are a selection of photographs created by Hisaji Hara (b. 1964). This collection showcases several works from his After Balthus series. Hara consciously references Balthus, a French Polish artist who had a considerable impact on the Japanese art world, and whose works initially serve as a template for him. But then Hara shifts the discourse to Japan and creates the tableaux in a disused medical practice. Not content with just recontextualizing the images to Japan, he creates a film set-like stills in black and white employing multiple exposures while shifting the focus on a large format camera.

Hara has succeeded in giving new meaning to his images while honoring Balthus, incorporating the past, through his camera equipment and handmade stage settings to a nostalgia tinted nod to post war Japan. Hara as completed the incomplete and by doing so has created something new, leaving us with multiple paths to interpret his work.

Okakura concludes his is chapter on ‘Art Appreciation’ in The Book of Tea to state: ‘The art of to-day is that which really belongs to us: it is our on reflection.’ The works here in this collection show how there still is a vital and vibrant dialogue with the past in the present, and we ignore it at our peril.

About the Author

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, PH.D., is the founding Director and currently the Research Director of the Sainsbury Institute and Professor of Japanese Art and Culture at the University of East Anglia, Norwich. She received her PhD from Harvard University in 1998. She published Vessels of Influence: China and the Birth of Porcelain in Medieval and Modern Japan with Bloomsbury Academic in 2012 and translated Professor Tsuji Nobuo’s A History of Art in Japan with Tokyo University Press in 2018. She was until recently the IFAC Handa Curator of Japanese Art at the Department of Asia, British Museum, and was the lead curator for the Crafting Beauty in Modern Japan exhibition in 2007 and the Citi Exhibition Manga held in the Sainsbury Exhibition Galleries, British Museum in 2019.

Linking Past and Present: Japanese Contemporary Ceramics

Beyond the Brush: Contemporary Japanese Painting and Works on Paper

Lots 23-28, include a group of contempary Japanese paintings and works on paper that challenge the boundary between painting, object and sculpture. The hand-polished urethane-coated MDF panels of Saga Atsushi’s works inside (001) and inside (002) appear almost like mirrors with their glossy, reflective surfaces.

In Wada Reijiro’s VANITAS, the artist draws from the subject of memento mori popular among seventeenth century Dutch and Flemish artists.

The brass panels forming a polyptych arrangement are splattered at high velocity with fruit – these remain there until they naturally decompose and leave behind a worn patina where the brass surface has eroded in the trajectory of the thrown fruit acid.

Works on paper include Haraguchi Nobuyuki’s Loess, No. 11 and Loess, No. 12 and Takmatsu Jiro’s Shadow Portrait of a Mother and Child. The first in rubber and pastel, industrial materials central Haraguchi's work. Takamatsu’s portrait reflects on the notion of absence vital to his Shadow series.

In Honda Takeshi’s large scale Mountain Life – Shoji, a modicum of light gently filters through the paper shoji, yet we are in an immensely dark room of a rustic mountain abode. The paper is worn and broken in places revealing further pools of darkness from the outside. Through the accretion of charcoal, Honda Takeshi creates an intense variety of shades in this monumental, monochromatic work.

Honda’s process involves the use of black and white photographs as a basis for his charcoal drawings. After photographing his subject, Honda draws fine lines over it as it were graph paper. A magnified version of this stencil is pasted onto a panel that he will complete his final drawing, painstakingly depicting each square from the photograph and meticulously matching it onto the enlarged grid. His process at times takes several months to a year to complete.

Read Less